Armstrong’s Point residents hold on to history

Neighbourhood will be Winnipeg’s first ever heritage district

Advertisement

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/12/2016 (3211 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

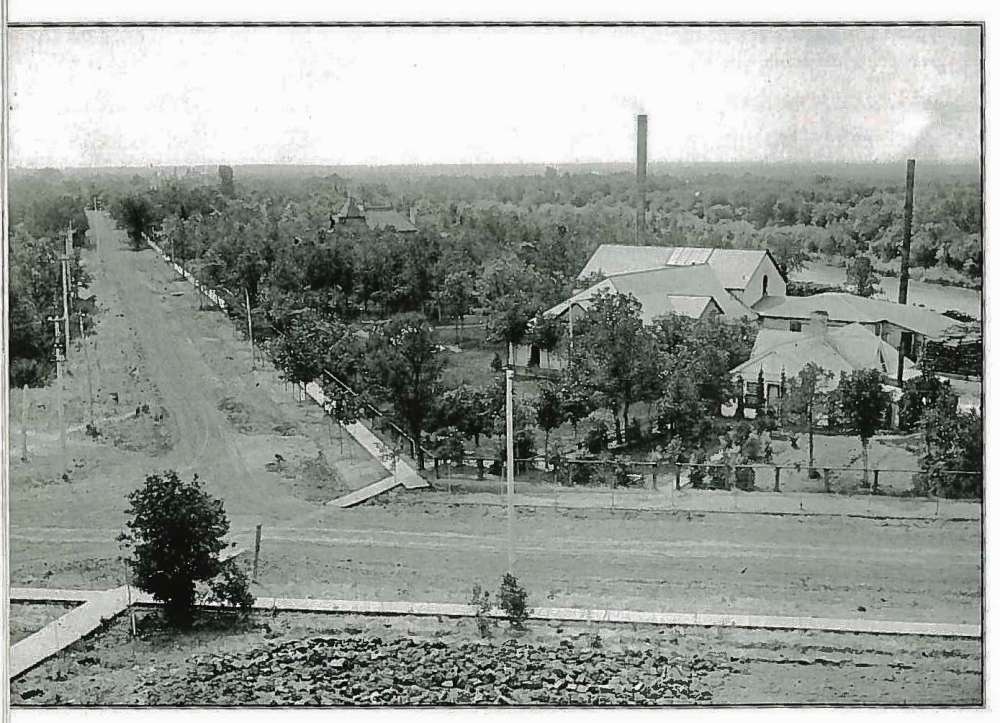

In 1881, John McDonald and a man known as E. Rothwell purchased 54 acres of land on the Assiniboine River for $28,000 with the intention of subdividing the property into lots for houses.

If McDonald and Rothwell were able to walk the streets of Armstrong’s Point today, they might be pleasantly surprised to see that, although the skyline has filled up with apartment towers, and some mansions have given way to bungalows,, much of the neighbourhood has stayed the same.

According to neighbourhood residents, that’s no accident. The Armstrong’s Point Association has been fighting to maintain the look of the historical neighbourhood, and it now has the City of Winnipeg’s support. Armstrong’s Point will become the City’s first heritage district, a designation made possible by recent bylaw changes.

“The city had some charter changes back in 2011… before that time, we couldn’t designate parcels of land so we could only designate footprints of buildings,” Jennifer Hansell, senior urban designer in the planning, property and development department for the City of Winnipeg, said.

“We started looking at doing districts at that time because we had never really done them and they’re very common elsewhere, so it was sort of another tool in our toolbox that we were looking to use.

“Armstrong’s Point came to light as a perfect case study for us to work on.”

In collaboration with the area’s residents, the City is now well into the planning stages of naming the neighbourhood Winnipeg’s first heritage district. The designation will protect the neighbourhood — currently R1 — from any proposed zone changes, large multifamily and commercial developments.

While many Winnipeggers fight against similar changes in their own communities, Armstrong’s Point residents will rest assured that the “look and feel” of their area will remain the same.

Thomas McLeod and Jim Fielder’s home was built in 1911, and the couple has invested time and money into maintaining the historical character of the property.

“You don’t buy an old house without recognizing that you’re investing in something that’s likely to be a money pit,” McLeod said.

“You have to be willing to say, ‘I’m investing in a home that I realize I’m caretaking.’ And a lot of people take that kind of pride, so a designation means quite a bit, because why would people invest to care for their home and the presence of their home if the City is not equally going to value it?”

The pair have the original blueprints to their house — a big selling point when they purchased it 10 years ago — and are planning to rebuild the original veranda that adorned the home in the early 1900s. When a window needs replacing, they spend the extra money on special leaded glass.

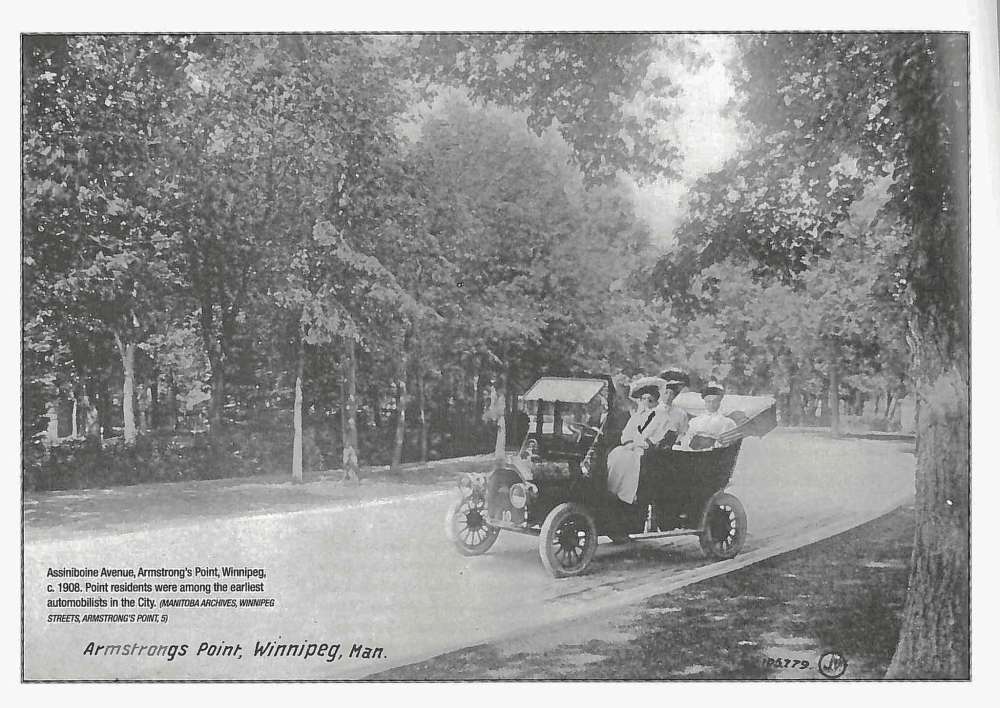

“There’s a certain feel and beauty to this neighbourhood that comes from the planning, that it goes around the crescent, and it’s three streets and it’s not that it’s uniform, there’s a lot of variety, but it’s walkable, broad avenues, wide views, and we’re trying to keep that general public space accessible and thriving,” McLeod said.

Past meets present in the west

A heritage district designation is not meant to be exclusive, Fielder says.

“Even though it’s called ‘the gates’ and we do have big gates… we want people in the area,” he said. “A lot of the residents are really proud that it’s open. It’s not that we want to become an enclave… we encourage things like the Manitoba Marathon, we have our home tours.

“The idea is not to make us exclusive but to save something for the citizens of Winnipeg.”

The designation will not ask residents to adhere to minute requirements — things such as house size and distance from the street will be important when building but the guidelines will not be strict or overbearing.

“It’s not going to be something that says you can’t paint your door red,” Fielder said. “It’s not drilled down to the absolute. It’s moreso that when you come to this area, it will be an understanding that it’s a heritage area.”

He and his husband McLeod have both been presidents of the Armstrong’s Point Association and say the residents have been active in looking after the neighbourhood in a number of ways. Considerations for a heritage district have been in the works for two years but before that residents regularly attended city council meetings to push back against large developments in the area.

“You don’t win (every council decision) but it’s developed a framework,” McLeod said. “They have a track record of decisions that support R1 so they’re saying, if this is clearly what the neighbourhood wants then perhaps we need to designate it so there’s a clear understanding for development, so there’s less confusion and people aren’t going down blind alleys thinking there’s an opportunity to develop here when there isn’t.”

He says many other neighbourhoods in the city have faced similar tensions between wanting to hold onto a historical feel with large homes and developing large, profitable condos or rentals in the city’s increasingly desirable core. McLeod uses Osborne as an example where multi-family housing has changed the neighbourhood.

“When you start knocking together three or four lots to build a condo development, you change the urban fabric in a neighbourhood, and so it’s a big radical change,” he said.