Dismantling otherness

History of racism in Quebec education system explores construction of racial hierarchies

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/01/2024 (655 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Growing up in rural Quebec, this reviewer recalls Social Studies projects which involved poring over strange library cards which described both Algonquin and Iroquois “daily life” through hand-sketched drawings of what the artists perceived as social, cultural, political and anatomical accuracies.

Indigenous people, for this reviewer, were portrayed as something of the past, created out of the imagination of a textbook company — and influenced by hundreds of years of stereotypes and layers of racism.

Forty years later, questions persist: who is able to create their own history? How is one’s history silenced? What role has public education played — and still plays — in the othering and silencing of Indigenous peoples in both the past and present?

Adèle L’Heureux-Hubert

Catherine Larochelle

Quebec historian Catherine Larochelle has similar questions in her deep inquiry into the history of racism within Quebec education. In School of Racism: A Canadian History, 1830-1915, Larochelle, professor of history at the University of Montreal, began to notice the type of school work and representation of Indigenous peoples her daughter was bringing home. What resulted was a deep dive into Quebec textbooks, educational journals and a thorough theoretical framework that would become her dissertation and this book.

Originally written in French and translated by S.E. Stuart, Larochelle establishes the notion of alterity — that is, the process of otherness, or othering. “When the relation to the Other is reduced to his representation as a figure known through observation, a relation of imaginary and material domination is established,” she argues. Through the lens of European imperialism, the otherness of the body, physical images of racialized people, a trend in saving the at-risk child and a specific examination of Quebec’s othering of Indigenous peoples, Larochelle reveals that schools and schooling are “not only one of the first sites of ‘literacy’ regarding otherness but is in addition one of the only ones that can claim authority of the state.”

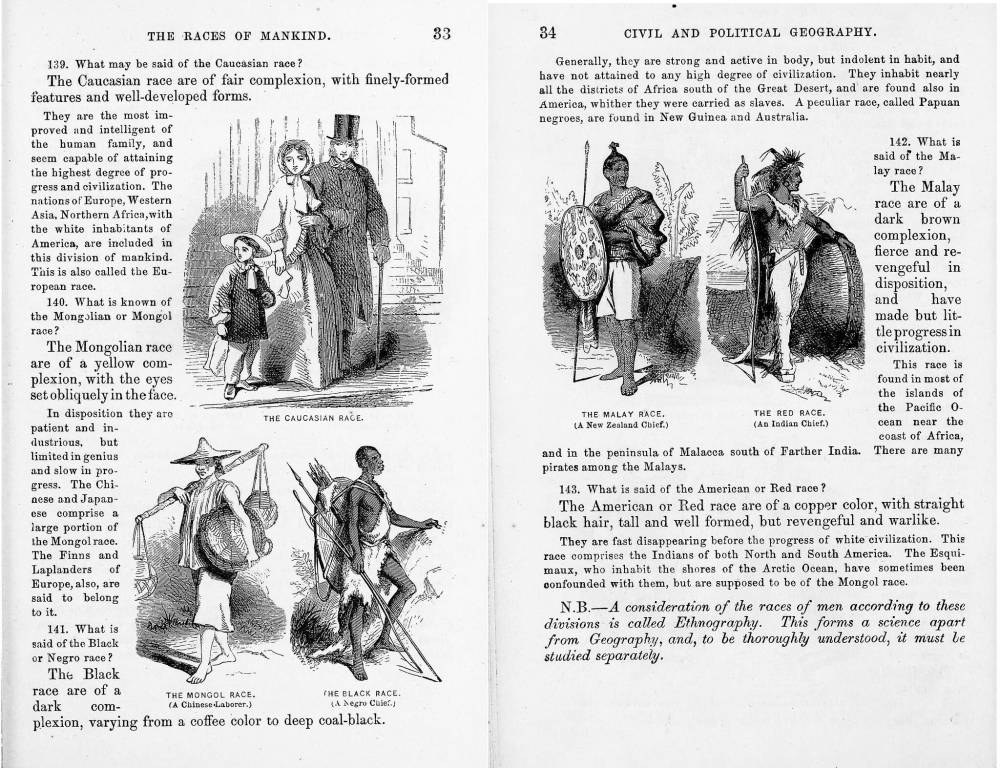

Children in public schools, divulged through heaps of fonds and archival material, were not only exposed to tropes about Indigenous peoples, racialized groups and myths about race, they were deliberately instructed to build preconceived notions of the Other. School of Racism argues that in Quebec textbooks and readers, “history was the story of the Self and geography was the science of the Others.” By this, Larochelle, in significant complexity, lays out the evolution of Canadian racism in the context of empire building, land grabbing and the perpetuation of what it meant to be civilized and Christian.

Within specific textbooks, writers and publishers began to categorize people from all over the world into specific races while dividing the world up into colonial powers. The colonial violence perpetuated globally was simplified for children: “Primary schools recycled and simplified knowledge and thus gave children a discourse that divided the world into categories that were accessible, being within everyone’s reach.” A grammar of difference was created that most certainly persists today. One only has to think of the tropes about immigrants and the conflation about housing shortages today to understand how the Other is placed into neat categories and blamed for societal woes. Never mind capitalism and poor planning — it’s the Other’s fault. Them.

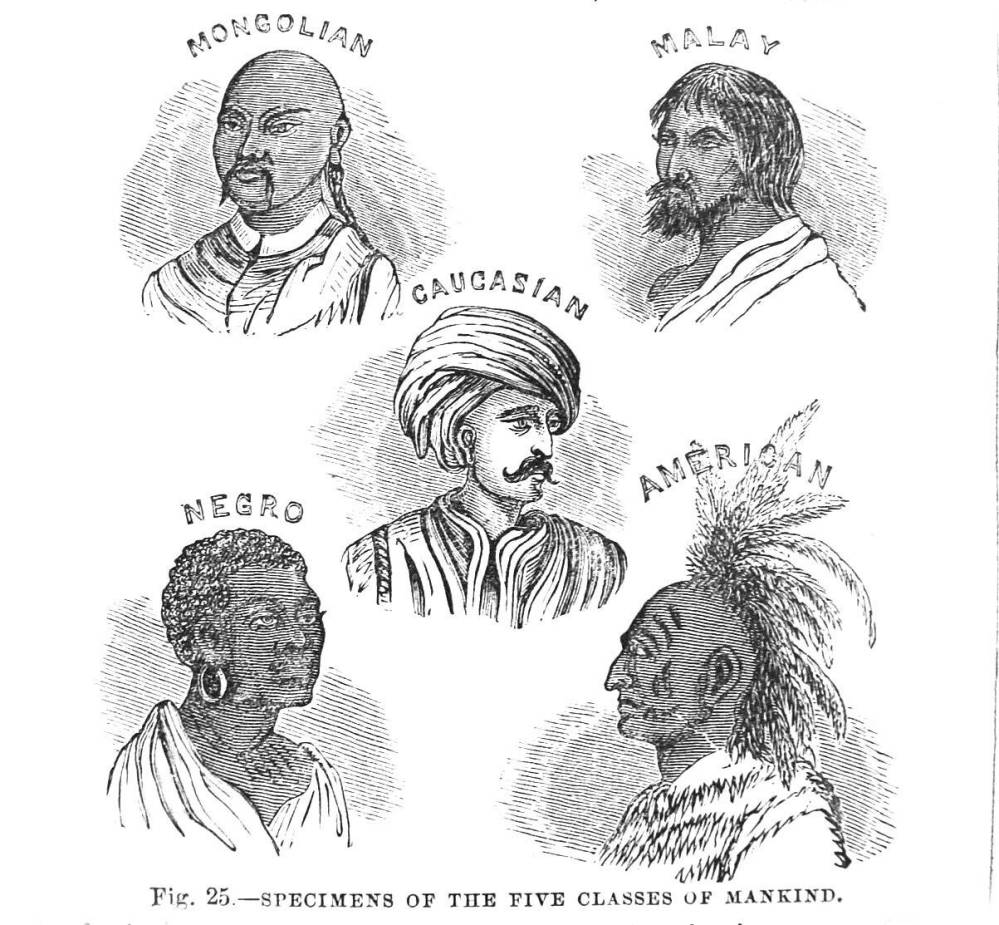

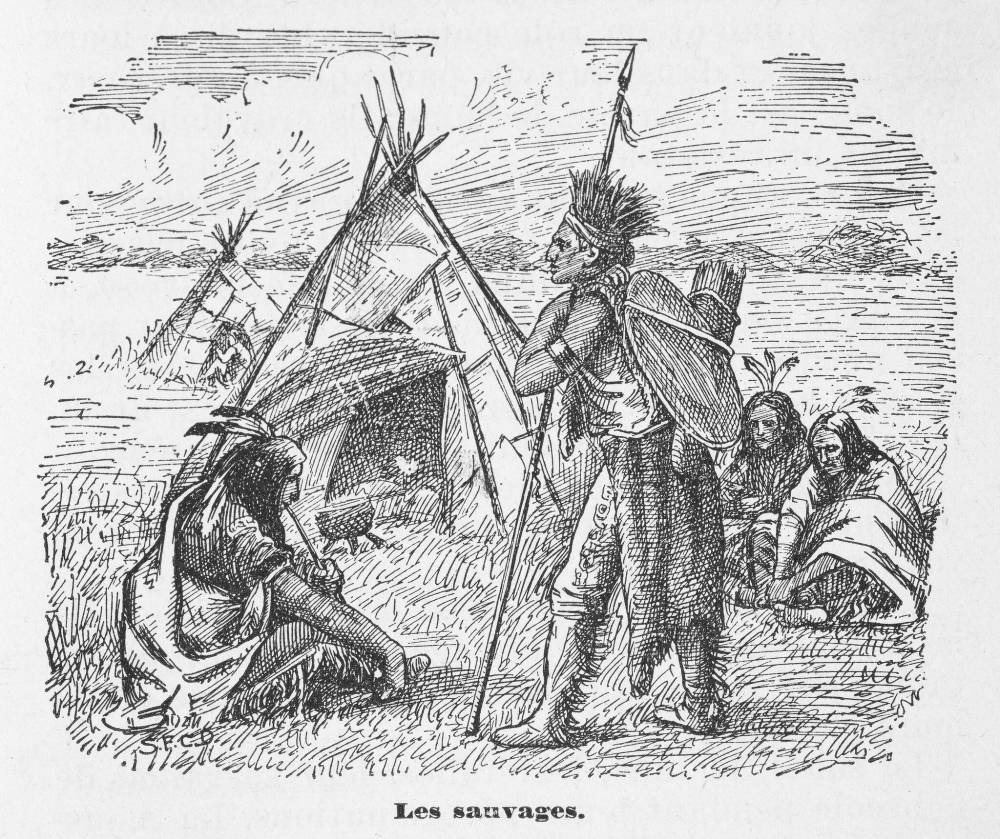

Larochelle provides haunting images from various textbooks which confirm our obsession with establishing racial hierarchies while providing laser focus on images of Black, Indigenous and Asian people. There was a relentless and unbridled desire to characterize anyone who did not fit the civilized, European and Christian mold as different, exotic and observable. For Larochelle, “These texts, and to a certain extent the schools in general, were not obliged to explain the system of racial classification; the textbooks were obliged to transmit knowledge.”

School of Racism

Part of the process of negating Indigenous peoples involved removing them from the present. Through this process, Larochelle explains that “By placing them in a different temporality, it became justifiable to appropriate Indigenous people’s [sic] in order to preserve their memory. How does such an alterity, built on the negation of its own existence, take shape?”

And it is this powerful inquiry that drives the exposing of othering and otherness. Larochelle condemns the creators of the texts and the designers of public education — not falling for presentism, but suggesting that people knew better: “In doing so, the culture transmitted in school contributed to constructing the racist field of vision of Canadian society.”

The elixir to combating racism, in a very Murray Sinclair-esque way, is through education. Larochelle sees contemporary public education as a means to bring people together, expose children to deep thinking, empathy and ethical reasoning.

Larochelle offers us hope: “It therefore comes back to the school in particular to deconstruct and unlearn the ideologies that it has taught itself for such a long time.”

A tremendous repurposing, then, of public education and a reason to support it, now more than ever — a call to action for all teachers.

Supplied photo

Lowell’s General Geography, written by John George Hodgins and published in 1867, shows ‘specimens of the five classes of mankind.’

Matt Henderson is the superintendent of Winnipeg School Division.

Supplied photo

An illustration from Father J. Roch Magnan’s Cours français de lectures gradués, published in 1902, depicts ‘les sauvages’ (the savages).

Supplied photo

A reproduction of a page from Samuel Augustus Mitchell’s A System of Modern Geography, published in 1878, illustrates the ways in which different races were often portrayed.