Winnipeg’s short-lived numbered street system

Advertisement

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/10/2022 (1161 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Winnipeg’s street system was well established by the time the railway came to town. As a result, it didn’t benefit from the cookie-cutter style of town planning used by railway surveyors that featured perfect grids and numbered streets.

Author and historian James Gray wrote in one of his Winnipeg Free Press columns: “If Winnipeg originally had been laid out by surveyors instead of meandering cows, and if the pioneer urge to erect buildings in the most outlandish places had been squelched, Winnipeg would have little cause to worry about town planning today”.

As civic officials spent time in the West and saw its towns grow in an orderly fashion and the ease with which they could navigate using street numbers, some yearned to bring the system here.

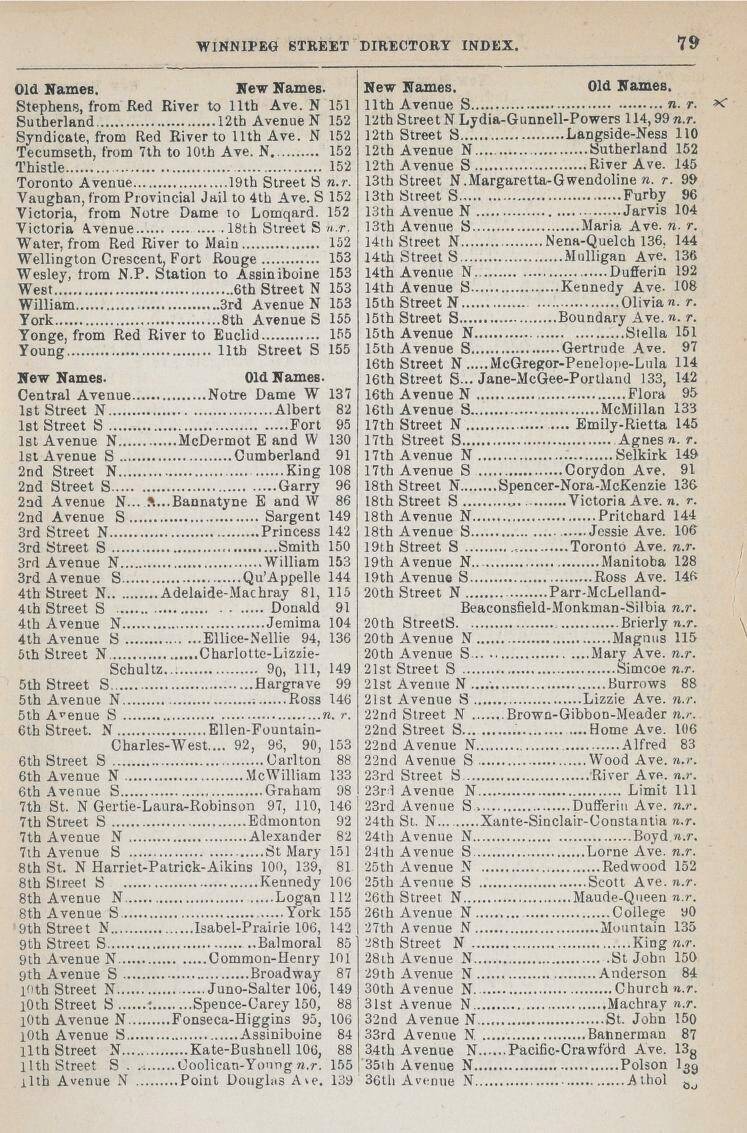

The 1891 Henderson’s Street Directory carried a multi-page index showing Winnipeg’s new and old street names.

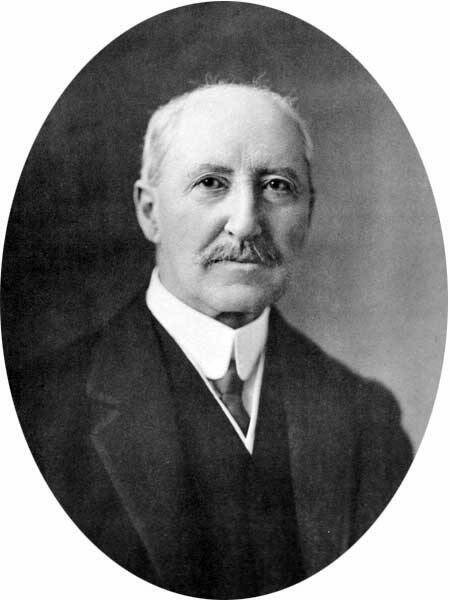

Winnipeg hired its first city engineer in 1885. Henry N. Ruttan, a former railway engineer, soon turned his attention to bringing order to the city’s street system, including numbered streets.

Ruttan found a political ally in Alderman John B. Mather, a McDermot Avenue merchant who, at a February 1891 board of works meeting, spoke in favour of a proposed bylaw to convert to a numbered street system. Mather got his colleagues’ support and Ruttan was asked to put the plan to paper.

The following month, Ruttan was back before the board with map in hand. It called for streets north of the Red River and east of the Assiniboine River to be numbered to the city limits. Portage Avenue and Main Street would keep their names and Notre Dame Avenue would become Central Avenue.

Central Avenue was “ground zero” as the numbering of avenues began on each side of it and they would be called ‘north’ or ‘south’ in relation to it. For instance, Cumberland became 1st Ave. S. and numbers increased until reaching Assiniboine Avenue, which became 10th Avenue South. On the other side of Central Avenue, McDermot became 1st Avenue North and numbers increased until reaching Luxton which became 36th Avenue North.

The numbers for streets began at the Red River and ran west to around Home Street. They were designated ‘north’ or ‘south’ depending on which side of Central Avenue they fell.

The plan was approved and sent on to city council which unanimously supported it. Numbered streets went into effect on March 31, 1891.

City engineer Henry N. Ruttan brought order to the city’s street system, including a numbered street system, which he had to dismantle in 1893.

The public didn’t take to the new system. In letters to the editor, some called it confusing, others lamented losing the names and the meanings behind them. For most, though, it was likely the basic human resistance to a quick and drastic change to a system they had always known.

A scan of the daily papers a year later shows that business and classified ads almost exclusively used street names. Only city notices used street numbers. By this point, some alderman realized their error and began calling for the system to be changed back.

Two years in, there was still no sign of the public getting on board, so city council voted to repeal the numbered street system and revert to the old street names effective Oct.31, 1893.

Christian Cassidy

Christian Cassidy is a Manitoba Historical Society council member and a proud resident of the West End. He has been writing about Winnipeg history for more than a decade on his blog, West End Dumplings.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.