Baby hare’s plight sparks informative, moving manuscript

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/11/2024 (347 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

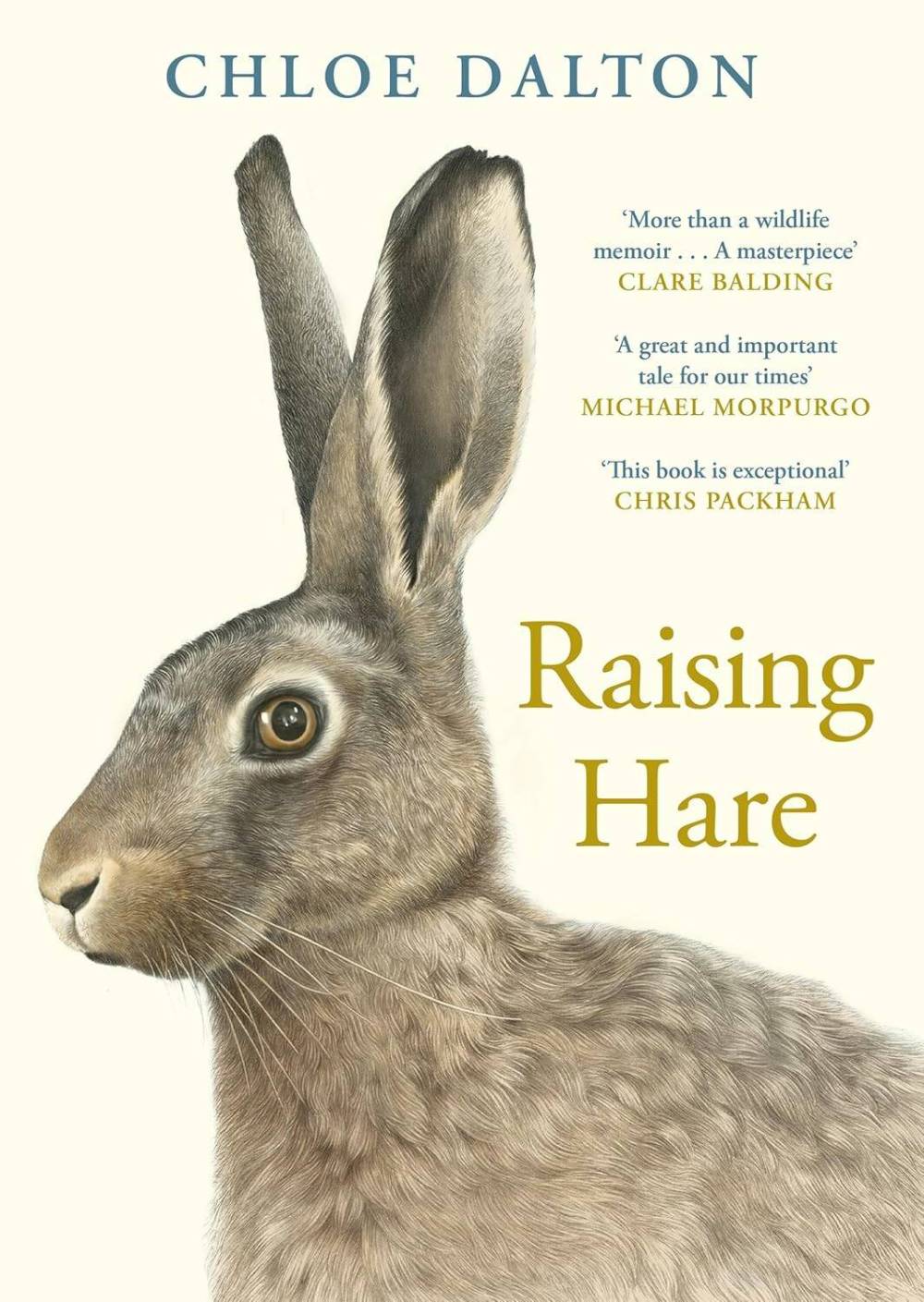

As a political adviser to the U.K. government, Chloe Dalton’s job is all-consuming, feeding her addictions to “the adrenaline rush of responding to events and crises, and to travel… at a few hours’ notice.” Unsurprisingly, when the pandemic forces her out of London to her renovated barn in the countryside, she finds herself at loose ends. And so the scene is set for Raising Hare, Dalton’s first book.

Out walking one icy day, Dalton chances upon “a tiny creature” lying stone-still on a dirt track. “I stopped abruptly,” she writes. “Leveret. The word surfaced in my mind, even though I had never seen a baby hare before.” After careful consideration she opts to leave the leveret alone “in the hope that it would hurry into the long grass as soon as I had gone, and be reunited with its mother.”

However, when Dalton returns hours later to find the baby hare “exactly as I had left it… without a scrap of cover to conceal it, with buzzards wheeling in the sky above,” she reluctantly takes the leveret home, thinking to return it to the wild come nightfall.

Raising Hare

This notion is promptly dismissed by a local conservationist/gamekeeper, who tells Dalton that “even if (the leveret) could somehow find its mother, she would reject it, since it would now smell of humans,” adding, “You have to accept that it will probably die.”

Embarrassed, worried and heartsick, Dalton tries to convince her sister, a nurse and farmer, to take on the leveret; her sister simply says “You’ll do fine,” and drops off supplement. Thus, despite self-doubt and fear, the author begins her quest to keep the leveret, who weighs “less than an apple,” alive.

Cautiously bottle-feeding it, Dalton is “captivated by the warm presence of the creature in my lap” but, determined to release the hare into the wild once it is weaned, she resists making a pet of it. After all, “if it became too habituated to humans, it would not know that out in the fields, it should fear us, with our dogs and guns.”

Fascinated by the leveret and the way its presence soothes her, Dalton arranges her life according to its “moods and movements,” noting, “I couldn’t help but compare its serenity and steadiness to the… frenetic activity that had pervaded my life for years.”

As the leveret thrives, “Each day brought new aspects of (its) behaviour at which to marvel,” and Dalton feels “drawn, against all… previous interests and inclinations… to discover everything I could about it.”

The internet provides ample information regarding rabbit care, but little regarding hares. While “(r)abbits and hares belong to the same ‘order’ of animals, Lagomorpha… (t)hey are in fact different species that never interbreed.”

Dalton turns to the London Library, ordering scientific journals and stacks of books about hares, hunting and poaching, farm machinery and folklore, among other subjects, written by an array of people across centuries. Epitaph on a Hare, a poem William Cowper wrote in 1783, proves “in many ways most useful” as a guide to feeding hares solid food.

Combining her observations of the hare with information gleaned from her extensive reading, in Raising Hare Dalton crafts a deeply felt, informative (but never didactic) and magical account of her relationship with the hare and how their chance encounter awoke within her “a new spirit of attentiveness to nature” and prompted her to rediscover “the pleasure of attachment to a place and the contentment that can be derived from exploring it fully.”

Raising Hare is, not least, a moving cri de coeur that humans revamp our industrial farming and development practices in order to restore habitat for hares and countless other creatures — and to unlearn our greed and cruelty.

Graced with Denise Nestor’s evocative illustrations, Raising Hare is an unforgettable love story and a wholehearted reminder that nature “is there for all of us, perhaps our one true heritage and source of hope for regeneration.”

Jess Woolford has been fortunate to observe hares in Albuquerque, N.M. and Winnipeg.