Legendary former WAG director Eckhardt accused of Nazi past

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/11/2023 (746 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A prominent art historian and driving force behind the creation of the modern-day WAG-Qaumajuq has been accused of a Nazi past.

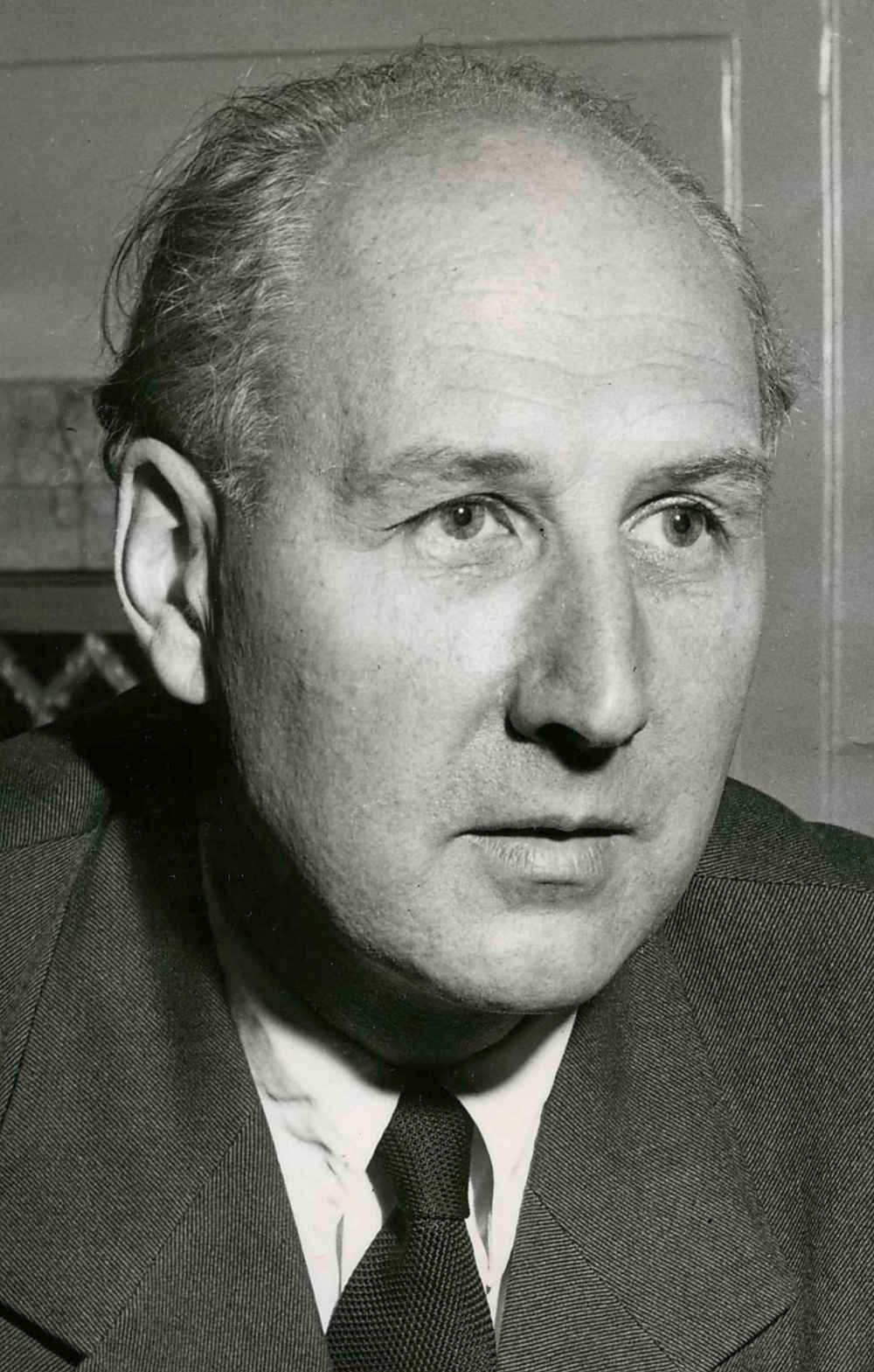

A Canadian magazine article published Thursday details the life of Vienna-born Ferdinand Eckhardt, who directed the Winnipeg Art Gallery from 1953 to 1974 and became one of the most high-profile Manitobans of the 20th century.

The Walrus article, titled “Was the Winnipeg Art Gallery led by a Nazi?” by Winnipeg writer Conrad Sweatman, says Eckhardt, who moved to Berlin in the late 1920s, signed an oath of allegiance to Nazi leader Adolf Hitler in the 1930s.

Eckhardt further wrote about artistic goals for Germany in journals that supported the Nazi regime, which ruled the country from 1933-45, launched the Second World War in 1939, and was responsible for the Holocaust.

“The only surprising thing is so many things are missing and not substantiated or provided without citations or references, so there are a lot of big gaps,” Stephen Borys, director and chief executive officer of WAG-Qaumajuq, said Thursday of the magazine article.

The Walrus cites a 1973 public lecture Eckhardt attended at the Winnipeg gallery delivered by Karl Stumpp, a German ethnographer accused of participating in the murder of Jews in 1941 in what is now Ukraine but never brought to trial.

“Literally by (Eckhardt) being conscripted into the army and writing that one article, which he couldn’t get published anywhere else and then he got a lot of attention for it, it is strange to then tie him in with a lecture at the WAG in 1973,” Borys said.

The Holocaust-Era Provenance Research and Best Practice Guidelines Project — launched by the Canadian Art Museum Directors Organization and the federal Canadian Heritage department — previously investigated WAG-Qaumajuq’s collection (along with other galleries in Canada), including works Eckhardt and his wife Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté had donated, and found no ties to Nazi looting of Jewish families before or during the war, Borys said.

“Where there’s gaps in provenance between 1936 and 1945, if we don’t know where the painting was or changed hands, it becomes a candidate for further research,” he said. “There are no gaps in the provenance of the works that he acquired, that she acquired and that eventually made their way to the WAG.”

The Walrus article is based heavily upon Eckhardt’s unpublished memoirs, which the Archives of Manitoba had held since his death in 1995, and made accessible to the public this fall.

Eckhardt (1902-95) joined Bayer (maker of Aspirin) as an advertising manager in 1933. It was a subsidiary of chemical conglomerate IG Farben in the 1930s; the Walrus says Eckhardt later transferred to Bayer’s “scientific division.”

One of IG Farben’s many businesses supplied Zyklon B, the poison gas used at concentration camp gas chambers such as Auschwitz. An estimated six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust.

Ruth Bonneville / Winnipeg Free Press files Eckhardt was a driving force behind the creation of the modern-day WAG-Qaumajuq.

Eckhardt was conscripted into the German army from 1942-44, and returned to work at Bayer until the end of the war.

Eckhardt and his Moscow-born wife, Eckhardt-Gramatté, a composer, violinist, pianist and teacher, were married in 1934. They moved to Vienna after the war, where Eckhardt worked at Austria’s national art museum.

The magazine article suggests Eckhardt’s Nazi past led him to leave in 1953, and move to Winnipeg, where the WAG hired him as director.

Eckhardt and Eckhardt-Gramatté (1899-1974) became city leaders, with Eckhardt spearheading the movement for the construction of a new home for the gallery, which eventually opened at its present location on Memorial Boulevard in 1971.

It includes Eckhardt Hall, a 3,000-square-foot event space, where exhibition openings are celebrated.

The Winnipeg gallery was renamed WAG-Qaumajuq, after the 2021 opening of the museum devoted to the display and storage of the world’s largest collection of Inuit art.

It was Eckhardt who acquired the gallery’s first work of Inuit art: a stone-and-ivory carving by Pinnie (Benjamin) Naktialuk, titled Mother Sewing Kamik, which was on sale at the nearby downtown Hudson’s Bay store in 1957.

Eckhardt-Gramatté’s musical career flourished in Manitoba. She published 10 classical compositions from 1953 until her death in Stuttgart, Germany, including her symphony No. 2 (Manitoba) in 1970 — the year she received an honorary doctorate from Brandon University.

Eckhardt received the same honour in 1990.

BU named its conservatory of music after Eckhardt-Gramatté. In 1976, it began hosting the Eckhardt-Gramatté National Music Competition every two years.

“This is concerning information to learn about Eckhardt’s background and it will start some difficult conversations here,” BU spokesman Grant Hamilton wrote in an email Thursday.

The University of Manitoba named its music library after Eckhardt-Gramatté. The Winnipeg-based school granted Eckhardt an honorary degree in 1971.

“These allegations are alarming and disturbing and, if accurate, would put the naming of the music library in violation of UM’s naming policy,” a spokesperson wrote in an email. “(U of M) is conducting a full review into the naming of the space to determine next steps.”

The University of Winnipeg, which also has connections to Eckhardt-Gramatté, said it will review the allegations to determine if any action is necessary.

“Although no campus facilities or programs are named after Ferdinand Eckhardt, a lecture hall and a library collection are named after his wife,” U of W spokesman Caleb Zimmerman wrote in an email.

“We take the content of the article very seriously and are committed to thoroughly examining the matter and acting according to our institutional values of human dignity, equality, respect and diversity.”

In recent years, the Manitoba Museum has received a large collection of personal belongings of Eckhardt, Eckhardt-Gramatté and German painter Walter Gramatté (Eckhardt-Gramatté’s first husband), said curator of history Roland Sawatzky.

Most of the items belonged to Eckhardt-Gramatté and Gramatté, who was 32 when he died of an illness in 1929. Sawatzky believes some of Eckhardt’s belongings date to his time with Bayer.

“But besides that, which I recognized as suspect in terms of Bayer’s role in the Third Reich, I have not come across anything that would indicate a Nazi connection,” he wrote in an email. “I was looking out for it.”

Sawatzky doesn’t believe the Winnipeg museum is in possession of any valuable pieces that may have been looted by Nazis.

“No gold or silver items or anything along those lines,” he wrote. “It’s all pretty humble, personal stuff, as far as I can remember, and much of it collected before Walter’s death.”

Sweatman said he was inspired to look into Eckhardt’s past after watching the 2001 HBO film Conspiracy, which dramatizes the 1942 Wannsee Conference, where Nazi leaders such as Adolf Eichmann and Reinhard Heydrich made plans for the so-called “Final Solution.”

The film mentions one of the Nazis at the conference — not Eckhardt — had made his way into North America’s arts and cultural industries.

Sweatman said he admires the WAG-Qaumajuq’s commitment to artistic excellence and social justice, and believes the revelations about Eckhardt’s past will force it to act.

“I know is an outstanding, conscientious institution and I believe they’ll move forward in a spirit of good faith on this.”

alan.small@freepress.mb.ca

chris.kitching@freepress.mb.ca

Alan Small

Reporter

Alan Small was a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the last being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

As a general assignment reporter, Chris covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, November 10, 2023 9:14 AM CST: Changes to conservatory from school

Updated on Friday, November 10, 2023 12:15 PM CST: Minor copy edit

Updated on Sunday, November 12, 2023 2:26 PM CST: Minor copy edit