Sculpting stories No longer able to carve, Omalluq Oshutsiaq turned to portraying her past on paper

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/05/2024 (573 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For most of her career, Omalluq Oshutsiaq was a carver.

Not only a carver, but an artist of international renown, one of the few female carvers from Kinngait, Nunavut, (formerly Cape Dorset) to garner such recognition.

art preview

Omalluq: Pictures from my Life

● Curated by Darlene Coward Wight

● WAG-Qaumajuq, Giizhig Gallery

● On view until March 2025

Oshutsiaq, who was born in 1948, loved to carve women — women working, women supporting other women in labour, women giving birth.

And then, in the 1990s, she severed a tendon in her wrist with an electric grinder, effectively ending her carving career.

But in 2013, at the encouragement of Bill Ritchie, then the director of Kinngait Studios, Oshutsiaq began to draw. With coloured pencils, she created vivid, hyper-detailed depictions of her everyday northern life, her childhood memories, as well as Inuit legends and stories. Through art, she processed the 2012 death of her husband and the loss of her ability to carve.

She spent the last year of her life putting it all down on the page. Oshutsiaq died from cancer in 2014 at age 66.

In 2015, Darlene Coward Wight, curator of Inuit art at WAG-Qaumajuq, was visiting Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto, where she made an exciting discovery: a whole cache of Oshutsiaq’s drawings.

BROOK JONES / FREE PRESS Darlene Coward Wight is the curator of Omalluq: Pictures from my Life, which features work by the late Kinngait artist Omalluq Oshutsiaq.

“And I was so excited by them,” she says. “They were just beautiful. The detail, the information that she reveals in the drawings. And I just said, ‘We’ve got to have these for the gallery.’

“So I bought all 19 of them, right then and there.”

Those 19 drawings compose Omalluq: Pictures From my Life, curated by Wight and on view now in the Giizhig Gallery at WAG-Qaumajuq. It’s the most significant collection of Oshutsiaq’s work, which invites the viewer to linger.

“The more I look at her things, the more I discover details that reveal all kinds of history,” Wight says.

In Store items I remember from 1950s, Oshutsiaq has assembled a still life of brightly coloured boxes, tins and bags — Manitoba Sugar, Fort Garry Tea, some sticks of Wrigley’s Doublemint, Klim powdered milk — that offers both insight into what life in northern communities was like at the time (what was hard to get, what was a treat), as well as how those iconic labels (now collector’s items in many cases) imprint on a child’s brain.

Collection of Winnipeg Art Gallery Untitled (Kananginak Carving), 2013

Untitled (Kananginak Carving), meanwhile, is another childhood memory: a carver works outside while a pigtailed little girl — possibly little Omalluq — looks on through the window.

“It’s a typical scene as you walk through Kinngait, as I’ve done a number of times; you see carvers outside making their stone carvings because it’s too dusty to do it inside,” Wight says.

But Oshutsiaq’s tremendous eye for detail goes beyond depicting the familiar.

“I got looking at this and I recognized the carver: I thought, ‘That’s Kananginak Pootoogook,’” Wight says. “And he’s carving a musk oxen that is just like one that we have in our collection.”

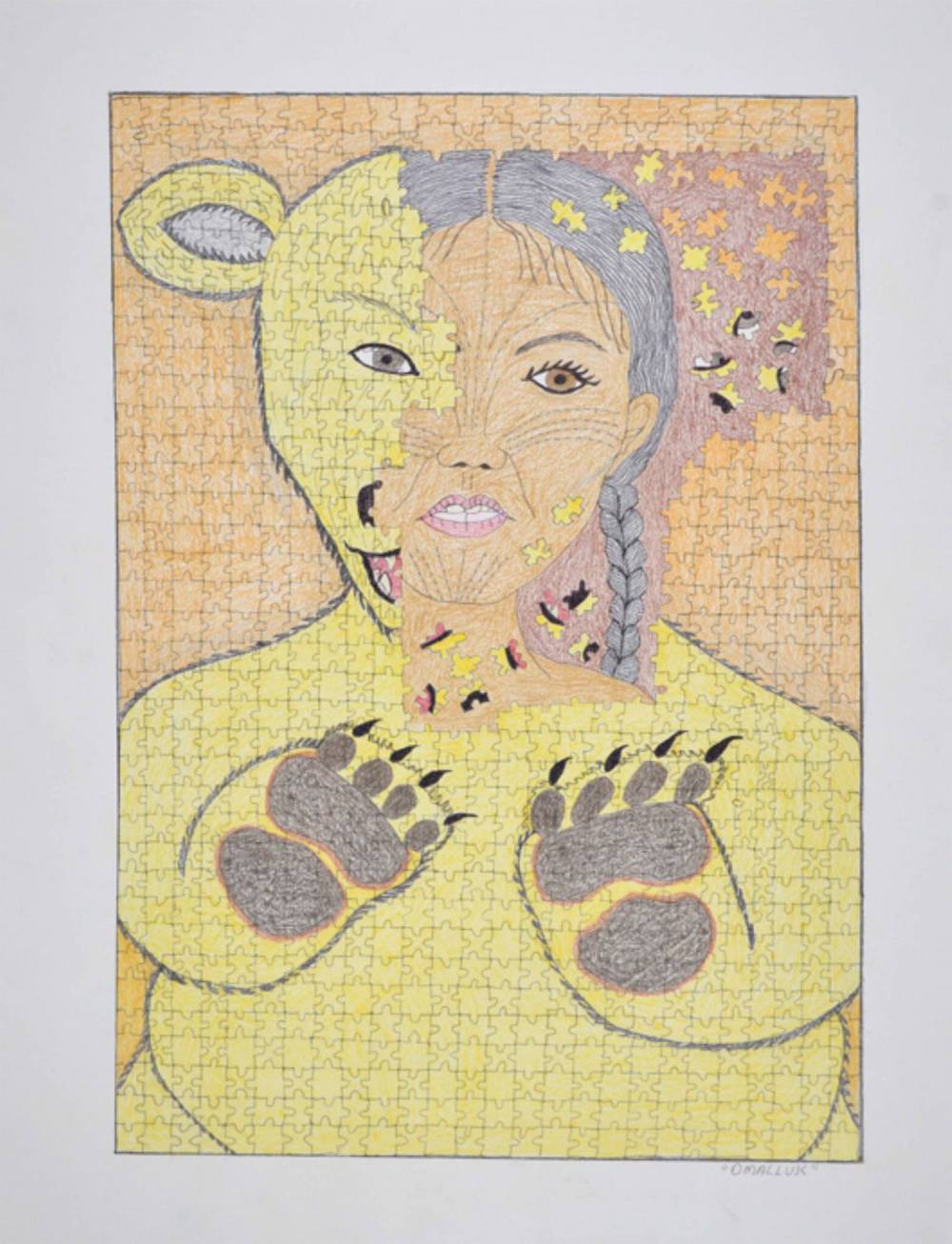

Collection of Winnipeg Art Gallery Untitled (Shaman’s Transformation), 2013

Oshutsiaq also had a talent for telling traditional stories in bold new ways, as in Untitled (Shaman’s Transformation), in which a woman with grey plaits and a tattooed face is turning into bear.

“This phenomenon of transforming into the form of your helping spirit, which in this case is a bear, is very seminal to Inuit shamanism — the belief you can take on your helping spirit’s form, you can take on their abilities,” Wight explains.

“But rather than just showing it the way artists often show it as a transformation piece, she’s showing the transformation happening as a jigsaw puzzle over top of the woman’s face. I’ve never seen that before.”

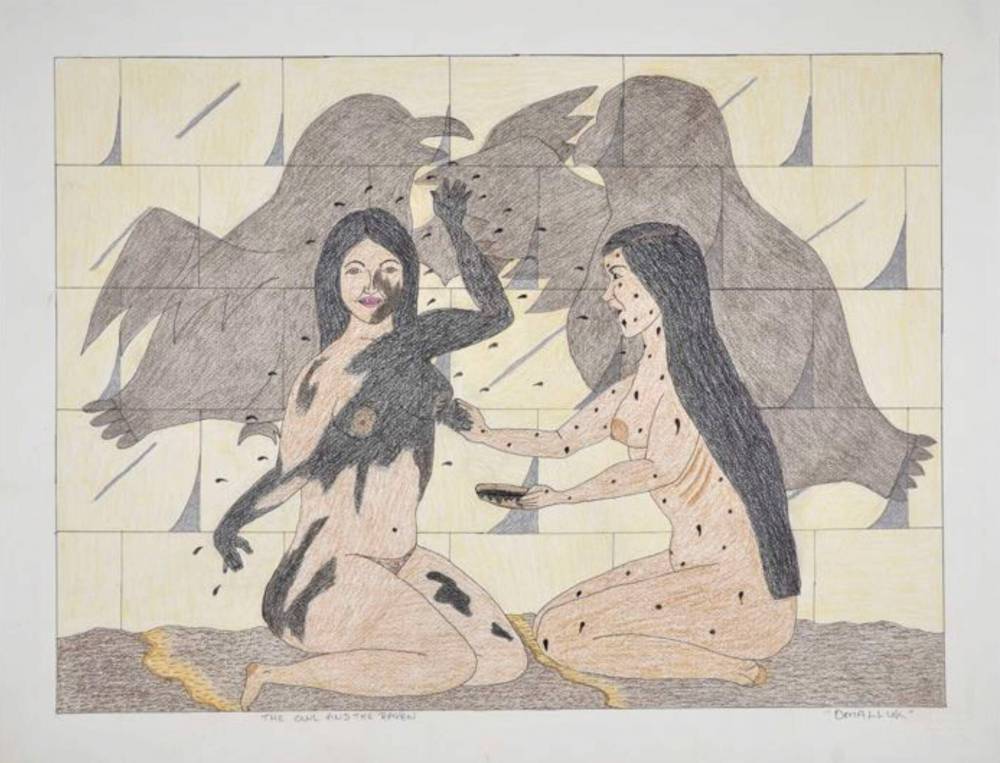

The Owl and the Raven is similarly innovative. The drawing depicts the title Inuit legend, in which Raven decorates Owl with spots — à la the Snowy Owl — but when Owl attempts to return the favour, Raven won’t stay still.

“Finally, she gets frustrated and dumps her lamp with the soot all over the raven, and that’s why the raven is black to this day,” Wight says.

Owl and Raven are usually shown as, well, an owl and a raven — including in the charming 1973 stop-motion animated National Film Board short that uses seal fur puppets. In Oshutsiaq’s hands, however, the birds are represented by arguing shadows on the wall and Owl and Raven are depicted as laughing women, Owl playfully painting Raven’s body, who is in turn getting spots all over Owl.

Collection of Winnipeg Art Gallery The Owl and the Raven

“Oh my gosh, the number of times I’ve seen artists do this story, but I’ve never seen it done this way,” Wight says.

Oshutsiaq’s body of work is proof it’s never too late to start again. Omalluq: Pictures from my Life is on view until March 2025.

jen.zoratti@winnipegfreepress.com

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.