Left out, sold out Rupert’s Land inhabitants — mainly First Nations and Métis communities — were completely blindsided by the Dominion of Canada’s purchase of their homeland from the Hudson’s Bay Co. in 1869

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/10/2024 (398 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Excerpt from Treaties, Lies and Promises: How the Métis and First Nations Shaped Canada by Tom Brodbeck. Reprinted with permission of Ronsdale Press.

When the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) reached an agreement to sell Rupert’s Land to Canada in the spring of 1869, it came as a complete surprise to the people living in what is today Western Canada. They were neither consulted on the proposed annexation nor given any details about how it would affect their lives.

Under the agreement, negotiated in London, England, between the British government, HBC and Canada, Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory would be purchased by the new Dominion of Canada for £300,000 ($1.5 million in Canadian dollars at the time). HBC would retain a small portion of the land and Canada would establish a territorial government in the region, headed by a lieutenant-governor.

The inhabitants of Rupert’s Land, including an estimated 12,000 people living in the Red River Settlement — mostly French- and English-speaking Métis in what is today the core area of Winnipeg — were left entirely in the dark. There were no official visits from representatives of the Canadian government, no town hall meetings hosted by federal or British authorities, and no proclamations spelling out how existing landholdings would be treated.

From the perspective of First Nations communities living in Rupert’s Land, their territory was sold without their consent. Anishinaabe, Cree and other Indigenous groups were given no information about when, or whether, treaties would be negotiated to protect their territorial and hunting rights. They learned of the proposed sale of their homeland through secondary sources.

The people most affected by the largest territorial transaction in Canadian history were barely an afterthought. They played no role in the negotiations held in London and had no input into how Canada planned to assume control of the territory.

When word of the agreement reached Red River in the summer of 1869, the French Métis — led by a young and fiery Louis Riel — mobilized. They organized meetings and held emergency planning sessions throughout the settlement. Within weeks they formed an armed militia to prevent what they saw as an invasion of their homeland by a foreign entity.

When a party of land surveyors from Canada arrived unannounced that summer — well before the deed of surrender with the HBC was finalized — Métis leaders drove them away.

The Rupert’s Land purchase was Canada’s first step towards opening the West for colonial settlement. It was scheduled to take effect on Dec. 1, 1869. William McDougall was chosen by Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, to be the first lieutenant-governor of Rupert’s Land and the adjacent North-Western Territory.

McDougall travelled by train from Ottawa to Minnesota through the United States in the fall of 1869. Travelling through the United States by rail was the usual route to Red River from Eastern Canada at that time. The alternative was a gruelling, weeks-long journey through the rivers, lakes and dense forests of Ontario that spanned more than 1,000 kilometres. There was no railroad or telegraph directly connecting Red River to the outside world in 1869.

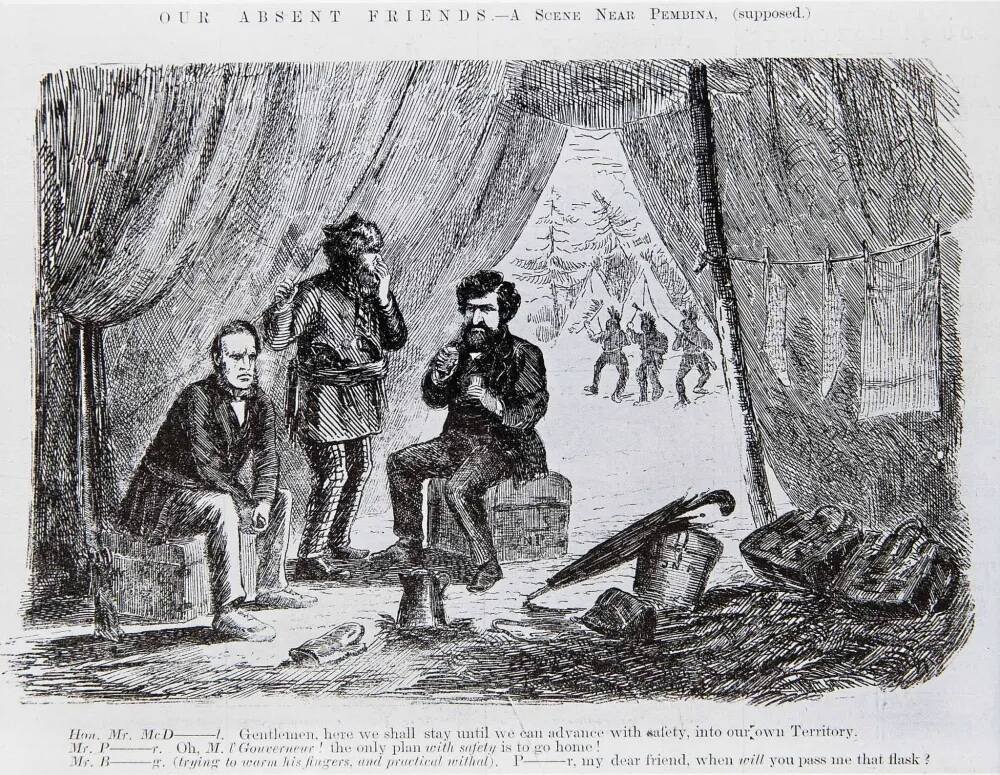

A political cartoon from 1870 depicts William McDougall’s entourage being stalled at Pembina. (Archives of Manitoba)

McDougall and an entourage of 20 people, including family members, government officials and support staff, travelled north by ox cart from St. Cloud, Minn., where the railroad ended in those days. The would-be lieutenant-governor had one of the finest homes in the Red River Settlement picked out for him in the parish of St. James, about 10 kilometres west of Upper Fort Garry. It was said to be the most suitable dwelling in the territory for a lieutenant-governor.

But McDougall would never see the inside of the St. James home, nor would he assume his position as the Queen’s representative in the Red River Settlement. The lieutenant-governor designate was refused entry into the territory. He was stopped a few kilometres past the U.S. border by a party of armed French Métis, who objected to the federal government’s unilateral annexation of their homeland. It was a brazen and unexpected response that escalated into a seven-month David-and-Goliath showdown between the small community of Red River and the Dominion of Canada.

Most people in Red River were not opposed to joining Canada, which had formed just two years earlier on July 1, 1867. Many Métis considered themselves British subjects and were loyal to Queen Victoria, regardless of their French, English, Catholic, Protestant or Indigenous backgrounds. Red River settlers — made up mostly of French- and English-speaking Métis — celebrated Queen Victoria’s birthday long before joining Canada.

What many of them objected to was joining Confederation unconditionally. They wanted input into the terms of joining Canada. When McDougall arrived at the border, the people of Red River had no commitment from the federal government that their language, culture, landholdings or way of life would be protected. For some, blocking McDougall at the border and taking up arms was the only way to get Canada’s attention.

Some First Nations leaders were given assurances that treaties would be negotiated if they remained neutral during the Red River Resistance

The federal government’s plan was to govern the region as a territory, with provincial status and an elected government to be established at a later date. Until then, it would be administered by a lieutenant-governor and a federally appointed council. Without provincial status and a democratically elected legislative assembly, there were no assurances local inhabitants would have input into political affairs, at least not during the formative years.

Red River residents were concerned that under the proposed takeover, the community would be overrun by settlers from Eastern Canada, who would acquire land and disrupt the social equilibrium that had developed over generations. Canada was warned repeatedly about the risks of assuming control of the Northwest without consulting the people who lived there.

On Nov. 2, 1869, the French Métis seized Upper Fort Garry, the HBC trading post in the heart of the Red River Settlement. Within weeks, they declared a provisional government and demanded direct negotiations with Canada. Three months later, with the support of English-speaking Métis, the people of Red River created the region’s first elected legislative assembly.

John A. Macdonald, stunned by the unfolding events and taken aback by the Métis community’s resolute defence of their homeland, agreed to negotiate with a small delegation sent from Red River. Canada’s acquiescence, which culminated in the passage of the federal Manitoba Act, was a major victory for the people of Red River, one that shaped the political and cultural future of Manitoba.

First Nations, meanwhile, took no active role in the Red River Resistance. Some First Nations leaders were given assurances that treaties would be negotiated if they remained neutral during the uprising. When Manitoba’s first lieutenant-governor, Adams Archibald, arrived in the new province in September 1870, First Nations chiefs were the first to greet him at the mouth of the Red River. They demanded and secured face-to-face talks with the Crown the following year to negotiate Treaty 1.

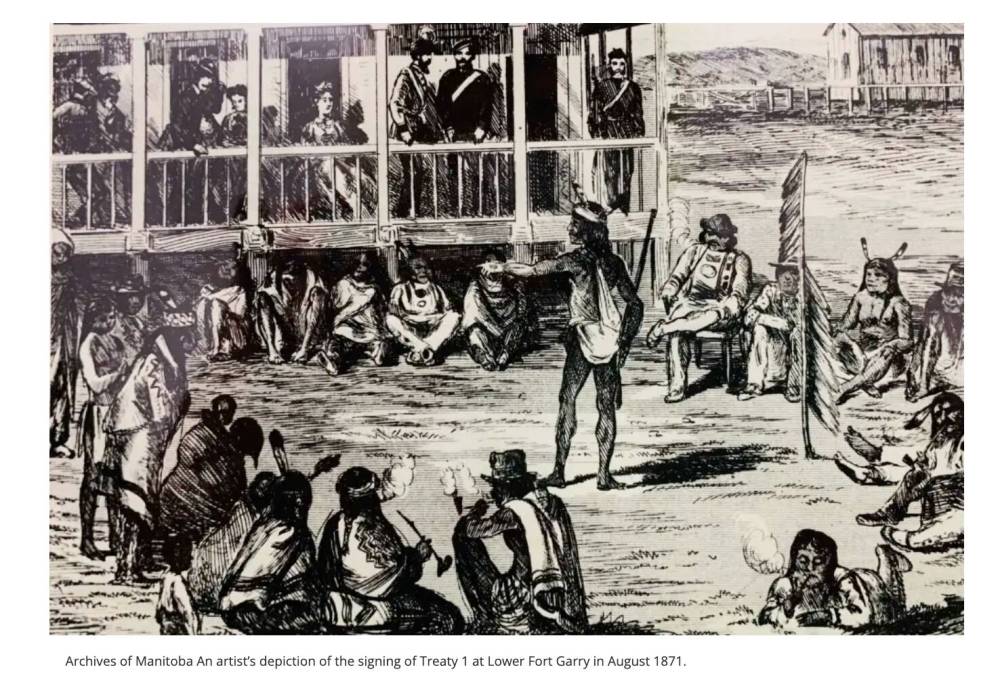

An artist’s depiction shows the signing of Treaty 1 at Lower Fort Garry in August 1871. (Archives of Manitoba)

Treaty 1 negotiations opened in spectacular fashion in July 1871 with performances by Indigenous dancers and drummers at the Stone Fort, a Hudson’s Bay Company post downriver from the village of Winnipeg. About 1,000 Indigenous people gathered for over a week to witness the historic talks.

Chiefs representing seven First Nations bargained through interpreters during seven days of negotiations that were often heated, sometimes humorous and starkly revealing of the colonial mindset and perceived racial superiority of Crown negotiators. Treaty 2 was negotiated several weeks later, covering what are today parts of central Manitoba.

In 1875, government officials travelled throughout Lake Winnipeg by steamboat, the first vessel of its kind on Manitoba’s largest lake, to negotiate Treaty 5 in what is today central and northern Manitoba.

Tom Brodbeck is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist.

Tom Brodbeck is an award-winning author and columnist with over 30 years experience in print media. He joined the Free Press in 2019. Born and raised in Montreal, Tom graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1993 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and commerce. Read more about Tom.

Tom provides commentary and analysis on political and related issues at the municipal, provincial and federal level. His columns are built on research and coverage of local events. The Free Press’s editing team reviews Tom’s columns before they are posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press’s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.