Risk and reward Frigid and feisty, the first Grey Cup in Winnipeg was also a financial coup

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/09/2021 (1577 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

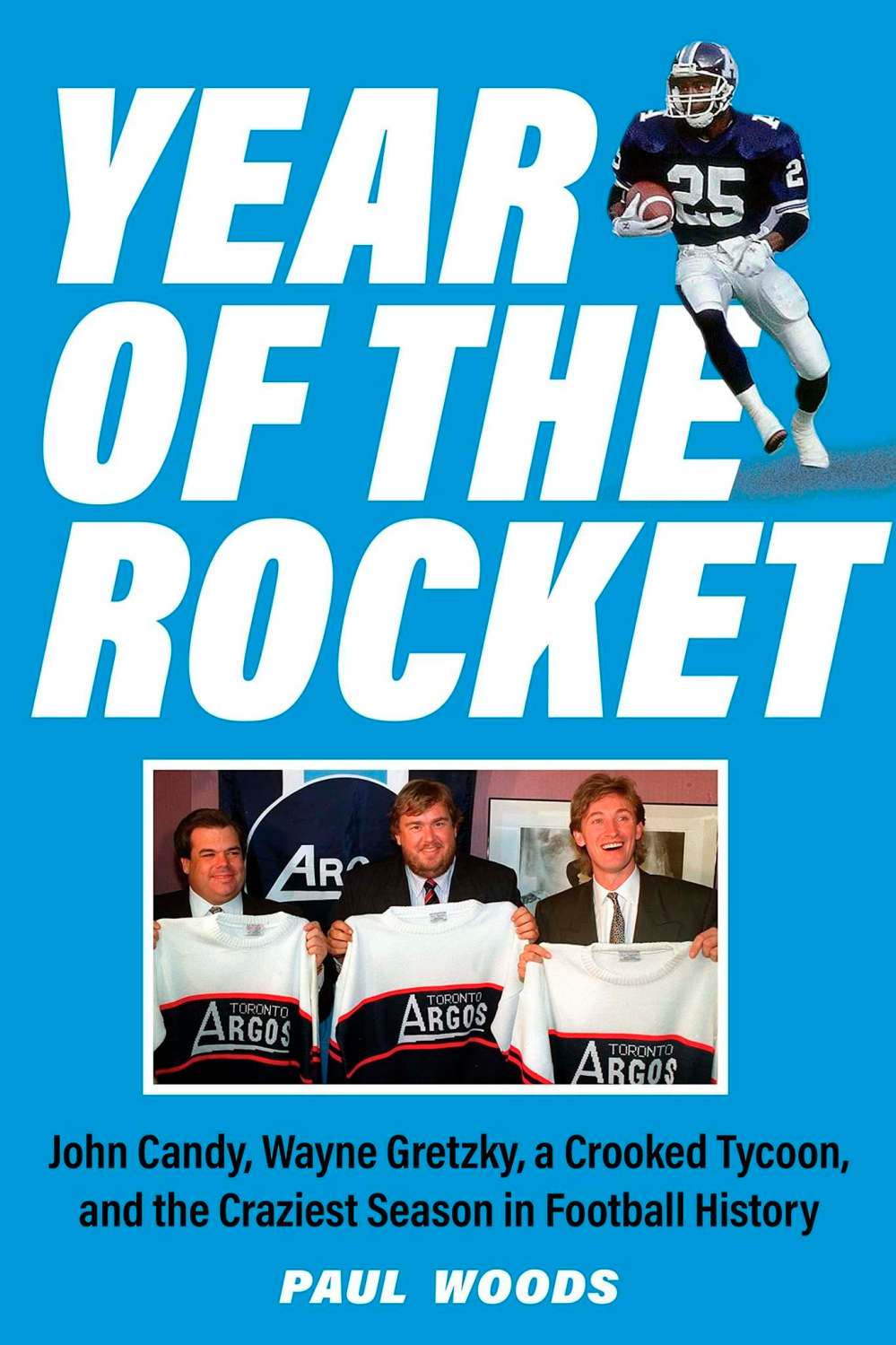

The book Year of the Rocket: John Candy, Wayne Gretzky, a Crooked Tycoon, and the Craziest Season in Football History, by journalist and Canadian football historian Paul Woods, tells the story of one of the biggest gambles in the history of professional sports when, in 1991, the unlikely trio of hockey legend Wayne Gretzky, actor John Candy and Bruce McNall, an on-the-rise sports executive who would subsequently have a dramatic fall from grace, acquired the CFL’s Toronto Argonauts and lured north one of U.S. college football’s brightest prospects, Raghib ‘Rocket’ Ismail, with the richest gridiron contract ever, at the time.

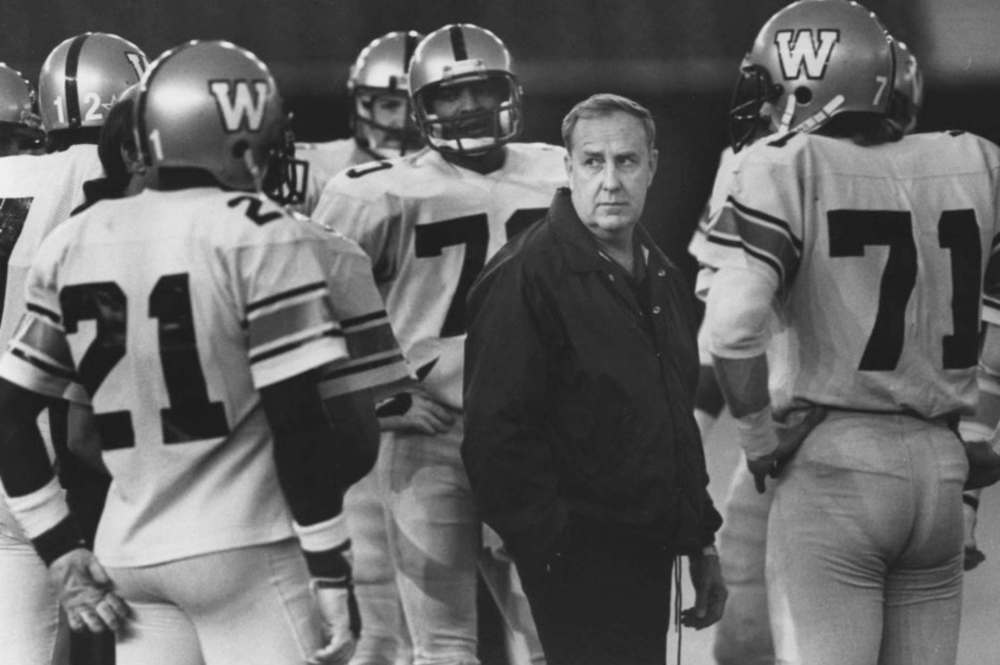

But that wasn’t the only gamble of 1991. Winnipeg Blue Bombers general manager, Cal Murphy, and Winnipeg Football Club, the not-for-profit entity that owns the team, took a financial leap of faith to bring the Grey Cup final to Winnipeg for the first time.

The following is an excerpt from Year of the Rocket, published by Sutherland House. It was officially released Sept. 1.

Cal Murphy had a dream. The general manager of the Winnipeg Blue Bombers longed for his city to stage the Grey Cup.

The CFL had traditionally rotated the game among its three largest cities — Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver — and played it in smaller centres only on rare occasions. But Murphy thought Winnipeg deserved a shot, especially now that Montreal was out of the league. If the Bombers could replace the Alouettes in the CFL East, why not as a Grey Cup host, too?

Harry Ornest, still the owner of the Argos in 1989, considered the notion of staging the league’s showpiece event outdoors in Winnipeg’s 33,000-seat stadium ridiculous. A native of Edmonton, Harry O knew how cold it can get on the Prairies at the end of November. Why risk the elements when the league could play its final indoors in Vancouver, at 60,000-seat B.C. Place Stadium? Or at Toronto’s new SkyDome with its retractable roof and 54,000 seats? Everyone would be comfortable, and the CFL would maximize its revenue.

But Murphy wasn’t one to give up easily, and he had an argument that was difficult to refute. Every other city except tiny Regina had staged the Grey Cup: Ottawa (1967 and ‘88), Hamilton (1972), Calgary (1975) and Edmonton (1984). It was finally Winnipeg’s turn, Murphy maintained. Besides, the Grey Cups in Edmonton and Calgary had been played in extremely chilly conditions, without any real problems. A woman even ran onto the field naked during the opening ceremony in Calgary — how uncomfortable could it have been?

And so the CFL awarded Winnipeg the 1991 Grey Cup, conditionally, early in 1989. Ornest, who had just joined the league’s board of governors as new owner of the Argonauts, immediately began working behind the scenes to get the decision overturned. “Unless they fulfil a financial commitment which will equal the revenues that we can generate in the SkyDome or in Vancouver, they won’t get the votes,” he predicted.

Murphy, naturally, fought back and, unlike the newcomer Ornest, he had a lot of support around the league, especially in his fellow Prairie city, Regina. A savvy political operator, he rallied the governors around a mutual suspicion of Canada’s largest city. “Somebody in Toronto is looking at his own interest,” he said.

When it came to the final vote, Murphy triumphed. Winnipeg would host the 1991 Grey Cup.

While thrilled that his city would be Canada’s centre of attention for one day, Murphy lamented that Winnipeg Football Club (the not-for-profit entity that owned the Bombers) would get nothing itself out of the Grey Cup. Revenue would flow to the league, even though most tickets would be sold in the Manitoba capital. He and Ken Houssin, the Blue Bombers’ treasurer, discussed this one day over lunch at Rae and Jerry’s Steak House.

“You know this thing is going to sell out,” Murphy said. “I’m convinced of it.”

“What we should do,” Houssin replied, “is buy all the tickets and scalp them.”

It was said as a joke. But Murphy, whose traditionalist nature had made him one of the last holdouts against signing other teams’ free agents or allowing female journalists into locker rooms, seized on it as an idea that might actually work. What if the Bombers bought all the tickets from the CFL (including 19,000 for benches erected temporarily in the end zones), then sold them for higher prices? The league would get guaranteed revenue, and the Bombers could turn a profit.

Rough calculations suggested there was potential to clear up to $4 million in ticket sales, even after other costs were factored in. If the league agreed to sell the 50,000 seats for $3 million, the football club could wipe out much of its million-dollar debt.

The club’s executive embraced the concept, and the league was game to try it as well. But there was one big hurdle. The Bombers would have to take on all the risk. A team “owned” by hundreds of community members, and already in debt, could dig a deeper hole for itself. Furthermore, the club didn’t have the money to pay up front for the tickets, and no bank was interested in floating a loan for so uncertain a venture.

Murphy came up with another creative idea: ask Winnipeg Enterprises Corporation, the municipal agency that operated the city’s football stadium, to guarantee the payment to the league. The initial answer was no.

Houssin pleaded with WEC representatives: “This is a tragedy. We’re going to leave a million dollars on the table, which we really need.”

Murphy, Houssin, and other executives pushed hard, offering the corporation parking revenue and a big portion of food and drink revenue from the game. In the end, WEC agreed. The 1991 Grey Cup game would be staged for the first time with a revenue guarantee to the league, and the potential for profit (or loss) shifted to the host city.

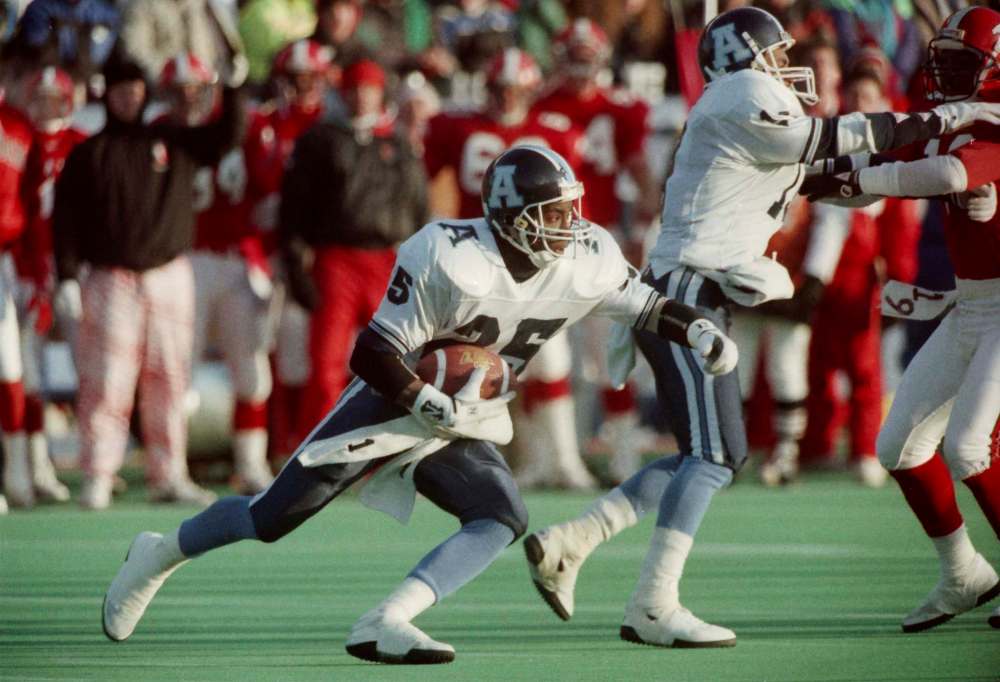

As expected, the vast majority of tickets, which cost $107 in the grandstands and $70 in the end-zone bleachers, were sold in and around Winnipeg. That was the good news. The bad news was that the defending champion Blue Bombers were crushed by the Argonauts in the Eastern Final, and Winnipeg lost the chance to watch its team play the Grey Cup at home.

When the Argos arrived in town on Tuesday during Grey Cup week, they discovered that virtually everyone in town was against them. Usually, a host city will support its divisional representative in the final, but Winnipeg had never truly felt like an Eastern team, and the city had learned to hate the Argos since joining the division. Winnipeggers weren’t especially partial to the Western representative, the Calgary Stampeders, either, but the Alberta team was easier to cheer for than a bunch of big-name Hollywood types trying to buy a championship by signing Rocket Ismail to a huge contract.

Argo fan club members who walked in the Grey Cup parade the day before the game were pelted with garbage. “Old women were coming up and spitting on us,” says Lori Bursey, who led a contingent of five dozen Argo boosters to Winnipeg. “I’ve never seen so much venom coming from any city. They were just nasty.”

At that parade, and in hotel lobbies around town, a chant was heard frequently. “I don’t know but I’ve been told. Rocket is afraid of the cold.”

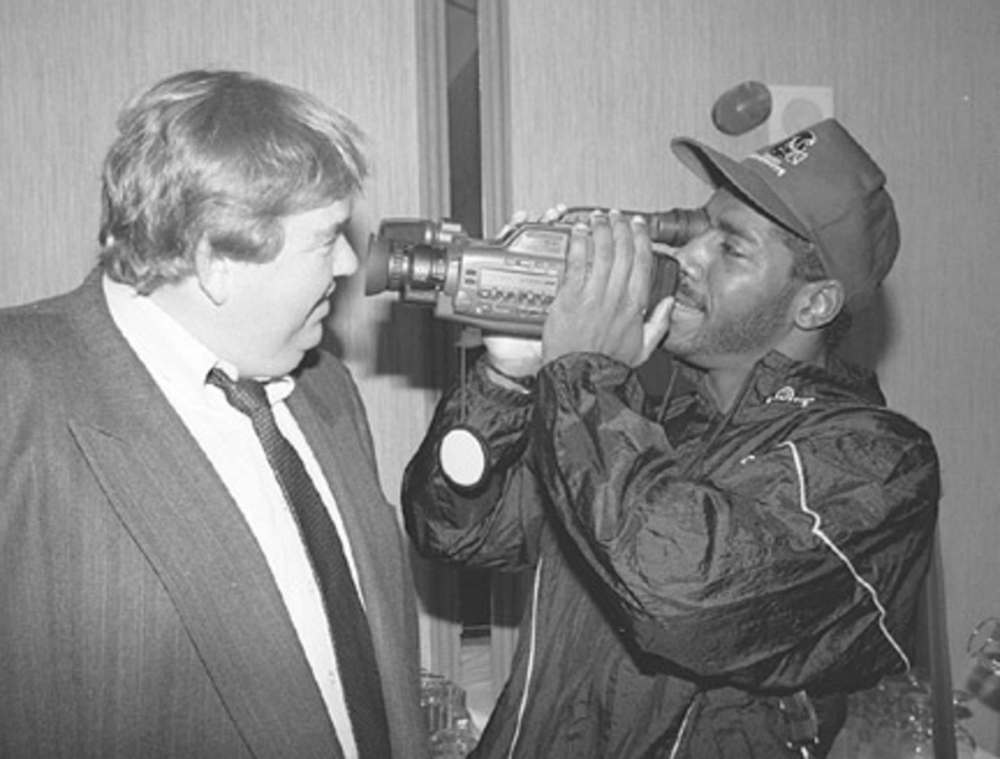

The only thing that kept anti-Argo sentiment in Winnipeg from unanimity was the presence of the one person even the most ardent Toronto hater couldn’t get mad at: John Candy.

While his co-owners Bruce McNall and Wayne Gretzky didn’t arrive in town until game day, the popular actor made the rounds all week. He hosted relatives and friends at Alycia’s restaurant, and frequented the Palomino Club, the scene of the week’s most raucous Grey Cup parties.

Candy at first tried to party inconspicuously at the Palomino, sometimes called the Palimony because of its reputation for debauchery, with friends like CBC’s Brian Williams and actress Cynthia Dale. “We’ll come in through the back door, enter through the kitchen because I don’t want to create a scene,” he told them. But being seated in a roped-off area couldn’t stop one of the world’s most recognizable humans from being spotted, and Candy’s generosity didn’t help matters.

“Buy the house a round,” he said to a Palomino server. The club’s manager came over to make certain he knew what he was doing: “Mr. Candy, there’s 600 people here.”

“Then you better hurry,” Candy replied.

The disc jockey got on the mic: “John Candy just bought the house a round.”

The place erupted, and Candy kept the party going all week.

“I don’t think he slept,” says Williams.

Argo players were overjoyed to be assigned to the Winnipeg Stadium locker room normally used by the Bombers. Some players raced to claim the lockers that ordinarily belonged to motormouth Tyrone Jones and his linebacking partner, James West. “There was nothing we could do about it,” says West. “We would have done the same thing.”

Some Bombers took part in festivities during Grey Cup week. Not West or Jones. “We were distraught. We didn’t hang out; we didn’t go anywhere. We were watching TV and looking at all the celebrations and what was going on in the city, and we were in a bad state of mind.”

(Jones and West did attend the Grey Cup, with sideline passes. Jones trash-talked the Argos constantly, until league officials told Bombers GM Murphy to get the pair off the field.)

When she learned the Grey Cup was going to be played in Winnipeg, Suzan Waks was aghast. “Open air? In the middle of winter? In Winnipeg?”

Waks, a senior executive in McNall’s empire who often represented the Argonauts at CFL meetings, was part of the group that boarded the Los Angeles Kings’ jet for an early-morning flight to Winnipeg on Grey Cup Sunday. With her were McNall, Gretzky, family members, team executives, and a handful of celebrities, including actors Martin Short and Alan Thicke. Some were not dressed appropriately for a game to be played in temperatures well below zero.

“I don’t know but I’ve been told. Rocket is afraid of the cold.”– A crowd chant from the Grey Cup parade

One of them, Rod Martin, a retired Oakland Raider, showed up at the airport in jeans, shoes, no socks, and a light jacket. “Rod, we’re going to Winnipeg,” said Argos executive Roy Mlakar, who knew Martin from pickup basketball.

“I played on a frozen tundra field” in the NFL, Martin scoffed. “What do you mean, cold?”

Five hours later, the pilot got on the intercom as the booze-soaked jet made its final approach into Winnipeg. It was 70 degrees Fahrenheit in L.A., he said, and minus-30 at their destination. “We have a 100-degree swing.”

After landing, the group boarded limos for Winnipeg Stadium. They saw people streaming towards the facility in thick parkas, snowmobile suits, heavy boots, and balaclavas. “Dressed like it’s Alaska,” Waks recalls. Many were clutching slabs of Styrofoam or cardboard, to be placed under their rear ends or feet to insulate against the cold.

Someone had set up comfortably heated trailers at field level for use by bigwigs. Martin, who had “played on a frozen tundra field,” ensconced himself in one of these after ten minutes, and never left.

McNall, wearing a leather coat and a big toque, went back and forth between the trailers and the field. “I have no idea how the players could play,” he says. “I had no clue as to what cold was.”

“The gloves I had, I might as well not have worn any gloves because they didn’t do anything at all. I thought, who watches football in the wintertime, with this cold?”– Diane Lee, future wife of Argo star Pinball Clemons

Candy and Gretzky, having grown up in Canada, were dressed appropriately for the conditions. Standing on the sideline, they also added liquid insulation. Candy approached Argo head coach Adam Rita, who looked like the Michelin man in a heavy parka, balaclava and toque.

“Coach, you look pretty cold,” Candy said. “You want some coffee?” He opened his coat to reveal a flask of alcohol. “I’ve got some anti-freeze in here.”

Rita declined. “John, I’ve got to coach this game.”

Some Argo fans from Toronto, who perhaps should have known better, were also underdressed. Bursey recalls showing up to the game in her “little Toronto fashion boots and this little, short jacket.” A fanatic who seldom misses a play, she seriously considered returning to her hotel during the game. “At halftime, I can barely move. I’m crying. I didn’t know it could get that cold. I had no idea.”

Bursey took her “fashion boots” off in a bathroom and attempted to warm her feet under an electric hand dryer. Another who tried that was Diane Lee, the future wife of Argo star Pinball Clemons; she had flown up from her home in Florida. Her feet were stinging. “You didn’t want to put your shoes back on because you knew it would hurt. The gloves I had, I might as well not have worn any gloves because they didn’t do anything at all. I thought, who watches football in the wintertime, with this cold?”

If watching was tough, especially for those unprepared for the deep freeze, playing was something else altogether.

Had the game been played a week earlier, conditions would have been unseasonably pleasant. It was a relatively balmy five degrees Celsius (41 Fahrenheit) on the Monday before the game. But a cold front moved into southern Manitoba, and it got colder and colder as the week went on.

Some Argonauts practised in shorts, determined to show that even though they played home games in a climate-controlled dome, they were not afraid of bad weather. Brian Warren and Darrell K. Smith posed with bare chests for a newspaper photo, saying, “We’re ready to fight butt naked.”

By game day, however, even tough, normally bare-armed offensive linemen were trying to minimize their exposure. Receiver David Williams recalls peeking at the field before kickoff. There was nobody warming up. “That’s when you know it’s cold, when there’s no player on either team on the field.”

When players were instructed to warm up, says cornerback Ed Berry, “I ran out and ran right back into the locker room. ‘I’m good! I’ll stretch in here.’”

At times it seemed there were two games happening at once. Argos versus Stampeders, and both teams versus the cold. The sun shone brightly for most of the game (the last Grey Cup played in daylight hours), but the Argo sideline was on the shady west side of the stadium. Calgary coach Wally Buono “must have been a good Christian because he sat in the sun all day,” says Rita. “I was in the shade freezing my butt off.”

Large propane heaters were installed on the sidelines. Many players quickly deduced they were better off staying away from them. “As soon as you pulled away from it, it felt like your hands were frozen solid,” says Berry.

Ball boys found a use for the heaters: to thaw bottles of water and Gatorade that otherwise froze solid almost instantly.

Equipment staff had about ten seconds to adjust shoulder pads before their fingers went numb. Helmets would freeze if removed, and become difficult to put back on.

Every time Matt Dunigan took his helmet off on the sideline, the protective air bladder inside would burst. He wouldn’t realize it and would return to the field without the added layer of air for protection. Finally, equipment manager Danny Webb instructed him to leave his helmet on at all times.

That wasn’t the only problem with Dunigan’s helmet. On one of the hits he took, his head hit the turf and the helmet cracked open. He would end the game wearing a spare helmet normally assigned to reserve running back Paul Palmer.

Players quickly discovered that playing on frozen artificial turf was like playing on concrete. “It felt like you fell from 20 feet when you hit the ground,” says receiver David Williams.

They also found it difficult to understand coaches’ instructions. “Their faces were frozen,” says receiver Paul Masotti. “They couldn’t move their mouths like they normally would.”

“You almost couldn’t function,” says offensive tackle Kelvin Pruenster. “Neurologically, you weren’t connected to your legs.”

In addition to multiple layers of undergarments, some players slathered Vaseline petroleum jelly on their faces and arms to prevent their skin from cracking. Many had wrapped their ankles and wrists loosely, fearing they might cut off circulation if the tape was too tight.

“You ask yourself, ‘Was it worth it?’ Honestly, I felt it would have been. But thank God they didn’t have to amputate one or two toes.”– Cornerback Reggie Pleasant

The concern was well-founded. Cornerback Reggie Pleasant, who always tied his shoelaces tightly to prevent his feet from sliding around inside his cleats, would end up with severe frostbite. He was too numb to notice during the game, but in the locker room afterwards, Pleasant’s thawing feet “were purple and swollen. Excruciating pain. Believe it or not, there was talk of amputation — a toe or two.” It took a couple of months for Pleasant to recover, and he had tingling sensations in his feet for a long time after that.

“You ask yourself, ‘Was it worth it?’ Honestly, I felt it would have been. But thank God they didn’t have to amputate one or two toes.”

On the CBC telecast, announcer Don Wittman, a Winnipegger himself, naturally mentioned the conditions. It was minus-17.5 Celsius at kickoff, with 13-kilometre-an-hour winds. On the scale used in 1991, that created a wind chill of 1,400 watts per square metre. In today’s scale, that would be expressed as wind chill of about minus-25 C.

Wittman updated viewers about the temperature throughout the game. Watching at home, countless Winnipeggers, sensitive about the habitability of their city, screamed at him to shut up. “The people in Winnipeg went nuts,” says Brian Williams, who hosted CBC’s pre-game coverage. “‘How can you say that? You’re one of us!’”

Despite the monstrous wind chill, 51,985 hearty souls had packed into Winnipeg Stadium. More than a third of them squeezed together on temporary metal benches in the end zones.

The contrast between the enthusiastic sellout crowd and the previous year’s Grey Cup was stark. Despite Ornest’s belief that only the big cities could provide a revenue bonanza, the 1990 game in Vancouver had been a disaster, with thousands of empty seats. The league’s eight teams came away with just $145,000 each from gate receipts. In 1991, teams received $375,000 each from the $3 million sent to the league.

Organizers in Winnipeg had succeeded in doing what Murphy and Houssin believed possible. They had made money “scalping” tickets, and used it to pay down the Blue Bombers’ debt.

They had also done something else, which few were able to foresee at the time. The league inadvertently discovered the value of playing the game outdoors in cities where it meant the most, and where there was less competition for attention. It may have been freezing, but the enthusiasm of Winnipeggers for the Grey Cup was palpable. Everyone in town was caught up in football fever. “This is the soul of the CFL,” Grey Cup committee chair Art Mauro said after the game. “It’s not in Toronto or Vancouver. [In smaller cities] we feel strongly about this national event.

It’s not just a football game; it’s part of the fabric of Canada.”

A year later, the Grey Cup would return to SkyDome, with the Argonauts hoping for big profits. There was virtually no buzz in Toronto about the game, and ticket sales were so challenging that the Argos were only too happy to cede the rights to the 1993 game to Calgary. By 1995, the final had even been played in little Regina, and over the past 25 years it has gone to “small cities” 16 times, including three more games in Winnipeg. Far from ruining the Grey Cup, the small markets breathed new life into it and, surprisingly, earned more revenue.

Cal Murphy, who died in 2012, the year of the Grey Cup’s centennial, would be proud.