‘Did You See Us?’ is a must-read

Assiniboia residential school survivors tell their stories

Advertisement

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/04/2021 (1711 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

An informative new book is ready to connect the memories of children forced into an Indian Residential school in River Heights with readers, many of whom didn’t know what was happening in their neighbourhood.

Did You See Us? Reunion, Remembrance, and Reclamation at an Urban Indian Residential School is filled with stories by survivors of the first residential high school in Manitoba, along with a foreword by Theodore Fontaine and editing by Andrew Woolford.

“It’s important that everyone remembers that we were at that school, that we were here,” Fontaine said. “People in River Heights need to know the school was there and people need to know what residential schools did to us.”

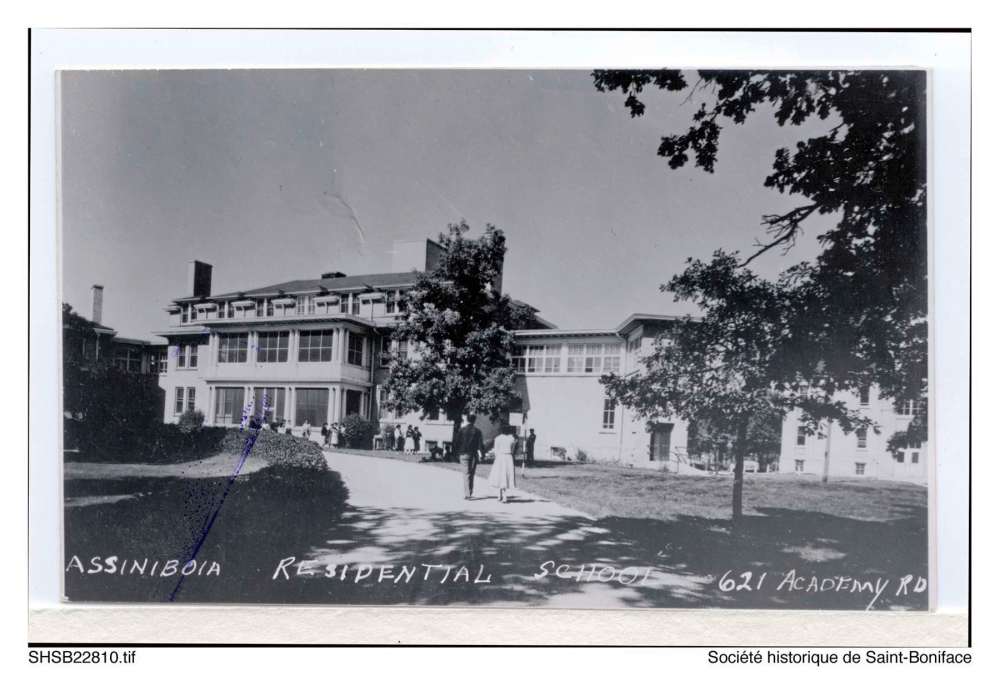

The Assiniboia Residential School was located on Academy Road near Kenaston Boulevard and operated between 1958 and 1973. The school’s dormitories were demolished in 1973 and today, the Canadian Centre for Child Protection occupies the building which once housed classrooms.

The book grew out of recorded interviews done with former students during a reunion in 2017, and also includes memories by former school staff, community residents and historians.

“The students of each era of the school experienced it differently, and we wanted the book to allow these differences to be understood,” Fontaine said, adding 300 former students from Alberta to northwestern Ontario attended that reunion.

Fontaine is a member of the Sagkeeng First Nation. He attended the Fort Alexander Indian Residential School from 1948 until 1958, and the Assiniboia Indian Residential School from 1958 to 1960. He is well-known from his work as executive director of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, and today is an author, public speaker and commentator on Indian residential schools and reconciliation.

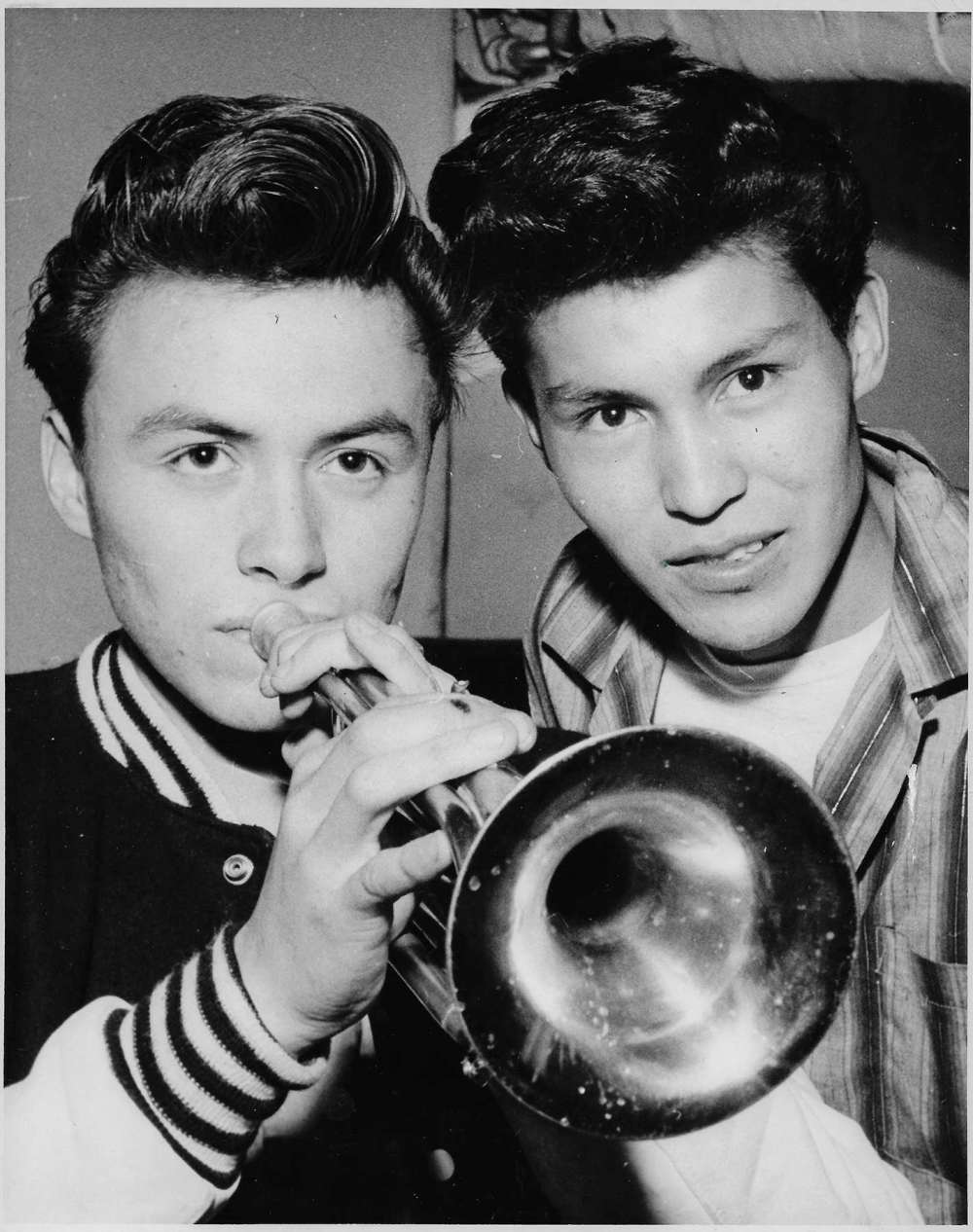

Between 1958 and 1967, Assiniboia was a fully residential school, with students living there for 10 months of the year, attending classes, sleeping in dormitories and eating together.

“Each of the 600-some students came from 80 First Nations groups, many of whom attended residential school from a young age,” said Woolford, a professor of sociology at the University of Manitoba. Woolford specializes in studying genocides, with an emphasis on the group destruction deployed against Indigenous people in North America.

The chapters proceed through the years to the last students, who were hostelled at Assiniboia while attending other high schools in Winnipeg, and moves on to remembrances from people living in River Heights, including Fontaines’ wife Morgan Sizeland Fontaine, former Winnipeg Free Press journalist Catherine Mitchell, along with the priests, nuns and teachers of the school.

“I think the school had been closed for two or three years when I visited the counselling office for kids who attended the school, and they told me the building was about to be torn down,” Fontaine said. “I located a photo from 1958. I’m in that photo. And I walked away with a burning desire to have that school’s history be known. But we weren’t at the stage we are at now in reconciliation, and so many people were scared to talk about their history.”

Today, Fontaine estimates 50 to 70 per cent of the students have departed this earth.

“It’s important we talk about how we lived,” he said, “and about what residential schools did to us. We’re all getting older, and we don’t want people to forget about us.”

Residential schools were part of a plan by the Government of Canada to assimilate Indigenous people, who were then called Indians. The institutionalization of the children, begun in 1831, was formalized in 1920 by Canada’s Parliament with the legislated mandatory removal of children from their families. The kids were locked up in Indian residential schools operating across Canada.

Fontaine said the result was a destruction of their traditional way of life, languages, culture and customs, an eradication of legal rights, governments and societies. This destruction has led to inter-generational trauma that continues today, he said.

“We have been rebuilding our culture and traditions, learning to speak our languages again. I remember a day when we were deathly scared of speaking our language,” Fontaine said. “The punishments on children were horrible. It was a shameful thing the Canadian government did to us.”

The school did produce future leaders, artists, educators, knowledge keepers, and other notable figures, including Phil Fontaine, artist Robert Houle and Senator Mary Jane MacCallum. Others were so damaged by their experiences, their lives ended in early adulthood, Fontaine said.

A book launch for Did You See Us? will be held on May 12 at McNally Robinson. For more information, see uofmpress.ca