Canadian horror picks with slashed budgets, killer scores

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Canadian films, at least outside Quebec, don’t get enough love.

Lo-fi grit, unrefined performances and other rough edges often take on an endearing quality in Canadian music.

In film, they tend to trigger a deadly label: “amateurish.”

TAKE 5

In a regular series, the Free Press explores FIVE GREAT THINGS

However, there’s at least one movie genre where amateurism, when it happens, feels appealingly punk, and that’s horror.

In the 1980s, cheap slashers, especially — a masked killer slices and dices dumb teenagers — turned the film industry on its head, paving the way for a new generation of indie filmmakers, many of whom went on to more prestigious fare.

Canada was a natural contender to compete in this new low-budget craze, giving us the “Canuxploitation” phenomenon and some of the genre’s most famous entries.

Ironically, despite the genre’s lowbrow trappings, it also created space for a more highbrow medium: classical music. And not just any classical music, but the avant-garde stylings of modernism. Atonal, dissonant experiments inherited from early to mid-20th century Europe found a natural home in horror and could now pierce mainstream North American culture.

Today, the so-called “elevated horror” trend sees younger Canadian filmmakers such as Chris Nash (In A Violent Nature) and composers including Colin Stetson (Hereditary) and Mark Korven (The Witch) make their names in acclaimed movies often attached to the Hollywood arthouse A24 studio.

But there’s a certain plucky charm to Canuxploitation and earlier low-budget fare, which was often not only Canadian through and through, but pioneered the horror genre’s best-worn tropes.

With Halloween just around the corner, we take a look at some of our country’s most fun and notable low-budget horror movies, with special attention to entries featuring striking musical scores.

Black Christmas (1974)

Black Christmas — shot in and around a snow-covered University of Toronto — is one of the first modern slashers.

Members of a surprisingly star-studded cast (including Olivia Hussey, Margot Kidder and Keir Dullea) are stalked by a mysterious killer in a sorority house.

John Carpenter’s 1978 Halloween, which triggered the slasher craze, may be the better picture, but he’s been up-front about working with formulas established by this taut, imperfect film.

There’s the killer POV cinematography; the “final girl” archetype; the masked, motiveless serial killer; the “He’s calling from inside the house!” moment.

Black Christmas laid the groundwork for films like John Carpenter’s Halloween.

In other ways, Black Christmas runs up against contemporary viewers’ expectations.

Virgins tend to survive slashers, rewarded for their purity. Horny, pot-smoking teenagers get a machete to the face.

The film’s final girl not only skirts this cliché, but she opts to get an abortion — an affront to Canada’s restrictive abortion laws at the time, as well as to her overbearing boyfriend.

In a funny twist, Black Christmas makes him — a classical piano student with a taste for discordant European modernist music — the suspected killer. This slasher may not idolize chastity, but it does seem to share middle America’s suspicion of avant-garde types.

Despite mining the base metals that built a key horror subgenre, Black Christmas was mostly dismissed by critics at the time of its release. It’s since become considered a minor Canadian classic, with Quentin Tarantino calling it one of his favourite slashers.

Scanners (1981)

You know the one, with the heads that keep exploding.

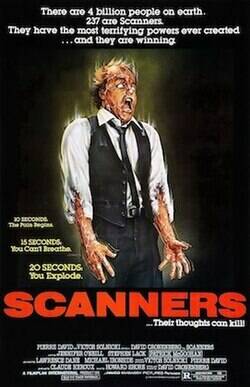

The iconic poster for David Cronenberg’s Scanners.

You know it because of its iconic poster — Michael Ironside’s eyes rolled back as he looks like a balloon about to burst — and perhaps also its bonkers plot about telekinetic weaponry, world domination, rogue psychics and more heads going pop, pop, pop.

But other elements conspired to make David Cronenberg’s first high-grossing film — likewise dismissed by critics at the time but now heralded as a milestone in body horror and Canadian cinema — the campy powerhouse that is.

One of these is Canadian composer Howard Shore’s score, a blend of orchestral and synth sounds that cleverly straddles the line between high-minded atonalism and new age pop: Boulez and Schoenberg meet Philip Glass and Emerson, Lake & Palmer.

Scanners was a breakthrough for both Cronenberg and for Shore — who went on to score The Lord of the Rings, most of Cronenberg’s work, six of Martin Scorsese’s films and dozens more Hollywood features.

The Burning (1981)

The Burning isn’t just inspired by Friday the 13th (1980).

The cheap Canadian-American movie is a shameless ripoff of that hit slasher, itself an inferior cash-grab that spawned a major and majorly crappy franchise.

The Burning is inspired by slasher hit Friday the 13th.

In both, counsellors return to a campsite years after a horrible accident and suddenly find themselves stalked and butchered in a revenge plot that may or may not involve the camp caretaker.

So, it’s surprising to find that The Burning, which holds an 85 per cent Fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes, is actually pretty solid. It features one exquisitely executed, iconic scare — involving an overturned canoe, pruning shears and a patient control of suspense rare for slashers — and a handful of soon-to-be-famous actors, including Holly Hunter and Jason Alexander, flashing their talent in modest roles.

Still, there’s one way in which The Burning is weaker than Friday the 13th.

Next to Harry Manfredini — Friday the 13th’s composer, with his cluster chords, aleatoric writing and slippery glissandi — Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman’s synths bounce along a little too chipperly for horror.

Give it two years, Wakeman, then you can make Owner of a Lonely Heart.

My Bloody Valentine (1981)

Of all the Canuxploitation, shlock connoisseur Quentin Tarantino reserves his highest praise for this one, calling it his favourite slasher.

My Bloody Valentine is more guts, gore and eviscerated hearts than scares — and closer in spirit to the grindhouse that inspired Tarantino’s Death Proof. A masked killer, in this case a miner with a pickaxe, returns to a small mining town for a revenge scheme connected to an accident that happened on Valentine’s Day 20 years earlier. So far, so familiar.

Killers in slashers tend to come in two varieties: motiveless (Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees, etc.) and idiotically motivated, as in MBV. In the second case, the film is basically a vicious instalment of Scooby Doo, where an invulnerable killer wielding a sharp piece of metal suddenly becomes all too easy to foil after being unmasked.

With either variety, small towns and communities are usually the right setting. Their humdrum normalcy — wholesome, but teeming below the surface with generation-old grudges and sexual temptation — makes them ripe for transgression.

My Bloody Valentine’s use of working-class adults, rather than suburban high school students, is novel, and we enjoy the scenic locations of Cape Breton, N.S.

But otherwise it’s pretty stock, with the film’s unsung star being Paul Zaza’s score.

It sounds like something you would hear at the Winnipeg New Music Festival in earlier days: dense, electro-acoustic, brooding when it isn’t assaulting — and really very upsetting. It’s great.

The Clown at Midnight (1999)

A serviceable slasher shot in Winnipeg and produced by Paquin Entertainment, this film takes its inspiration from the glut of teen slashers in the 1990s, inspired largely by Wes Craven’s Scream.

The Clown at Midnight — which managed to attract a few stars, including Christopher Plummer, Margot Kidder and Tatyana Ali — isn’t self-conscious enough for Craven’s style of postmodern wit, but it’s just conscious enough to deliver a few jolts and giggles and keep its pulse longer than most of its hapless characters.

Hapless teens stuck in an opera house (which locals will recognize as the Burton Cummings Theatre) must survive a murderous, low-rent Pagliacci in The Clown at Midnight.

They’re stranded, for one pointless reason or another, in an opera house (very obviously the Burton Cummings Theatre to locals). Who’s stalking them? A low-rent Pagliacci, armed with a grin and a clownishly complex arsenal.

What makes him tick? Could it be, as with the original Pagliacci, the inability to separate theatre from life? The bitter irony of having to make others laugh while dying inside?

It doesn’t matter in the end. Leoncavallo’s musical and dramatic themes weave in and out only as a sort of meme. Score-wise, it’s Winnipeg’s Glenn Buhr — who had finished up a few years before as the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra’s composer-in-residence, where he co-founded the New Music Festival with conductor Bramwell Tovey — who does most of the heavy lifting, and that’s actually a good thing.

Buhr would come to distinguish himself as among the more tuneful and tonal of his generation of Canadian composers, but here he leans into trembling cluster chords — that Bernard Herrmann and Krzysztof Penderecki style we associate with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho — to their full horror-camp potential.

conrad.sweatman@freepress.mb.ca

Conrad Sweatman is an arts reporter and feature writer. Before joining the Free Press full-time in 2024, he worked in the U.K. and Canadian cultural sectors, freelanced for outlets including The Walrus, VICE and Prairie Fire. Read more about Conrad.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.