Recalling the post office strike of 1918

Advertisement

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/06/2025 (188 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Winnipeg was the centre of national attention in July 1918 during Canada’s first major postal strike, which lasted 10 days and paralyzed mail service across the country.

Being a postie in the early 1900s meant low pay, little regulation of the weight of mailbags carried, and work hours that were heavily influenced by the variability of train schedules. It was also not a career, as it is estimated that 35 to 80 percent of workers, depending on the facility, were temporary.

These grievances stewed until the late stages of the First World War, when returning soldiers resumed their jobs with a new voice and willingness to fight the federal government. (The post office was a federal government department until 1981, when it was spun off into the Crown corporation known as Canada Post.)

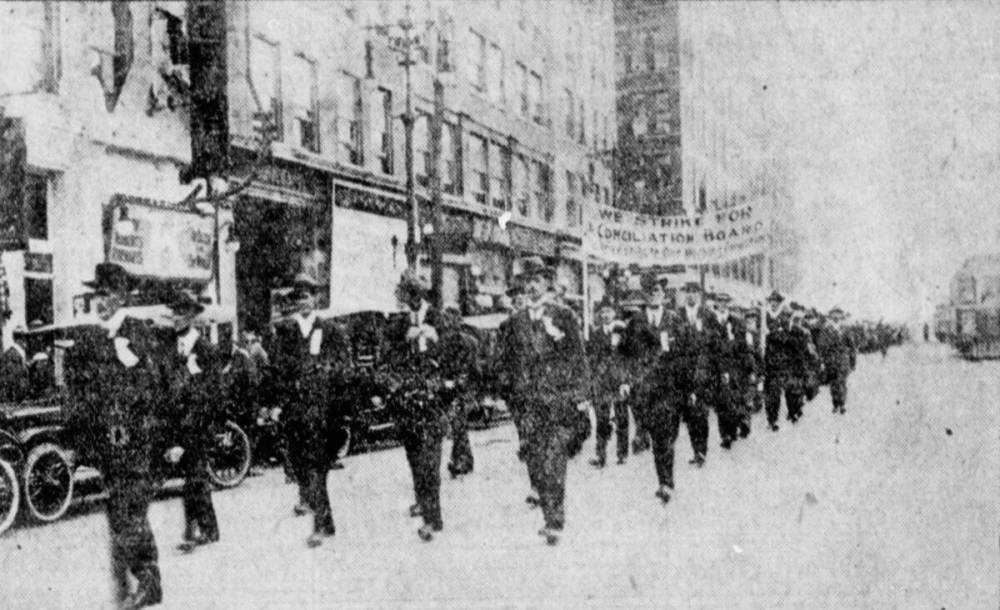

In this photo published in the Winnipeg Tribune, striking postal workers march down Main Street to a rally at the Industrial Bureau building on Friday, July 26, 1918.

Postal workers voted to walk off the job in Toronto, Winnipeg, Saskatoon, and Vancouver effective Monday, July 22, 1918. They wanted better wages and a “board of conciliation” to examine workplace conditions. They contended that a department with odd hours and many temporary workers led to poor standards and unprofessional management that needed to be overhauled.

On the morning of the strike “an apparently endless queue” of hundreds of people formed out front of the Dominion Post Office on Portage Avenue to claim any last mail from a single wicket manned by Winnipeg postmaster P. C. McIntyre

The work stoppage in Winnipeg was felt across the West as mail from eastern Canada, Europe and parts of the U.S. came through the city by train. Thanks to railway mail clerks joining the Winnipeg work stoppage, this city was the end of the line for much of that mail.

On Friday, June 26, hundreds of postal workers marched from the Ukrainian Labour Temple to the Industrial Bureau building on Main Street for a meeting and rally to explain their grievances to the public.

By all accounts, the workers had the support of the wider community. Winnipeg city council wrote to the federal labour minister asking him to meet the workers’ demands and a Winnipeg Tribune poll of MLAs showed that most felt the government was in the wrong. Even the Winnipeg Board of Trade, the city’s largest business organization, focused its attention on calling on the feds to resolve matters.

Embattled federal Labour Minister T. W. Crothers arrived in Winnipeg on July 27 to try to further negotiations. By this time, all major Western cities had joined the strike and the Trades and Labour Council warned that if matters were not resolved soon it would call on other unions to hold sympathetic strikes that could result in general strikes in many cities.

Winnipeg Free Press archives

A headline from the Monday, July 22, 1918 edition of the Manitoba Free Press.

Eventually, Crothers caved and agreed to a wage increase and to immediately dispatch Dr. W. J. Roche, head of the civil service commission, to Winnipeg to begin national hearings into workplace conditions.

On Wednesday, July 31, postal workers voted 314 to 47 in favour of the deal and were sorting mail by 7:30 pm that night. An elated postmaster McIntyre “expressed his utmost appreciation at the enthusiastic manner in which the employees returned to work.”

Christian Cassidy

Christian Cassidy is a Manitoba Historical Society council member and a proud resident of the West End. He has been writing about Winnipeg history for more than a decade on his blog, West End Dumplings.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.