|

When my daughter was born and two days later diagnosed with multiple cardiac problems who did I call for advice?

Murray Sinclair.

My wife and I had already known Murray — who died Nov. 4 at the age of 73 — for years. She was a criminal defence counsel who knew him as a lawyer and then a judge, while I knew him through my coverage of the law courts and the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry for the Free Press.

Advertisement

Why this ad? Why this ad?

Murray and his wife were guests at our wedding.

At the time of my daughter’s birth, Murray was presiding over the pediatric cardiac surgery inquest following the deaths of 12 babies and children who had undergone cardiac surgery at the Children’s Hospital in 1994. The inquest took five years and resulted in the closure of the surgical program in Winnipeg, with most children subsequently sent to either Edmonton or Toronto.

But those recommendations were still in the future when I called Murray.

We had just received our daughter’s diagnosis from one of the main cardiologists connected with the ill-fated surgical program and who had already testified in the inquiry. To say we were nervous is an understatement.

With no surgical program in Winnipeg, we were asked where we wanted our daughter to go: Montreal, Toronto, Saskatoon, Edmonton or Vancouver?

We chose Toronto — the Hospital for Sick Children had a stellar reputation here and around the world. But we still wanted to check with Murray. Who else would have the most up-to-date expertise?

Murray, of course, empathized with our situation and said he would be thinking of us. He advised that for our daughter’s needs Sick Kids would be the best place to go. But he also said Saskatoon had a phenomenal surgeon too.

We went to Toronto. Mary survived — in fact, she went on to have three more surgeries there — and is now 27.

A few years before that, after months of my wife regaling me with stories about what it was like to bring justice to the fly-in court circuits for communities on the east side of Lake Winnipeg, I put in a media request to join the court party so I could do a story.

The Canada Life Centre will host the memorial service for Murray Sinclair, starting at 2 p.m. Sunday. (Mikaela MacKenzie / Free Press files)

Murray was the judge who called saying I could come report on his court in a few weeks time. He wanted me to see how an Indigenous judge could deal with matters in these communities.

He also laughed uproariously when I surprised my wife and told her I wasn’t just dropping her off at the airport that morning.

They were two long days. An early morning flight, followed by a short boat ride across the lake from the airport to the community hall in Little Grand Rapids First Nation, where court was held. At dusk, we took another boat ride across the lake to the lodge. The next day, another early morning flight, this time on a float plane to Pauingassi First Nation.

After dinner the evening in between, Murray told my wife and I (we had only been married a few months at that point): “You guys don’t know anything about love. You think you know about love? You’ve still got a lot to learn.”

We all laughed. Turns out Murray was right, as we’ve been learning over the years since then.

Not long after, and for the first and only time, Murray called me about a story I might be interested in covering.

He was going to Hollow Water First Nation to hold the very first sentencing circle for an Indigenous man charged with a crime. Instead of a formal court process, in a court room with the judge at front, prosecution and defence attorneys across the room from each other, this was literally a circle of community members in a hall. Everyone had an equal place, whether it was the judge, lawyers, accused, victim, her family members or regular folk from the community.

In the end, the community decided the offender would have to serve three years of probation at the reserve, all under the watchful eyes of residents who vowed to keep tabs on him.

It ran until very late at night and Murray decided to stay behind with the community while I ventured back into the February night for the long ride back to Winnipeg — in a Free Press car with an engine that decided to seize up completely on the way back, thankfully in sight of Lockport.

But it was one of those proceedings where you could see reconciliation in action in front of you — long before that word became etched into the national consciousness, with Murray once again leading the way for the province.

Murray even volunteered to help my eldest daughter, who was volunteering a few years ago at Katimivik, set up a video chat with him about Truth and Reconciliation for the young adults in their Quebec City residence. It ended up growing from a talk with just with her fellow volunteers into a national conversation with all the organization’s young volunteers participating. Murray had no problem with the change.

“Where’s my friend Sarah?” he said to a screen filled with volunteers in their 20s until he spotted her waving.

The last time I spoke with Murray was earlier this year. Out of the blue, instead of me calling him for comment on a story, he called me for what turned out to just be a chat. Our final chat.

Murray and his wife had moved out of their house north of the city into what he described as a senior’s living residence. He did say he still had the house — with a garage full of files, which he would have to go through to see what was garbage, what was worth keeping and what should be offered to the provincial archives.

Murray also said we would all have to get together soon and I said yes, we should.

Sadly, we are still having to isolate because of our youngest daughter so could never firm up those plans. Not much later his wife Katherine died. And soon after that, he was in hospital himself.

It’s sad to know that Murray is no longer a phone call or visit away — not only to seek advice or get comment for a story, but also for friendship.

Murray was there for my family when I needed help with a little baby who had a heart that needed fixing.

Miigwech Murray.

How they lived

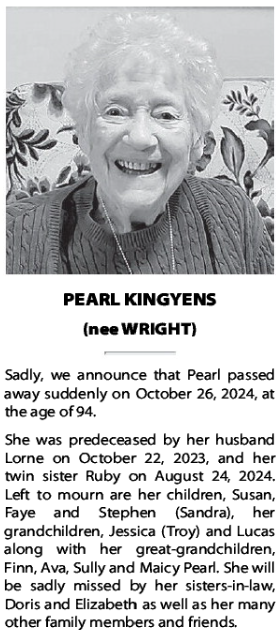

It wasn’t Cupid’s arrow but an errant dart that brought Pearl Kingyens and husband together.

Pearl, who was 94 when she died on Oct. 26, happened to be in an English pub in 1952 when Lorne nearly hit her with a dart.

They were married two years later and moved to Canada, where she became a military wife, packing and moving several times, until finally settling in Winnipeg.

Pearl was a busy volunteer; especially at the Grace Hospital, where she helped for 25 years.

Read more about Pearl.

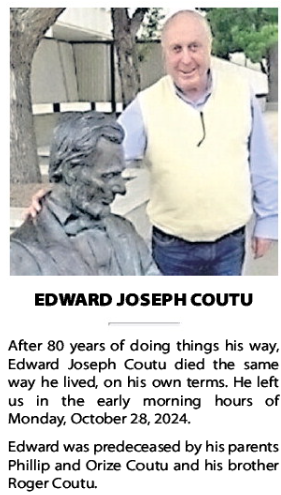

Ed Coutu was the assistant to Defence Minister James Richardson before he decided to buy his family funeral business in 1977.

Ed, who died on Oct. 28 at 80, expanded the operation to become the largest family-owned funeral business in Western Canada before selling it in 1995.

Five years later, with a non-competition clause expired, Ed returned to the industry and opened E.J. Coutu funeral home with his son.

Read more about Ed.

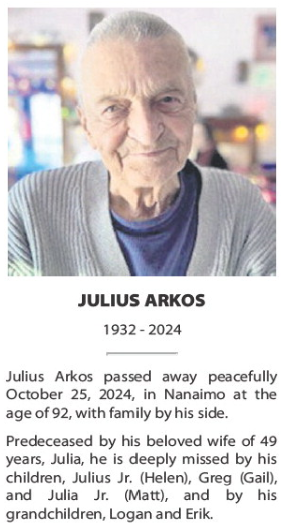

Julius Arkos and his wife fled Hungary and left their careers behind.

Julius, who was 92 when he died on Oct. 25, had worked in theatre, film and TV while his wife was a ballerina and artistic director.

To make a better future for their first-born son and future children, the family came to Winnipeg, where Julius worked at CN Rail until retiring.

Read more about Julius.

A Life’s Story

Grace Eiko Thomson was a voice for Japanese-Canadian culture after experiencing injustice in her childhood.

Grace, who died on July 11, was living in British Columbia with her family when the Canadian government authorized the removal of all persons of Japanese origin from the restricted zone on the West coast. The family was taken to an internment camp in the interior, where they stayed until moving to Manitoba in 1945.

Grace Eiko Thomson believed she had an obligation to stand up against injustice in the Japanese-Canadian community and beyond. (Supplied)

Grace became a historian, teacher and writer who dedicated her life to shining a light on the dark period in Canada’s history which her family — and many others — experienced.

“Through hard work and determination, she powered through to fight discrimination, misogynies, narrow-mindedness and criticism along the way,” said her younger sister Keiko Miki. “She was resilient.

“She used her own experiences to teach others it was okay to speak up.”

Read more about Grace’s life.

Until next time, I hope you continue to write your own life’s story.

|