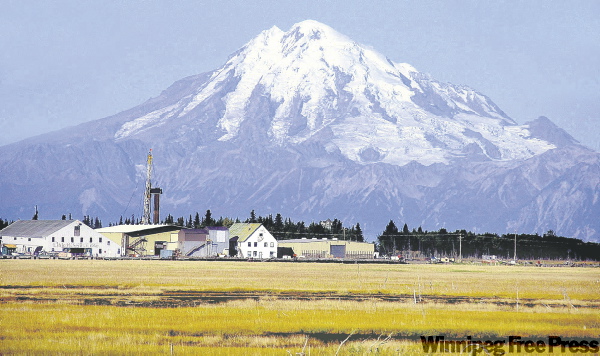

Refinery in shadow of erupting volcano

A bad environmental decision 40 years ago has Alaska in a quandary

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/05/2009 (6062 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

ANCHORAGE, Alaska — When Mount Redoubt began erupting in March, the nearby Drift River oil terminal suddenly emerged from the obscurity of a low-key industrial facility to the potential source of an environmental disaster on the scale of the Exxon Valdez.

And with its place in the spotlight came an obvious question: How could such a hazardous facility have been built there, just 22 miles — 35 kilometres — from Redoubt’s cone?

"That is the most consistent question I hear on the street," said Bob Shavelson, executive director of the environmental watchdog group Cook Inletkeeper. "The everyday, walkingaround person scratches their head when they hear there’s an oil terminal at the base of an active volcano."

The precise details of why it’s there are lost in the haze of history. The current owners, Chevron-managed Cook Inlet Pipe Line Co., say they inherited the facility in 2005 when Chevron bought out Unocal, the prior operator, and don’t know its full history. State records show that officials from Mobil, one of Cook Inlet Pipe Line’s original owners, initiated the purchase and lease of two state land parcels for the terminal in early 1966. A workaday storage and transit facility for crude oil, tiny by comparison with industrial monsters like the Valdez terminal and accessible only by air or boat, Drift River usually operates with routine monotony. The oil comes in from platforms in Cook Inlet. The oil goes out in the hulls of tankers.

State records show it received its first permits in 1966 and was licensed to operate in 1967, but there’s no record of a public discussion of the facility. The state file of its 55-year tidelands lease to Cook Inlet Pipe Line has not a single word justifying the use of that particular site. The modern environmental movement was just dawning then, and it would be three years before president Richard Nixon would sign the National Environmental Policy Act with its requirement for a detailed impact statement — including alternatives — on projects like Drift River.

Kevin Banks, director of the state’s Oil & Gas Division, said the question of why the oil terminal was built at the foot of an active volcano has been the talk of his office too. While the risks are now obvious, it’s easy to see the advantages of Drift River, he said. The land there is flat, the beach heads straight into the inlet, then drops off. The Christy Lee platform, a loading dock a mile offshore in deep water, connects to the terminal by pipeline.

"You have to go miles (offshore) before it drops off — everywhere except at Drift River," Banks said.

Walt Parker, a retired state transportation and oil official, said Drift River "was the first place they could get reasonable size tankers into" going south from the oil fields.

John Norman, a member of the Alaska Oil & Gas Conservation Commission with long involvement in the industry as an attorney, said that in the 1960s the state was so hungry for economic development that it sometimes accepted projects without question.

State land records show Cook Inlet Pipe Line bought 898 acres for the terminal for $36,000 on April 26, 1966. A separate lease governing 392 acres of adjacent tidelands for access and pipelines initially cost the company $500 a year when it was signed June 13, 1966. The current annual rent is $5,750. The lease expires in 2021.

At the time of its charter in 1966, the Cook Inlet Pipe Line was owned by Mobil, Unocal, Marathon and Atlantic Richfield.

Larry Smith, a long-term Homer activist who served on the federally chartered Cook Inlet Regional Citizens Advisory Committee when it was founded after the Exxon Valdez spill, said the Drift River terminal completely escaped his notice when it was built.

"There weren’t any questions about it," he said.

Now that the terminal is in place and the Cook Inlet oil fields are in decline, it would be uneconomical to relocate the facility, said Santana Gonzalez, a spokesman for Cook Inlet Pipe Line Co.

"Several options are being studied but we cannot get into that at this time," he said in an e-mail message.

Petty Officer Sara Francis, spokeswoman for the Coast Guard, one of the facility’s regulators, said the owners are considering a workaround that would keep it open but would dismantle the current tanks. In their place would be a new tank and pumping system that could empty the tanks quickly in an emergency, she said.

Now, the pump intakes are above the bottom of the tanks and there’s no easy way to drain them dry.

When the Cook Inlet fields were in their prime in the 1970s, tankers would call at Christy Lee every other day. They’d sometimes be backed up in the lower Inlet for a chance to load. With production outstripping the capacity of local refineries, they’d frequently haul their cargo to the Lower 48 and sometimes to Asia.

Now a tanker arrives about once a month and delivers the oil a few miles away at Nikiski, where it accounts for about one-fourth of the crude refined there by Tesoro.

Or did.

Since March 23, when workers hastily retreated as a gush of cementlike mud and water boiled down from Redoubt’s flanks, Drift River oil terminal has ceased normal operations.

Francis, the Coast Guard spokeswoman, said it could be months before Drift River reopens.

And Redoubt is still capable of exploding unpredictably over the next months.

"They’re not focusing on moving oil," Francis said. "They’re focusing on removing the (stored oil) while it continues to be in the shadow of an erupting volcano."

That Redoubt is an active volcano should come as no surprise to anyone paying attention. Capt. James Cook, for whom the Inlet is named, noticed "white smoke but no fire" coming from Redoubt in 1778. Over the course of written history, geologists say it is the second-most active of Cook Inlet’s four active volcanoes.

Redoubt exploded at 9:47 a.m. on Dec. 14, 1989. It exploded 22 more times until it began to quiet in late April 1990.

More than 37 million gallons of crude was in storage at Drift River tim at the time — three times the amount of oil spilled from the tanker Exxon Valdez in early 1989. The Drift River shifted from one channel and into another, demonstrating how unpredictable it can be. Mudflows inundated the tank farm, but the tanks didn’t leak.

The terminal closed and oil production halted in Cook Inlet. In response, Cook Inlet Pipe Line Co. built a concrete- armored dike around the facility. Construction of the nearly two-mile wall began April 9, 1990, and concluded that August.

When Redoubt, with its thenuntested dike, began to rumble in January, scientists at the Alaska Volcano Observatory warned an eruption was possible. Shavelson, of Cook Inletkeeper, asked Cook Inlet Pipe Line, the Coast Guard and the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation for a report on the amount of oil stored. That number would tell whether nearby clean-up equipment was up to the task, he said.

He was told the information was a homeland security secret. Reporters got the same response.

Shavelson said he suspected the company just didn’t want to reveal the risks to the public. It wasn’t until the eruption started and the facility was abandoned out of fears for worker safety that Cook Inlet Pipe Line disclosed the tanks held 6.2 million gallons.

There’s evidence to support Shavelson’s suspicion that the company’s concern about disclosure wasn’t out of fear of terrorist attack. Despite the dangerous levels of oil in its tanks, the facility didn’t have a single closed-circuit camera to monitor what was happening after the workers left. Francis, the coast guard spokeswoman, said cameras were finally installed two weeks ago.

— Anchorage Daily News