Loading…

The Rivers

The power and potential of Winnipeg’s waterways

Part 3 – The Final Frontier

By Randy Turner

Posted: 1:00 PM CDT Friday, Oct. 30, 2015

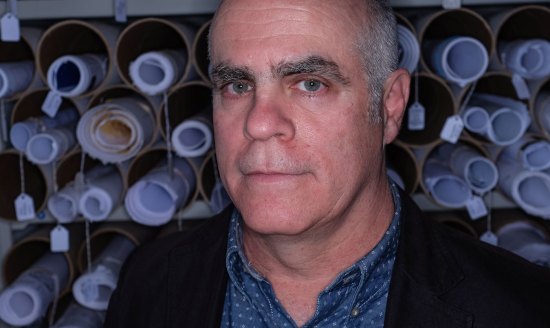

Mark Penner is standing along Waterfront Drive, in the shadow of a condo that looks like a spaceship, and talking about going where Winnipeg hasn’t gone before.

Well, for about 100 years, anyway.

Penner is the president of the Green Seed Development Corporation, which is currently erecting the $6.5-million, 40-unit structure that literally overlooks the downtown core and adjacent Red River. Designed by 5468796 Architecture, the circular condominium rises 11.5 metres off the ground.

A few years ago, the lot was vacant, but for knee-high grass. By the time it’s completed, it will mark a punctuation of sorts for development along the Red River, beginning at The Forks and stretching north to Higgins Avenue, along the waterfront.

To the south, there are now high-end $700,000 condos, restaurants, the Exchange District, Shaw Park, the Esplanade Riel pedestrian bridge, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, The Forks development — none of which existed 25 years ago. To the north and east, in south and north Point Douglas, there lies what many believe is downtown development’s unpolished gem: swaths of riverfront property that now sits filled with empty industrial buildings and vacant lots.

"That is some amazing real estate housing rusted-out machinery or empty buildings," Penner said. "If you showed me that (area) on a map I’d say, ‘That’s the most interesting place. That’s got to be THE neighborhood because it’s so close to downtown.’ But it’s not.

"I’ve been saying that for five years: right now we’re the end of the line," he added. "But someday we’ll be right in the middle. I believe that’s true."

Time will tell. In Winnipeg, after all, time is often what it takes.

Penner said he can wait. Yet he envisions a day, within a generation, when Point Douglas — once the cradle of Winnipeg society at the turn of the 20th century, home to industry and many of the city’s most prominent citizens — could become a thriving, animated neighbourhood again.

"If I were to dream about it, it would be a solid mix, where you don’t have to walk too far to have a good meal and a beer," he said. "And you’re also right down where you work and two blocks from where you live. And you’re on the river!"

A pipe dream? Perhaps, but just four years ago, the land Penner is standing on had been an abandoned lot for decades. Not so long before that, Waterfront Drive was a mud road fronting a decaying Exchange District. And 30 years ago, The Forks was a long-since-forgotten wasteland of abandoned warehouses and railway tracks.

It wasn’t too long ago that Waterfront Drive was an abandoned rail line.

So Penner is confident his "spaceship" will one day have an entirely different view.

"You have a blank slate with an opportunity to do literally whatever you want," he said. "And there are some very smart people in this city that can figure it out. You can go to other cities — Chicago, Toronto, New York City — and you can find out what works in those places. What’s proven? And we can do it.

"It will be like The Forks. It will seem crazy that it took that long and it was never there."

Point Douglas, the final frontier.

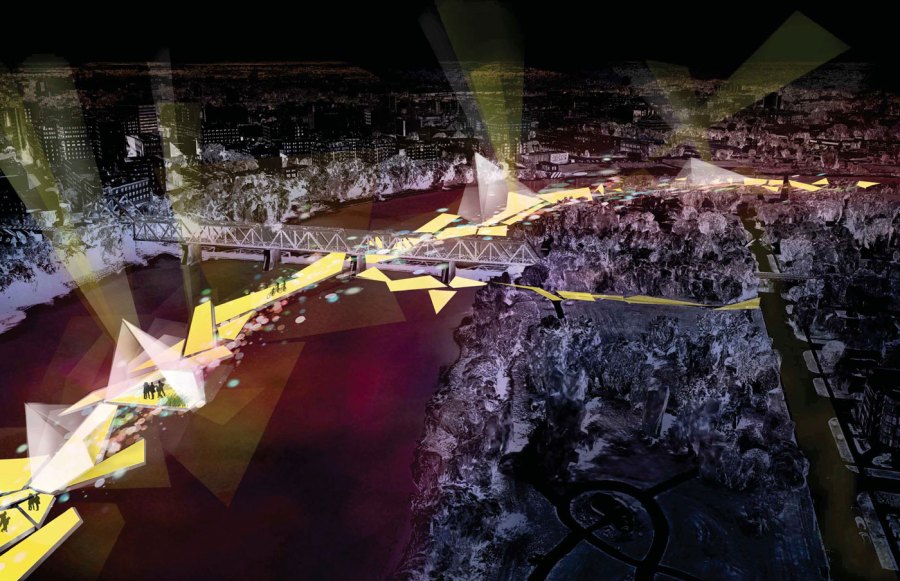

South Point Douglas has the potential to be transformed into a sustainable mixed-use community along the waterfront.

Re-imagining our rivers — 10 bold ideas.

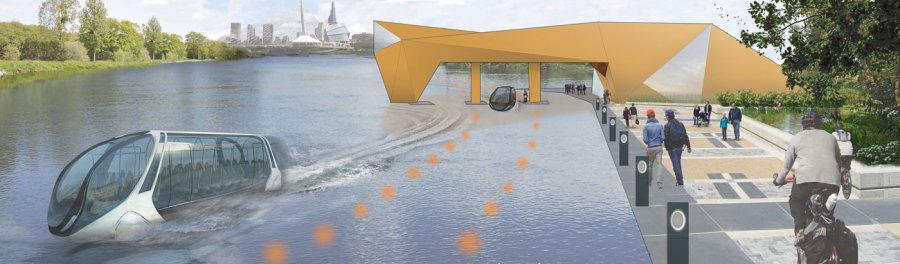

View RiverCity 2050Imagine a Winnipeg in 2050 where the Red and Assiniboine rivers are highways. They are beachfronts. They are areas of commerce, where you can buy goods from kiosks or floating barges. They are dotted with marinas and kayak and canoes launches.

In short, they are integral to day-to-day life in this city — for the first time in almost a century.

Last year, The Forks Development Corporation, following Paul Jordan’s appointment as CEO, set out to develop a long-term vision under a document entitled Go to the Waterfront — an outline of proposals — many of them modest in nature and cost — designed to eventually create a series of access points to the rivers that would eventually link neighbourhoods from Point Douglas to St. Vital to St. James.

Pedestrian bridge crossings. Bike paths. Water-bus stops. Canoe launches. Beaches and picnic areas. Skating trails. Lookouts and marinas. All in some way connected. The mission statement is to make Winnipeg the "quintessential river city", where almost every neighbourhood has a river access point that leads downtown.

There are 240 kilometres of waterfront within city limits, half of which is owned by the public, Jordan said.

"It’s all just sitting there, waiting for some energy. There’s nobody focused on it right now," he noted. "Imagine if we used that same kind of energy up and down the rivers, even just starting from The Forks moving up. Over 30 years, you could be quite transformative.

Winnipeggers don’t think of the rivers as a way to connect to neighbourhoods. Changing that mindset is key to transforming the waterfront.

"The biggest impediment is that people aren’t thinking about the waterfront as a connecting entity. They immediately go to the street — they’re thinking of the roads and the neighbourhoods. Nobody is really focused on the rivers. That’s the biggest thing, getting people to shift. Which is interesting, because that’s how we started 100 years ago. We’ve drifted away.

"I just don’t think we realize or understand how lucky we are to have this asset there. And we don’t treat it very well."

Proposals envisioned by the Go to the Waterfront concept include:

-

An all-season walkway at Armstrong Point along the south bank of the Assiniboine, with the goal of an active-transportation trail to the Assiniboine Park Zoo, the Corydon Avenue district, the legislative buildings and Osborne.

-

A restaurant overlooking the legislative grounds on the Assiniboine, a waterfront plaza at the Governor’s Landing, a permanent dock at the Osborne Village Landing for summer and winter access. A bridge crossing from north of the Assiniboine to Fort Rouge Park.

-

A marina north of Provencher Boulevard on the Red. A plaza on the east side of Esplanade Riel and the development of restaurants/businesses facing the river on the south end of the St. Mary Road bridge, facing the river.

-

A pedestrian/bike bridge across the Red in Norwood at Lyndale Drive Park, scenic lookouts at Churchill Drive, Lyndale Drive and a community paddling/kayak launch along Churchill Drive.

-

A year-round voyageur-themed riverfront trail linking Fort Gibraltar to The Forks, a pedestrian/bike bridge over the existing rail line linking Waterfront Drive to North Tache/Whittier Park, waterfront plaza at the Alexander Docks, a voyageur-themed park facing the river off South Tache.

Included in the waterfront proposals is a $4-million project, being pushed by Coun. Matt Allard, to build a promenade along the Red along Tache Boulevard, south of Provencher — highlighted by a "Tree Top Lookout" across the Red to The Forks.

Allard wants to brand Winnipeg as River City and says the Tache lookout, if constructed, would be the "Selfie Capital" of Winnipeg, with the Canadian Museum for Human Rights and Esplanade Riel providing the background.

The project has secured a $1-million pledge from the Winnipeg Foundation and Allard has identified another $1 million in possible municipal funding avenues. The $2-million shortfall, he said, will be submitted to the city’s capital budget for consideration.

"This is a key project to get off the ground and dress up our image," Allard said. "It should be a high priority for the city, with the value and potential there."

If it ever happens, a promenade down Tache would be another piece in the waterfront puzzle.

Michael Scatliff, president of the environmental design firm Scatliff + Murray + Miller, which participated in the Go to the Waterfront project, said the concept of developing access points, then linking them, is as old as the city itself.

"Commercial activity and residential neighbourhoods, it’s common to all of them," Scatliff said. "Look at each opportunity to integrate water and waterfronts and you increase property values and you increase visitorship. Satisfaction. All those things go up.

"Every neighbourhood should be awakened with its own waterfront. I don’t care where you live. It doesn’t have to be The Forks."

But Scatliff cautions parks or beaches are virtually useless without supporting programs to draw a crowd. It’s equally important, he said, to ensure a quality of water that at least doesn’t repulse visitors — an undisputed factor in the last half-century.

"It wasn’t until we built the river walk that people went down and saw condoms and toilet paper floating by in the water… it seemed to change the way people expected accountability from our governments," Scatliff said. "That was a big step in people seeing and smelling the water up close, and they started really getting interested in the quality of the water."

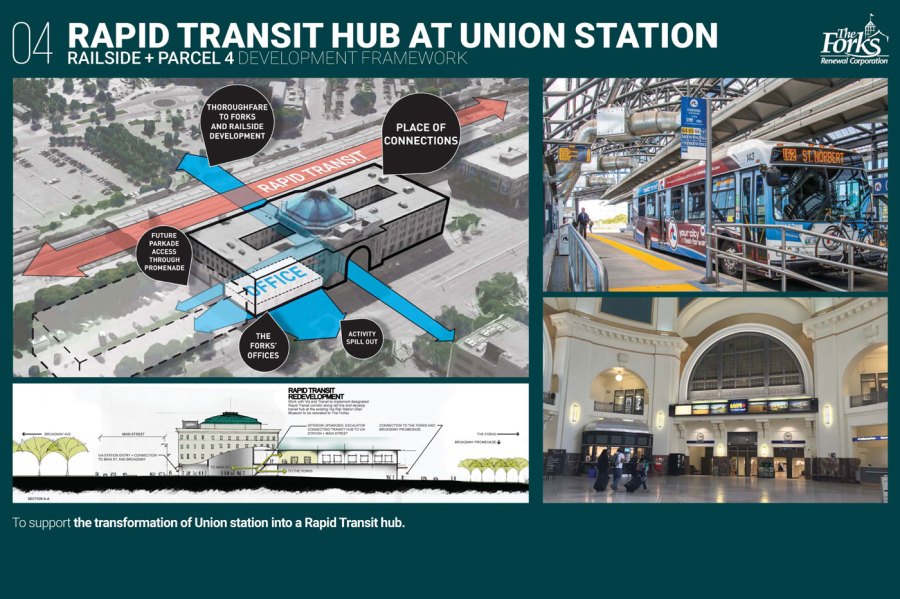

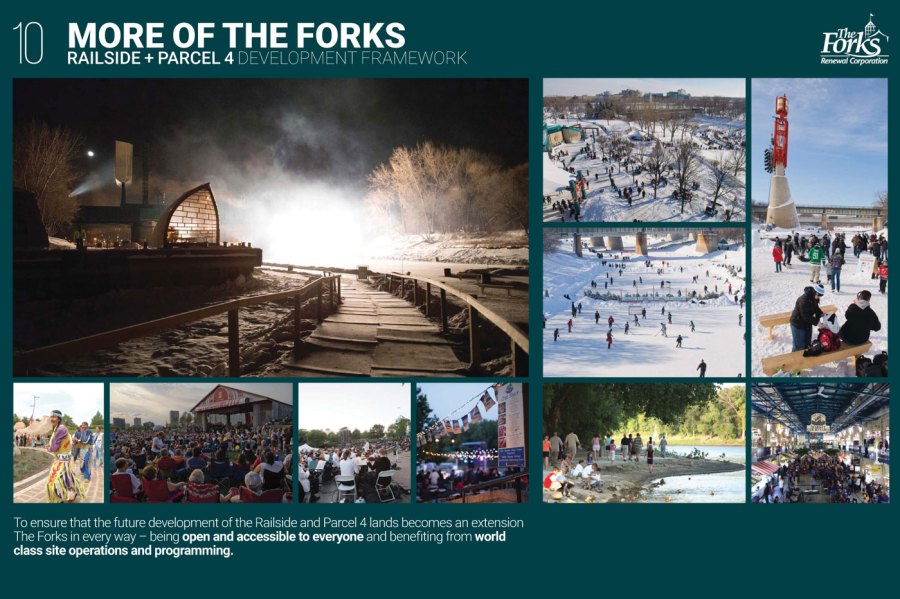

The Forks’ vision for railside and Parcel 4 land.

What transpires at The Forks over the next few decades will hinge largely on a 12-acre parcel of land, now a parking lot, that abuts behind Union Station and north towards Shaw Park on Pioneer Avenue. The development of that parcel of real estate — where city council once infamously deliberated constructing a water park — could be the lynchpin for the entire downtown district, Jordan said.

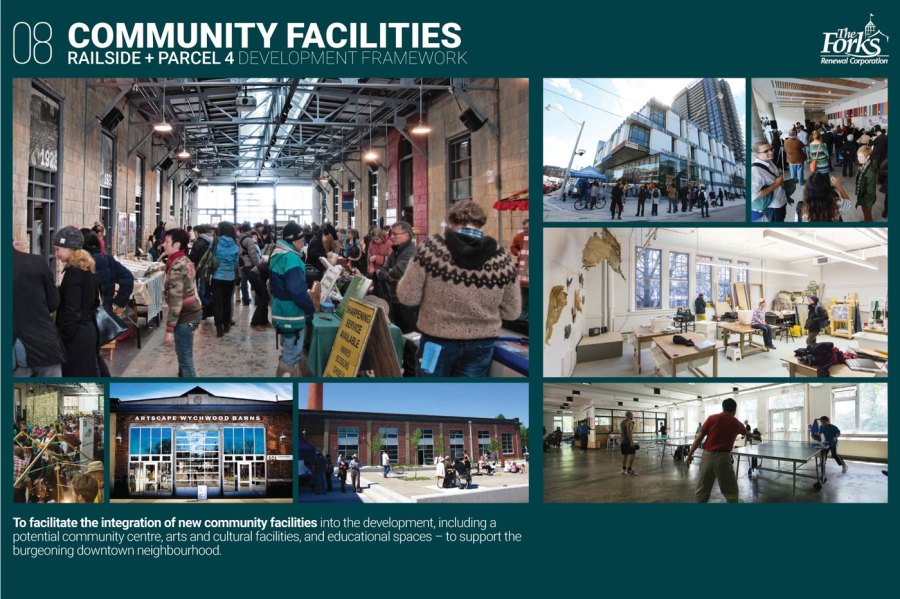

Essentially, it will be like dropping condominiums, green space and commercial development smack dab into the heart of The Forks, providing a dynamic that has not existed since, well, forever: permanent residents.

At the same time, the property will be the guts inside the present tourist attractions, linking The Forks — if done properly — to Portage and Main.

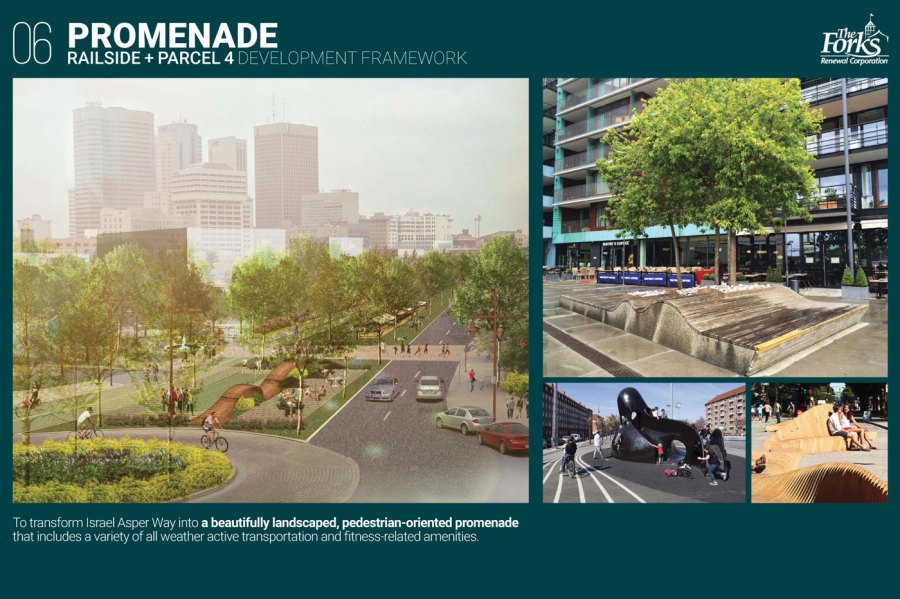

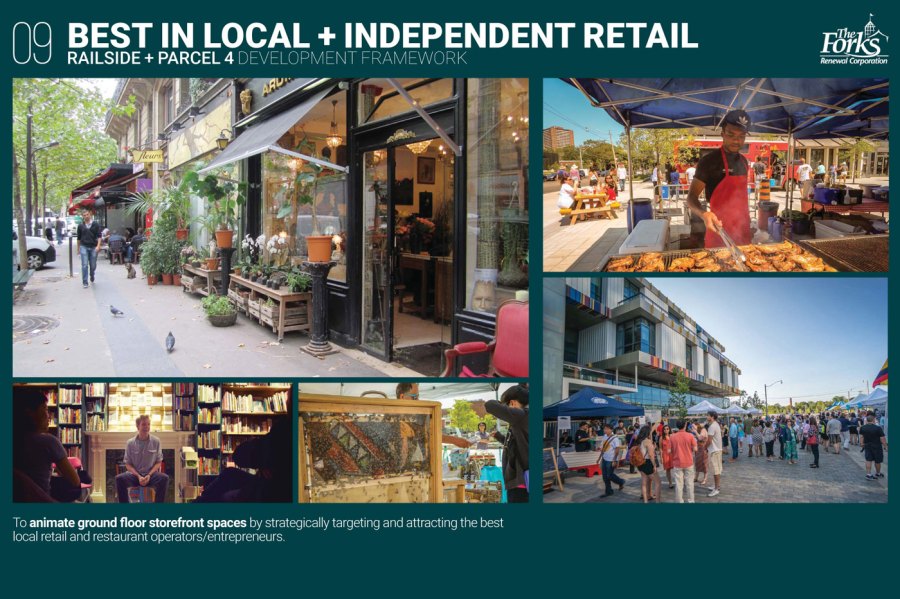

The Forks Renewal Corporation released several glossy proposals for the site in September, titled 10 Big Ideas that floated artist’s renderings of happy, young people strolling/biking/walking dogs down brightly lit promenades between glassy condos: an urban village of retail shops, perhaps a grocery store, with links to St. Boniface, the Exchange and Waterfront Drive and west of Main Street into the downtown entertainment district.

"The potential is huge," said Johanna Hurme, a founding partner of 5468796 Architecture, which was a consultant on the proposed Forks development. "It could be all the ingredients that are missing from downtown. It could be a catalyst for downtown to take off in a major way."

"You can’t just build a big museum and hope that it will happen, especially in Winnipeg," added Brent Bellamy, a senior design architect for Number TEN Architectural Group. "You have to be careful with what you do, and these parking lots are ground zero for it. If you do this right, then it spills off into Main Street, then spills into the Exchange District, it spills into St. Boniface.

"It really becomes the centre of it all. I have my fingers crossed."

Jordan is convinced selling condos in The Forks would be the least of his worries. "I could sell them all tomorrow," he said. "I’m just worried about getting it right. Because you can kill a street. And the scale has to be right."

After all, for proponents of waterfront development, the components are open to debate. You don’t want crass development? Fine. Want enough manicured green space to, say, line a promenade from Union Station directly to the Canadian Museum for Human Rights? Go for it.

Jordan is also reluctant to crystal-ball too far ahead in a city that historically develops at a glacial pace.

"I’m not a big believer that you have the plan set out for 30 years," he said. "Who knows what it’s going to be in 30 years? I mean, nobody had this in mind, but they allowed it to happen. Smart people have been working on it for 30 years, and this is the result. That’s the same methodology that we use along the waterfront. As projects come up and opportunities present themselves, it’s doing something in a co-ordinated-linked-visionary type of fashion."

"We know we can do it. The thing with the waterfront is about waking people up," Jordan added. "Saying, ‘Hey, it’s there. Look at it differently.’ Get out of your car. Go on the river for a skate. Use the rivers as opposed to turn your back on them."

Jordan is not alone in his ambitions. Turns out, the desire to reconnect with waterfronts is a global urban phenomenon that transcends cultural and geographic boundaries. In North America, major cities such as Pittsburgh (the Riverside Task Force), San Antonio (the River Walk) and Oklahoma City (the Bricktown Canals) — just to name a few — have redefined their cores with major, inventive waterfront projects.

This summer, the Landscape Architects Network website noted: "We are living in an era in which for the first time since the Industrial Revolution we are witnessing a complete shift in the way the relationship between the city and nature is represented in our cities. Architects, planners, landscape designers, artists, politicians and society are getting together to find ways to reintegrate nature into the cities through their often-forgotten rivers."

The site listed 10 cities around the world that have embarked on major riverfront projects, from Paris to Seoul to Singapore.

"As we’re getting more populace, as the density of our cities increases, there is this clear idea that connecting you back to quote-unquote nature," said George Kapelos, assistant professor at the department of architectural science at Ryerson University. "If you live near a river area, you don’t have to pack your car and drive two hours out of town to sit by a lake. You can find that in your own community. So rivers become important opportunities to re-establish that relationship to the natural world.

"There’s an innate tendency for humans to find a way to restore themselves or find an opposite condition than the urban condition they seem to be confronted with on their Monday-to-Friday, 9-to-5 schedules."

Consider: Kapelos is currently judging a competition to improve the waterfront on the Thames River in nearby London, Ont. He notes, without irony, a similar campaign to improve the Thames in London, England.

Kapelos noted Winnipeg shares the same challenge, in the same psychological climate, as countless urban centres: to redefine the forgotten waterways that fell out of favour and thought when city planning and transportation routes shifted away from rivers in the early 20th century.

And he expects the trend to continue.

After years of neglect, Bricktown in Oklahoma City has been transformed into a thriving entertainment district.

"It’s no longer something we want to take charge of, we want it to help restore us, both emotionally (and) in terms of our communities," Kapelos said.

"I think there is a hunger among urban populations for some kind of connection to place, to landscape, to the cycle of nature. Places that are a little less predictable than going down a city street."

In Chicago, they actually reversed the flow of the Chicago River. In San Antonio, they essentially built a tunnel under the city to channel overflow of the San Antonio River. In Oklahoma City, they built 1.6-kilometre canal into a district of derelict brick railway warehouses (from the North Canadian River) turning the strip into an entertainment attraction that now draws more than seven million visitors a year.

Of course, Winnipeg is already protected by the Red River Floodway. However, there are parties, such as The Forks Development Corporation, that have long lobbied for the existing floodway to be used to a greater extent, which would require federal and provincial approval, to further reduce levels during summer months inside city limits.

Jordan argues controlling these levels would: a) reduce riverbank erosion, b) encourage private development on the waterfront and c) increase recreational use (boats, marinas).

Fluctuating river levels are eroding riverbanks, destroying trees and hurting water-based businesses.

"The economic benefits of doing it outweigh the not doing it," he said. "All the physical structures (the floodway) are in place. It’s just a matter of how you use it.

"It’s the… out-of-control floods that are killing us. They’re killing the riverbank, they’re destroying trees. They’re killing our business."

The Forks’ river walk, which can draw 10,000 visitors in a weekend, is under water more than above. The 800 boats that were once moored near The Forks are now docked in Gimli or Kenora, but for less than 100, Jordan added.

"All that money is gone," he said.

Any solution, Jordan said, would involve compensating landowners affected by flooding, which he maintains would be a fraction of the cost relative to the economic benefits derived from more predictable and controlled water levels within the city.

"Somebody has to start wrestling with that," he said. "There has to be something that works for both people (inside and outside Winnipeg). Someone needs to start investigating and helping them (politicians) with a bigger window. Sure, a politician has a five- to 10-year window. This may be longer than that."

Two problems: the myriad of government departments that control various aspects of rivers — from property to navigation to fisheries — make any diversion changes almost paralyzingly difficult. Secondly, such a discussion surrounding the floodway invariably is condensed into the following: why should landowners downstream have their land flooded so Winnipeggers can take Fido to stretch his legs on The Forks’s river walk?

Which is why any talk of further controlling the Red or Assiniboine is a political no-fly zone.

The provincial minister for municipal government, Drew Caldwell, has seen Jordan’s long-term plan, calling it "an ideal, good road map for development along the river corridors." He’s heard the arguments for river control within city limits. But bottom line: a provincial government already under heavy fire for flooding damage resulting from use of the Portage Diversion isn’t open to further increasing the risk.

"There’s been dramatic negative impacts to producers all up and down west of Winnipeg on the Assiniboine," Caldwell said. "Having any sort of plan that would negatively impact those producers by design is a non-starter."

In fact, Manitoba Infrastructure and Transportation is currently undertaking a study on using floodway controls for the Red and Assiniboine, which is expected to be released in the near future. "I’m not going to prejudge the report," Caldwell said, "but I suspect that won’t be a viable option."

You can’t deal with any one of (the rivers) in isolationDrew Caldwell, provincial minister for municipal government

In essence, there are those (in Winnipeg) who believe there could be hundreds of millions in tax revenue and development if steps were taken to control the rivers inside city limits. And there are those who say it will cost hundreds of millions in tax dollars to compensate for flood damage if the former ever happens.

Caldwell, for example, notes it was only four years ago there were 5,000 residents evacuated from his hometown of Brandon due to spring flooding on the Assiniboine.

"It’s complicated," Caldwell said. "You can’t deal with any one of them (the rivers) in isolation. There’s not a simple fix to it. But we are willing to do the best we can to maximize that asset.

"How to resolve the tension between these two parties is going to be critical to this."

Ultimately, Caldwell said any solutions must account for the "very real and dramatic fluctuations" in river levels "particularly when the climate is changing as much as our climate is changing now."

In other words, the minister concluded: "The rivers are reminding us who’s boss."

A vision for Winnipeg’s river development

Glen Manning, a principal with HTFC Planning and Design, echoed concerns about engineering solutions. Winnipeg, after all, is but a dot in a much larger Red River drainage system.

"The simple thing is to say, ‘We’re just going to control it’," Manning said. "We’re going to keep it at a low level so we can have access to the river walks and we can develop (commercially) as close as we can (to the river). That would be great on a bunch of fronts. But that has a lot of implications that are quite profound. It’s not about flooding a few properties elsewhere. It has to do with the whole way the river actually works, and the river and the banks are part of a complex system that’s several million years old. We have to be careful that we’re not messing with something beyond that."

Hurme leans toward developing the riverbanks as accessible green space.

"We can’t control the nature," she said. "We shouldn’t even try, but try to build so that both can coexist so the river can fluctuate. How you tie the city to the river is key.

"You have to let the river breathe. But I also think there’s room for big ideas," Hurme added. "It shouldn’t just all be butterflies and prairie grass blowing in the wind. That’s not the only way."

Still, while the potential for future development influenced by the rivers could be transformative for Winnipeg, obstacles exist at most every turn.

Want to attract residents to the core area? Well, don’t forget about an antiquated sewage system that, unlike most of the city, has sewer and water in the same pipes. "So if you want to create a more dense downtown you have to actually, in time, replace the sewer and water infrastructure. That’s an enormous expense," said Scatliff.

Want to raise a new urban community on south Point Douglas? Not before dealing with acres of heavily contaminated land that was for decades home to pulp mills and soap factories. "It would make it more challenging, for sure," conceded CentreVenture CEO Angela Mathieson.

Then there’s the matter of money, as always. The amount of privately owned properties in Point Douglas won’t come cheap — especially if the landowners smell major urban renewal and government dollars.

Still, roadblocks aside, urban planners agree the inertia created when shovels went into the ground at The Forks three decades ago — then spread north to the intersection of Higgins Avenue and Waterfront — won’t simply vanish now.

"That’s going to take a lot of planning and organization and a lot of money," said Robert Galston, a master’s student in city planning at the University of Manitoba. "But development pressure will move up there over time. It’s moving up there already."

Sometime, some way, Point Douglas will be next.

Contaminated land and antiquated infrastructure are some of the stumbling blocks to overcome in redeveloping Point Douglas.

"South Point Douglas is an emerging conversation," Mathieson said. "People are logically saying, ‘What should we be doing here?’ I totally see that happening in the next 30 years. But it takes some vision on the part of governments."

Point Douglas Coun. Mike Pagtakhan believes in the "when" not "if" future for his ward.

"Basically, about 15 years ago I was wondering, ‘What’s taking so long?’ " Pagtakhan said. "But I think what’s happening is Winnipeg is developing at its own pace, and that rate is healthy. When you rush something it never turns out right. Good things take time.

"People are catching on. Eventually, it’s going to fall into the hands of a developer. The stars are lining up. It’s going to happen."

Mathieson would favour a "good neighbourhood that makes sense" for Point Douglas. Something affordable.

"We need a plan that’s mountable," she said, "that supports the infrastructure."

Or you could pretty much bulldoze the entire area, build a $250-million world-class waterslide park next to a rapid-transit depot and build a beach on the waterfront. Or a massive hospital complex. Or a major aboriginal development centre.

Why? Because, as Scatliff contends, Point Douglas is the last remaining untapped and most potentially valuable real estate in the city core. So why not think big, with a clean slate?

"There’s usually a bigger vision that’s something you assemble from Year 1 to Year 20," he said. "This could evolve, but let’s start by being provocative first."

In the end, it appears the smart money on Point Douglas — if not the most money — would see Point Douglas slowly evolve into a more upscale, artistic neighbourhood with, ideally, several businesses and retail shops constructed towards the actual point.

Ceramic artist Jordan van Sewell, who has lived in his three-plot home along the Red for almost three decades, said the change, while subtle, is already beginning to occur. Point Douglas is quietly becoming home to a growing number of the city’s artistic community (cheaper than Osborne, some say) and well as young immigrant families.

"It’s almost as if artists can predetermine where the shifts and trends are going to go because they seek out beauty and simplicity, then live in it because it’s affordable and accessible and all those things artists require," Van Sewell said. "Why do we have to say, ‘OK, let’s roll up our sleeves and tear this (stuff) down. Now we’re going to build something.’ No, no. It’s already here. We’ve already set the tone and the pace. Let’s develop off of that strength."

Penner, the developer, has a similar vision to Van Sewell, the artist. Not just to develop Point Douglas, but to reconnect it with the city. Make it a focal point instead of a long-forgotten tract of land that was once a vital Winnipeg hub.

You know, like The Forks.

"I actually think Winnipeg is up for the challenge," Penner said. "When you look at the last 10 years or even the last five years, how Winnipeggers have embraced the winter. Now my favourite part of winter is going to eat dinner on the river (at the pop-up restaurant).

"Now that seems just like what we do in the winter. Ten years ago, you might be asking, ‘Why would you put a huge tent up, internationally designed, that doesn’t seem like it’s going to happen?’ Hopefully, in 10 years water taxis will be how my wife and I go from Osborne to go downtown instead of driving all the way and fighting for parking."

Maybe in 20 years, you could leave The Forks and literally walk tens of kilometres along the Red or Assiniboine, and return by water taxi if it’s getting too dark. In 30 years, who knows what advances in technology will allow.

But for now, Pagtakhan will settle for a parkette along the Red, just east of Waterfront Drive — a spot where Van Sewell has been coming for inspiration for almost 30 years. The artist calls it his "million-dollar view." The parkette will include a small landing on the Red complete with a dock launch, a path, sitting area and some lighting. Pagtakhan hopes the modest $40,000-to-$60,000 project will be completed by next summer.

It’s not momentous, nor transformative. At least not in the big picture. But on a philosophical level, it’s exactly what the city should strive for, Pagtakhan reasoned.

"There’s so much history within our city with our river system," he said. "There’s an ancient history, the aboriginal culture, the trading history. Water, it does something to your psyche. It’s symbolic of life. We’re born from water. The more we can honour our connection with rivers the better.

"Our city grew up around the rivers. It’s part of our emotional health. The more we can draw Winnipeggers to the rivers, the better our city will become."

So what has Winnipeg lost in becoming estranged from its rivers? What has the city been missing?

"We’re missing The Forks on a good day," Van Sewell replied. "On a good day at The Forks you’re thinking, ‘Where the hell am I?’ You’re in Winnipeg. And it’s as distinctive as City rye bread and Jeanne’s cakes. You’re at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine, with all the historic wonderment (of the past).

"We could have all that all along the river. There’s no reason we couldn’t be doing that all the time… a palpable vibe that shows that civic leaders have considered and carefully thought this out, but executed it well. So that the people of Winnipeg are not only enjoying it, but they’re thriving.

"It would put a mindset in that we’re Winnipeg, and we’re not trying to be anybody else. This is what we need to do to continue to be Winnipeg."

Finally, it should be noted Van Sewell isn’t just an acclaimed artist, but president of Heritage Winnipeg. So maybe it’s his spiritual connection with the Red. Or maybe Van Sewell just understands he won’t be the first, or the last, to just stand on that riverbank and enjoy the view.

After all, 6,000 years is a long time. Long enough, perhaps, to make amends.

"It’s the river, it should be a priority," he said. "It’s a living organism that we’re just here for a few years to enjoy. Why don’t we make it a better place when we leave it? We’re here as stewards.

"We have to look after it until the next people come along."

Writer: Randy Turner

Multimedia and visuals: Tyler Walsh, Mikaela MacKenzie, Mike Deal

Digital design: Rob Rodgers

Production co-ordinator: Mike Deal

Art director: Leesa Dahl

Project editor: Scott Gibbons

Special thanks to Appachu Biddanda at Harv’s Air, Tom Monteyne at Syverson Monteyne Architecture Inc., David Penner and StorefrontMB, and Nicolas Schraml.

![Under[used]](https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/03/Rivers3-render-UnderUsed.jpg?w=900)