A complicated campaign After 140 years, volunteers of 90th Winnipeg Battalion of Rifles largely forgotten

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

The eight Books of Remembrance, housed in the Peace Tower of the Canadian Parliament Buildings, list the names of the 120,000 dead from the War of 1812, the Nile Expedition and the South African War, First World War, Second World War, Korean War, Newfoundland, Merchant Navy and in the Service of Canada.

There is no book for those who died in the North West Canada Campaign of 1885.

Before putting your Remembrance Day poppy away for another year, perhaps give a thought for the dead of the 90th Winnipeg Battalion of Rifles. Of the nearly 2,000 men who died in the battlefields between 1885-1945 while serving in the Royal Winnipeg Rifles and its predecessors, only seven are interred in Winnipeg, with one each in the Ontario cities of St. Catharines and St. Thomas.

In March 1885, the men of the 90th Winnipeg Battalion of Rifles went to Saskatchewan, as part of the North West Field Force mobilized for the North West Canada Campaign on the South Saskatchewan River.

Departing on March 25, the 90th Battalion travelled 1,200 kilometres by foot, 525 km by rail, and 1,600 km by river and lake boat in 115 days. Its strength leaving Winnipeg was 316 and returning was 232. Nine had been killed and 45 others wounded.

When the battalion’s dead were brought home in June 1885, Winnipeg was black in mourning; when the remaining volunteers returned home in July they were cast as glorious triumphant heroes.

However, history is complex and mutable. So, after 140 years, the volunteers are forgotten and the conventional historical narrative transformed.

In his memoir of the 90th in Saskatchewan, an old soldier named Henry Wilkes tells us that his is “only a story, not the history, of those days.” The personal stories of these veterans are worth recalling. Hopefully, in reading them, the sorrow, spirit, sacrifice and determination of these men of 1885 might be acknowledged.

Who were the men who fought and died in Saskatchewan? All the battalion’s officers were recent immigrants from Britain or Ontario who had adopted Winnipeg as their home. Many of the enlisted men were also recent arrivals. However, several were Manitoba Scottish or French Métis and one was a recent Icelandic immigrant.

They were almost all very young. Four of the nine killed in battle were in their teens, three were barely in their 20s, one was in his 30s and the one officer killed was 34.

The 90th’s Sgt. Edward Campbell spoke positively about the city boys who made up the battalion’s complement, observing that they “are generally well educated and able to look at a question as well, sometimes, as the government who ordered us to arms.” Indeed, when reading their biographies, many became successful businessmen, professionals, local politicians and senior officers in the First World War.

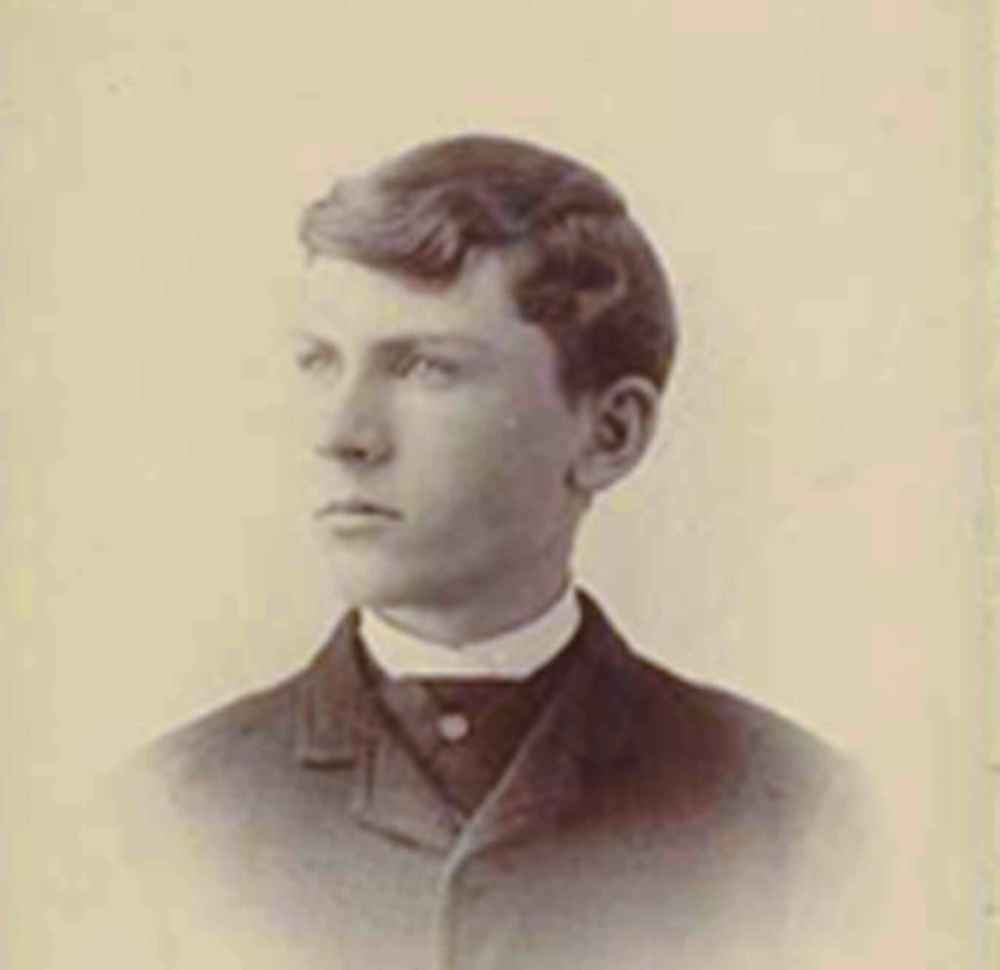

RWR Museum Sgt. Edward Campbell

Campbell also recognized a problem the men faced. Not all wars are justified or popular, as people who read newspapers, even today, know, and Manitoba’s major newspapers blamed the troubles in the North-West Territories on Sir John A. Macdonald’s government.

Amongst the troops, one newspaper wrote, “The feeling that the Métis have been wronged, that the government has been criminally negligent in its treatment of their claims and that the politician should be held accountable for the whole trouble grows more deeply rooted and more widely spread. Feelings nearly akin to sympathy find lodgment in many of the bravest breasts.”

Being an astute man, Campbell puts a fine point on the volunteers’ dilemma: “I think, we sympathize with the rebels but, of course, our duty as soldiers is to obey orders and not to discuss the rights of the question, but I think you will agree with me that is also best to have the right on our side.”

Why would they volunteer? Many, as part of Canada’s Confederation Generation, possessed a keen sense of loyalty and patriotic duty to their new country and the British Empire. Or, it may have been the impulsiveness of youth, as Pte. Wilkes wrote:

“On the evening of March 25th the bugles of the 90th sounded an alarm and boy — like I had to find out what for. I found that the men were to go out in the morning for the Saskatchewan and the Indians were up in arms. Having had a diet of Beetles Dime Library and the heroes of that set of books with details of Buffalo Bill, Custer at the Little Big Horn and Calamity Jane, in mind, I was of course wild to be in this scrap too.”

The new soldiers had to be equipped and the commanding officer, Gen. Frederick Middleton, “was very much dissatisfied with their accoutrements.” Given the sorry state of the Canadian militia finances, their weapons were antiquated, the issued coats, pants and boots shoddy, and, according to many, “very old and rotten and will not stand the campaign.”

This proved to be true, for when the men returned to Winnipeg in July their uniforms were in rags. Many a soldier recalled repurposing flour sacks to repair their pants.

Yet, these problems could be resolved, Campbell said optimistically: “Knowing the spirit of the men of the 90th, I feel confident that they will do credit to Canada and to the city of their adoption.” By March 27, 1885, the men were in Troy (Qu’Appelle), Sask., and, arguably, unprepared for war against a skilled, determined adversary.

Medical student Alex Fergusson, 19, wrote several letters to his mother, which were excerpted in the Winnipeg Daily Sun. He told his parents of his experiences, good, bad and exciting, during the first few days soldiering in Saskatchewan. In part, he wrote:

Had a good time on the train, every man taking his turn at singing or reciting…

The washing is the worst part of the business. You watch your chance and get a horse pail full of water, so alkaline that it is black and the scum taken off it, when boiled is something terrible. You then strip and half a dozen dive into this at once. This is out in the back and below zero, remember….

About 8:30 an officer appointed me orderly of the day. I had to go down to the kitchen, which is every bit as bad as a pig pen, and carry pails of tea and Irish stew and boxes of hardtack and bread. I first served the pickets and guards and the guardroom…

Six of us went to a prayer meeting in the little church way back. After church we came back to the barracks where we now are writing, sleeping, talking, singing, playing cards etc.…

I went on duty as guard on the ammunition car. I could see 3 Indian heads just peeping over the crest of a hill a little piece off. After a while they retreated and I could see them going back through the woods.

On April 2, they marched nearly 30 kilometres to Fort Qu’Appelle. Robert Campbell, a 17-year-old bugler, described the Qu’Appelle Valley as “the most lovely spot I ever saw. I’m sure there is nothing in Scotland to beat it. The grass is beginning to grow. I went around all day without anything on my hands and my coat unbuttoned. I am as burnt as can be. They say in a little while I will do for an Indian.’’

However, spring weather changes quickly and dramatically on the Prairies. “There was a lot of melting snow and the streets were running with water,” William D’Arcy recalled when they left Winnipeg. “It looked as though winter was over but a few days later we were trying to keep warm in below-zero weather.”

After a hard day’s marching, the ravenous soldiers looked forward to a substantial meal. However, army rations were unappetizing and scanty.

“On through sloughs and across creeks,” wrote Wilkes, “in the full of the spring thaw, breaking through the ice in the first part of the day and pulling the guns and stuck transport wagons out of the mud holes later in the afternoon.”

According to Pte. Irvine Snider, “Wood was scarce over most of the trail and the men would huddle around their smoky fires until lights out was sounded, vainly trying to dry boots and socks that had been soaked in marching over trails or submerged in melted snow.”

After a hard day’s marching, the ravenous soldiers looked forward to a substantial meal. However, army rations were unappetizing and scanty. “They made tea from alkaline water. Hardtack of the hardest kind tested the quality of the grinders the Lord had furnished those Canadian boys, well pork imported from Chicago gave their stomachs cause for rebellion, as an alternative corned beef was served,” Snider wrote.

This vitamin-poor diet led to an outbreak of scurvy, which was treated by drinking a horrible-tasting lemon juice concoction.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS A memorial cenotaph at St John’s Anglican Church commemorates the nine members of the Winnipeg Rifles who died in the North West Canda Campaign.

On April 17, Middleton’s force crossed the South Saskatchewan River and prepared to march to the Métis stronghold at Batoche. They rested until April 23 and, fatefully, this was the day the orderly sergeant gave the men their last will and testament forms. They began their march towards the Métis capital the next day.

The 90th fought in the April 24 Battle of Fish Creek and the May 9-12 siege of Batoche. In both battles, the 90th took nearly 50 per cent of the North West Field Force’s casualties. Even though Fish Creek is barely mentioned in standard histories, it is more important in the regiment’s history than Batoche. The battle was the untested riflemen’s “baptism of fire” and where they earned the nickname “The Little Black Devils.”

The Métis, led by Gabriel Dumont, their legendary leader of the annual buffalo hunts and military commander, had planned an ambush and only good luck prevented catastrophe for the men of the 90th. “They were well trained in the art of strategy, practised by those who rely on surprise as a great help in securing a living by trap and gun,” Snider wrote of the Métis plan of attack.

Capt. Charles Witla, a Winnipeg lawyer, described the beginning of the fight. “It was like a flash as we did not at the time expect it. We were all marching at ease and the boys were whistling to keep the step when we heard the sharp ring of the rifle a few 100 yards ahead where the scouts were. All were at work in a few minutes, and the bullets showered over the field like hail in a storm.”

Wagon driver Thomas Bull described the ambush, carnage and anguish at Fish Creek. “We had a horrible fight yesterday. There were seven dead and about 42 wounded and the fire of the enemy was terrific.” The number of wounded were “piled like cord wood on a hay rack to be taken for medical treatment,” recalled Pte. Albert Fisher.

George Flinn, the Winnipeg Daily Sun correspondent embedded with the 90th, wrote that he could not estimate the number of volunteers that were killed or wounded as the battle still raged, but he knew, “many Winnipeg homes were made sorrowful today.”

RWR Museum 90th Battalion Flag circa 1885

As soon as possible, the wounded were moved to Saskatoon and cared for in an improvised hospital. Nurse Phoebe (Parsons) Howard of Winnipeg recalled that they cared for up to 100 casualties and tended the sick and wounded, “friends and foes alike.”

Six Winnipeg Rifles were killed or died of wounds received at Fish Creek and 16 more were wounded. John Code was a 19-year-old law student. William Ennis, also 19, worked for the Winnipeg Street Car Company. Fergusson was 19. George Wheeler, age 17, was a draughtsman in his father’s architectural firm. Lt. Charles Swinford, age 34, was a bookkeeper for a real estate firm.

James Hutchinson, age 38, was working for the Canadian Pacific Railroad in Winnipeg and was the only married man killed during the battalion’s battles at Fish Creek and Batoche.

The first killed was Fergusson, the eldest son of Dr. Robert Fergusson, a professor at the University of Manitoba Medical School. He was a medical student and was expected to stay with the doctors caring for the wounded. However, he rushed to the front at the first opportunity.

A number of Fergusson’s friends’ accounts of his death were published in Winnipeg newspapers. “A brighter or braver boy never lived than he,” Andrew McNally wrote.

Fergusson was lying close to Capt. Christopher Forrest when shot and, just as the bullet struck, he turned over on his elbow and, looking up into the captain’s face, said, “My God Captain I am shot.”

The next fatality on this spot was John Hutchinson. He was sitting down and eating a piece of hardtack taken from his haversack. He had just made some joking remark when a ball struck him in the corner of the left eye and he fell back dead.

The Canadian government broke with the British tradition of burying soldiers in the battlefield where they had fallen.

Charles Swinford was shot on the right side of his head and the bullet shattered his skull, lodging in his brain. “For a long time,” wrote George Flinn, “he would not believe he was seriously injured and as he was led to the rear persisted that it was only a slight wound but his skull was shattered, poor fellow, and the brain was actually exposed.”

Middleton stayed close to the front lines all day to inspire his men. “I couldn’t do otherwise. I had green troops and still worse green officers — green in the sense that they had never been under fire before. They did well and bravely,” the general stated.

The troops remained in camp at Fish Creek until May 8, then were ordered to advance on Batoche. Middleton did not want to risk another Fish Creek, so to conserve his soldiers’ lives, he planned a slow methodical encirclement. His plan was not perfect, but on May 12, Batoche was captured and the Métis leadership soon taken into custody.

Three more men of the 90th were killed and 10 others wounded. The men killed were Pte. James Frazer, 23,who ran a grocery store on Jemima Street in Winnipeg; Scottish-Métis Pte. Richard Hardisty, 21, who came to Winnipeg in 1878; and Pte. Alexander Watson, 27, who moved to Winnipeg in 1881 and was engaged to be married. He was interred in his home town of St. Catharines, Ont., and, in 1886, the Watson Monument was erected there.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS The North West Rebellion memorial cenotaph at St John’s Anglican Church

The Canadian government broke with the British tradition of burying soldiers in the battlefield where they had fallen. If buried, the bodies were exhumed, embalmed and sent to their home towns for a military funeral and commemoration. “The saddest phase in connection with the rebellion is the contemplation of the gloom it brings to households,” the Winnipeg Daily Sun wrote.

The first funerals were for Fergusson and Swinford on May 6 in Winnipeg. Businesses, government offices and schools were closed; flags were flown at half-mast and people lined city streets as the funeral procession made its way down Main Street to St. John’s Cathedral graveyard.

The Manitoba Free Press wrote that the May 24 funerals of Code, Hardisty and James Frazer “will long remain the most prominent event in the history of the city.”

Upon their arrival in Selkirk, excited citizens treated them to lunch, which, of course, was a great relief from the hardtack and beans they had been eating for nearly four months.

The funerals for Wheeler and Ennis were held on July 6. After the service and procession to the graveyard, the paper reported that “the caskets were lowered into the grave alongside their fallen comrades in arms. At the conclusion of the service the firing party fired the customary three volleys and it was all over.”

The 90th did not return to Winnipeg immediately after the Battle at Batoche, much to the dismay of the officers and men. In early July, river steamers transported the troops down the North Saskatchewan River to Lake Winnipeg. There, the men were transferred to barges that took them to Selkirk where they boarded a train bound for Winnipeg.

Upon their arrival in Selkirk, excited citizens treated them to lunch, which, of course, was a great relief from the hardtack and beans they had been eating for nearly four months. What made the men particularly happy were the kegs of beer on the tables.

The July 15 editorial of the Manitoba Daily Free Press praised the soldiers’ sacrifices: “With particular warmth we grasp the Ninetieth by the hand and say ‘Well done gallant boys.’ You have doubly endeared yourselves to us; we shall not soon forget your sacrifices; welcome, welcome home.”

However, it didn’t want its readers to forget who caused the rebellion:

“For all this misery, for all this degradation, the government is responsible. They first goaded the Métis into revolt through the agency of their crass and incomprehensible policy and their dishonest and incapable officials and then sent against them an army of brave men it is true (for were they not Canadian volunteers) but also a host of sharks of the kind in which their souls, especially delight.”

Winnipeg planned an over-the-top homecoming. A victory arch was built near city hall and flags, banners and decorations adorned streets and office buildings. The men marched past the cheering crowds in their tattered, dirty uniforms, through the arch and assembled at city hall. There they were officially greeted by the lieutenant-governor, premier and mayor, who praised the volunteer soldiers for doing their patriotic duty and for their bravery.

The men were soon released to celebrate their return. They were pleased to hear the mayor had declared the taverns would remain open all night and police were instructed not to interfere with the festivities.

Mayor Henry Shaver Wesbrook announced in his speech that Winnipeg would never forget their loyalty and bravery, with a volunteer memorial committee soon struck.

The first choice for the monument’s site was at Portage and Main; however, the ground was found to be structurally unsuitable, so a site in front of the new city hall was selected.

WINNIPEG FREE PRESS ARCHIVES The unveiling of the Volunteer Monument outside city hall on Sept. 28, 1886, drew a sizeable crowd. The monument is now situated just off Main Street between the Manitoba Museum and Centennial Concert Hall.

The Volunteers’ Monument bearing the names of John Code, William Ennis, Alexander Fergusson, James Frazer, Richard Hardisty, John Hutchinson, Charles Swinford, Alexander Watson and George Wheeler was dedicated in front of city hall on Sept. 28, 1886.

The 90th Battalion erected its own monument by the graves of the men interred in the St. John’s Cathedral cemetery, which also served to remember their companions resting in St. Catharines and St. Thomas.

Every year at the St. John’s Anglican Cathedral’s Remembrance Day service, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles hold a brief ceremony to honour the memory of the Rifleman who lost their lives during the North West Canada campaign. Sentinels, in period uniform, are posted at the monument, a bugler sounds the Last Post and, after two minutes of silence, the bugler sounds the rouse and, historically, three volleys are fired — then it is all over.

Ian Stewart is author of Pork, Beans & Hard Tack: Stories From Winnipeg’s 90th Rifles.