Argyle Studio, hidden in the rough

Advertisement

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/10/2021 (1591 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s almost shocking to walk into Argyle Studio for the first time. The Dufferin Avenue building’s dull grey facade and the dim and dirty hallway leading to the studio leave you bracing yourself for grime and decrepitude.

But then you enter a room with huge red velvet curtains, behind which kicks and snares and all sorts of drums are stashed, and another wall with guitars hanging above keyboards stacked one on the other. A piano sits adorned with four plants in a neat row under soft yellow light as though cut out of a movie set’s jazz club.

Two other rooms connect to the space, both packed with mixing boards and computers with large monitors below a strip of window through which producers can see the artists they’re recording.

Granted, the studio is not exactly pristine, but it emanates a warmth that seems out of place for a warehouse in the shadow of the railyards.

It took a lot of work to get to this point.

“It was just an empty shell of a room. The ceilings were high, and nothing was here,” said Cam Loeppky, owner of the studio.

The process began two years ago, Loeppky said. He slowly chipped away at it, in between touring with Canadian rock legends Sloan, with help from family and friends.

One wall was painted with a flourish of green and yellow stripes — a band called The Lockdown did that in exchange for help, noted Rusty Matyas, a musician and producer who recently began working out of the studio.

“I think that’s a beautiful Winnipeg exchange, personally,” Matyas said.

Loeppky agreed.

Before establishing the studio, Loeppky produced music out of his house. As many have discovered in the age of remote work, it was difficult to separate his work from his home life.

“I’d wake up in the night thinking of something I had to fix,” Loeppky said, then he’d rush off to do it. “Now (I’ve) got to come all the way down here, and then do I stay here for five hours when I have just five minutes worth of work?”

Loeppky owns the studio, but there doesn’t seem to be much of a hierarchy in the social structure at Argyle Studio. It’s a small community of music makers who, at first glance, appear separated from Loeppky only by their gratitude for the workspace.

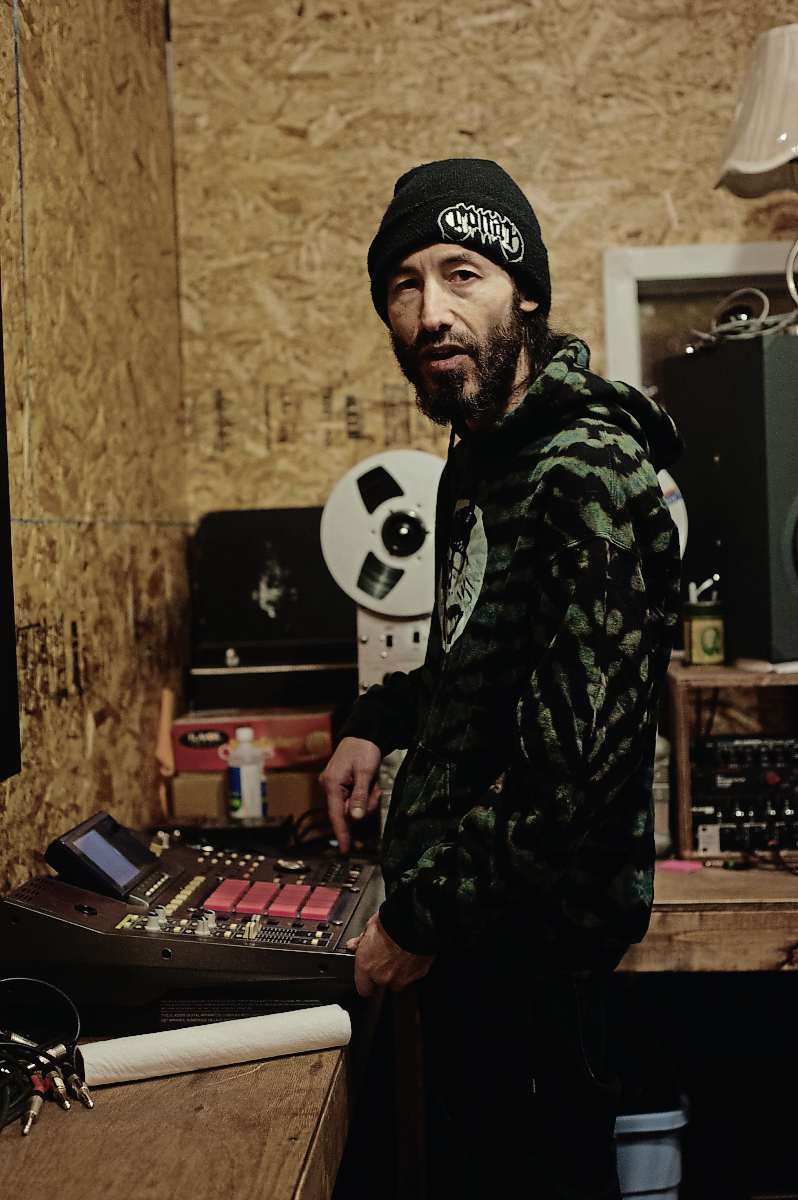

Chrys Fournier, whom Matyas and Loeppky call “Crab,” does his work in the smaller producer’s room, and the three of them call this space Argyle Lodge. This room is less finished than the others and set up for a different style of music.

Whereas Loeppky and Matyas focus on rock music, Fournier works with rap, punk and metal. Fournier said he’s been enjoying having the space to work.

“I’ve been making music and stuff for more than half my life,” he said. “But this is pretty new to me, to be working with others in a space that I’m hosting them.”

When Loeppky, Matyas and Fournier spoke, the conversation always seemed to find its way to the artists they were recording or had recorded. They gladly brought up this band whose singer was “sort of ’70s punk”; “The Clash-esque”; or that group with a kind of “afrobeat dancehall influence,” which somehow evokes an idea both vivid and vague.

Loeppky, in particular, seems uncomfortable saying what he likes about his work, saying at one point he does it just because it’s too late to change careers. But when he talks about his prized gear, like the “analog tape echo,” a grin sneaks onto his face, and it’s clear there’s at least a little something more to it.

Cody Sellar

Cody Sellar was a reporter/photographer for the Free Press Community Review.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.