Staycation with a twist Founded by a Manitoban in southern Missouri, the world’s only other Winnipeg peaked at a population of several dozen and had disappeared from maps by the 1980s

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/07/2023 (830 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There are no roadside billboards welcoming visitors to Winnipeg; no overhead banners billing it as one great city or detailing what it’s made from. Heck, there isn’t even a playful poke à la an old episode of The Simpsons, when Bart and the gang are greeted by a panel reading “Now entering Winnipeg: we were born here, what’s your excuse?”

Instead, the only clue to indicate we’d reached our destination after close to 18 hours behind the wheel was a street sign spelling out “Winnipeg Drive.” Thankfully, we’d been told to keep watch for the green-and-white marker, which sits atop a stop sign where said drive meets Route 32, a two-lane highway that stretches 459 kilometres from El Dorado Springs to the west, to Ste. Genevieve to the east, passing through places such as Bolivar, Lebanon and Farmington along the way.

A stop sign at Route 32.No worries if those locales don’t ring a bell; the thing is, Toto, we weren’t in Manitoba, anymore, but rather, southern Missouri, home of the only other Winnipeg on the planet.

Situated in picturesque Laclede County, approximately 100 kilometres southeast of Lake of the Ozarks, where the popular Netflix series Ozark is set, our U.S. counterpart boasts a population of precisely zero. That is, unless you count the three dozen or so souls occupying the perfectly manicured cemetery adjacent to the Winnipeg Christian Church, where, as scheduled, we are joined by sisters Renee Taylor and Stephanie Stiller.

For as long as each can remember, Taylor and Stiller, who live in Springfield, Mo., and Jefferson City, Mo., respectively, have hooked up at the church and cemetery ahead of the American Memorial Day long weekend to tend to some of their ancestors’ gravesites. Their maternal grandparents, Arthur and Flora Lamkins, both of whom are buried there, dually ran Winnipeg’s post office and general store in the 1940s and ’50s, back when Winnipeg was a thriving, albeit tiny, community.

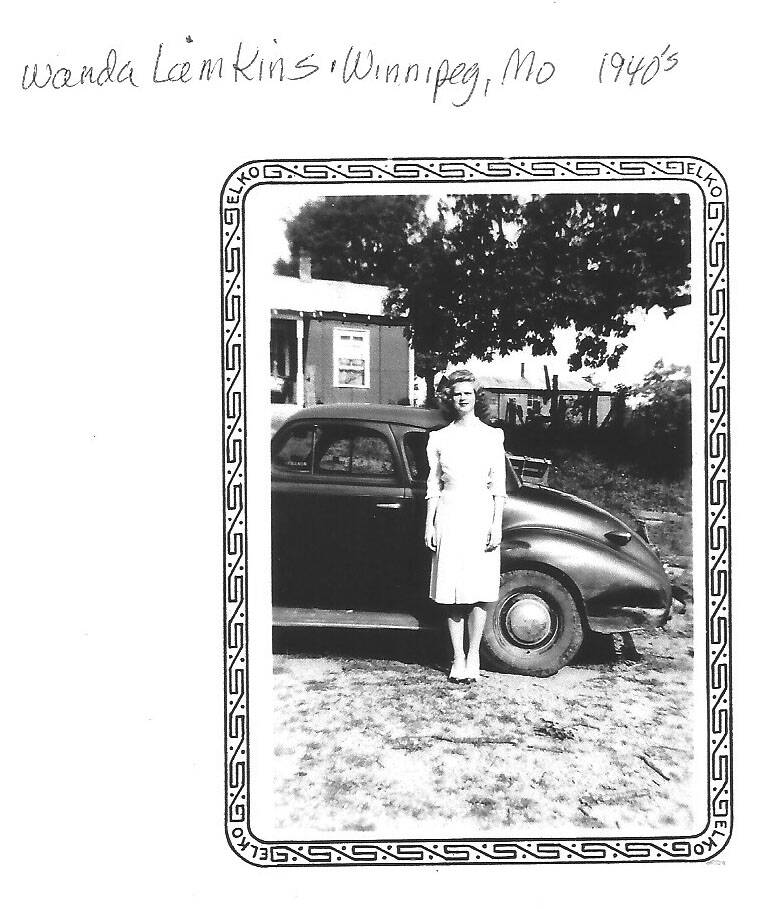

Furthermore, their mother Wanda Weaver (nee Lamkins) was born and raised in Winnipeg, Mo., as was her sister Goldia and four brothers Clyde, Victor, Vernon and Dennis. (Dennis, the youngest of the six, died at age 89 five days before our arrival, an unfortunate set of circumstances as he would have “talked your ear off about growing up in these parts,” Taylor says.)

David Sanderson photo Sisters Renee Taylor (left) and Stephanie Stiller tend to gravesites at Winnipeg Cemetery.

Although their mother never travelled to “the other Winnipeg,” she was fascinated by it and the province of Manitoba in general, her daughters say in unison. She had a longtime penpal who lived in St. Vital. The two were in touch regularly before Weaver’s death.

“Mom passed in 2019, but oh my goodness, if she’d known you’d driven here all the way from Canada, she’d have been tickled pink,” Stiller says, reaching for a broom and rake she brought along to assist with their groundskeeping.

“Now to be clear,” she continues, pausing to wipe her brow on a cloudless day when the temperature is expected to climb to 30 C, “is your story going to be about a trip to the States in general, or just Winnipeg?”

Just Winnipeg, we assure her, referring to it as a staycation piece… with a twist.

(Note: If you ever want to spark a reaction from a border official in Pembina, N.D., tell them that you live in Winnipeg, and that you’re headed to Winnipeg, for travel purposes.)

According to an article titled We’ll show you Winnipeg, Missouri that ran in the Winnipeg Tribune Sept. 17, 1938, Winnipeg, Mo., was founded in 1906 by William C. Gibson.

Ken Kimbel, the author of the story, reported that Gibson was from Winnipeg, Man., originally, and that he made his way south in the early 1900s looking for employment. The area where he settled, just south of the Gasconade River, was 10 kilometres from the nearest existing post office. Because that was a fair distance, given the primary mode of transportation was horse-and-buggy, he established a post office close to where he and a few other families were living “two miles from the Pulaski County line.”

The outlet needed a name, of course. He dubbed it Winnipeg in honour of his hometown.

Gibson returned to Canada from Missouri in 1910 but the tag stuck. In Kimbel’s article, the then-postmaster, Ted Loney, was quoted as saying “there are five families living here in Winnipeg, making a total population of 26 people.”

Wanda Lamkins Weaver in the 1940s.“People of Winnipeg sure enjoy themselves, in summer especially, when they go fishing, swimming or boat riding,” Loney said. “Last year there were some folks here from Winnipeg, Canada. We play(ed) croquet and baseball… Winnipeg having her own team.”

Wanda Weaver, Taylor and Stiller’s mother, picks up the story from there, thanks to a typed 50-page essay called “History of Winnipeg, Missouri, by Wanda (Lamkins) Weaver,” which she put the finishing touches to in March 1995.

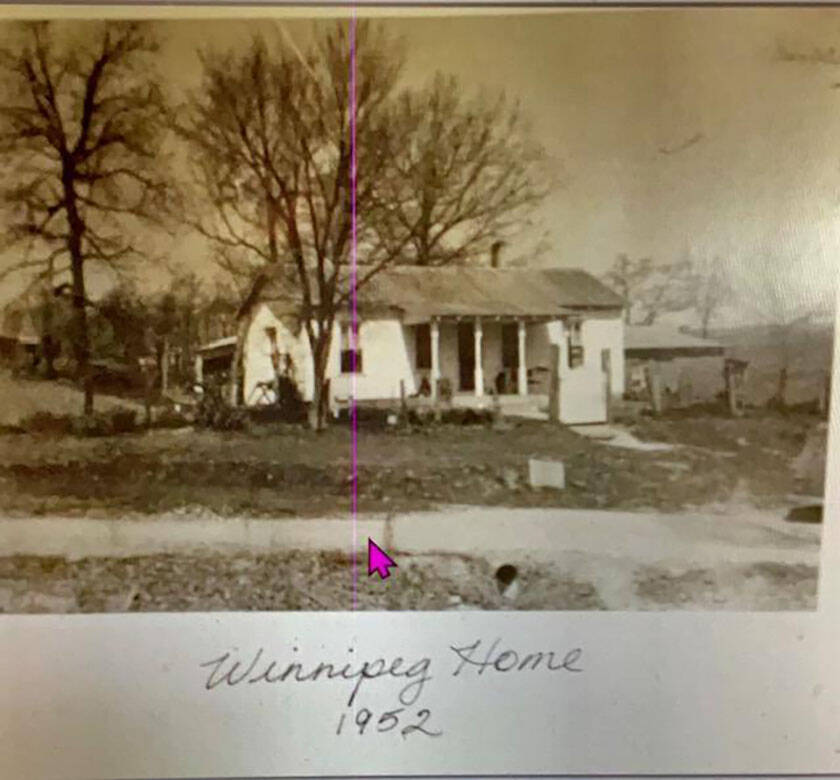

Weaver, who was born in 1925, wrote that by the late 1930s, the church and post office had been joined by a sawmill and flour mill, along with her parents’ general store.

“Area residents brought eggs, cream and chickens to the store to sell. Rope and binder twine was also sold, also nails and some hardware items, cattle feed and dry goods, soda and candy,” she wrote. She added that “candy bars don’t taste as good today as they did then,” referencing Snickers, Baby Ruth and Butterfinger bars as her personal favourites.

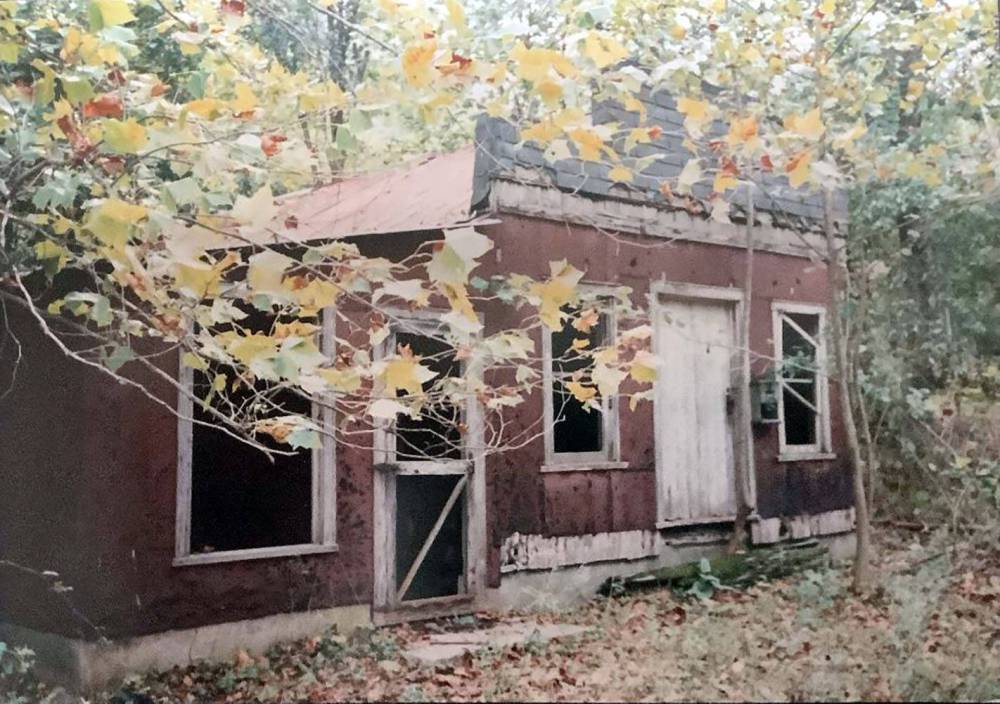

David Sanderson photo Little remains of the Winnipeg, Mo., general store, which was situated off Winnipeg Drive.

In the dissertation, which she had hoped to publish as a book one day, she described Winnipeg as an idyllic place to grow up, what with forests, rolling hills and a “swimming hole” serving as their playground.

“Each day was an adventure for the children. If we weren’t wading in the creek, trying to catch water skippers, crawdads or minnows, we might be making a dam in the creek with sawdust, and standing below waiting for the force of the water to break the dam,” she wrote. Games they participated in regularly were hide-and-seek, marbles and ante-over, the latter of which required two groups of kids to stand on opposite sides of a house, and heave a rubber ball back and forth, over the roof.

When she and her siblings weren’t frolicking about or attending school in Nelson, “about three-and-one-half miles from Winnipeg, over hill and dale,” they were helping their parents at the store and on the family farm. Her brothers were responsible for milking the cows, tending the fields and splitting firewood. She and her sister took care of the dishes, helped prepare meals and assisted with the laundry. There was also insect duty.

“In the summer flies flocked into the home in too big numbers to kill with a swatter, so two or three of us would get a cloth and start at one corner of the room and, waving the cloth high and fast, shoo or coax the flies out the front door,” she wrote, adding it was a great relief when flypaper came along in the 1940s.

Supplied The Lamkins home in 1952, along Winnipeg Drive.

Ultimately, Winnipeg was the victim of progress. Weaver wrote that “with better roads and cars” people began flocking to large towns such as Lebanon, 40 kilometres to the west, and Waynesville, 30 kilometres to the north, for their shopping needs.

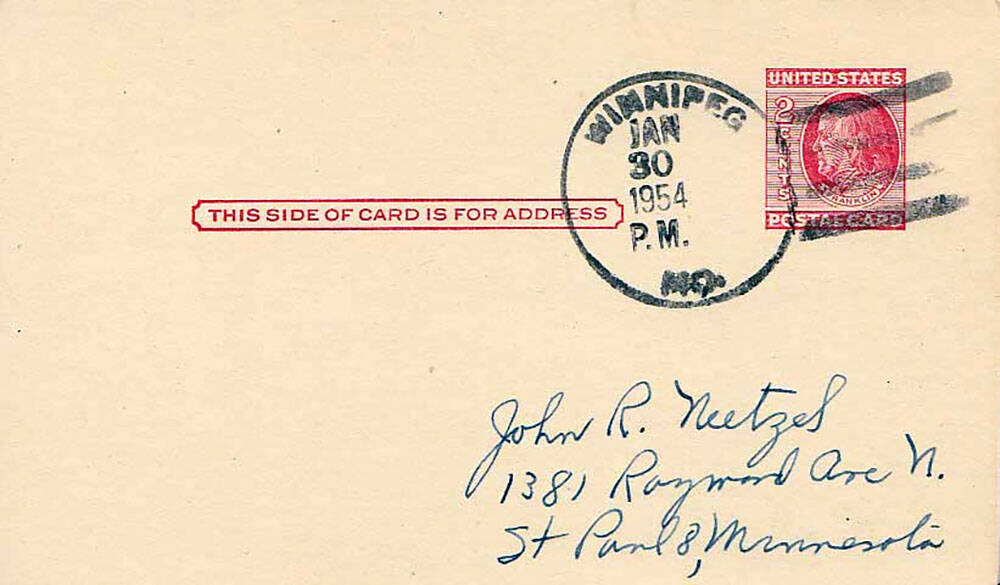

“As a result, the store finally closed and later, on Jan. 30, 1954, the post office,” she wrote, noting the community itself had disappeared from area maps by the 1980s.

Interestingly, the post office’s pending closure was reported in a human-interest piece in the Winnipeg Free Press in December 1953. The news caused local philatelists to spring into action, according to a followup story in the Free Press dated Feb. 5, 1954.

A postmark stamped the last day the post office in Winnipeg, Mo., was open for business.“Several stamp collectors in Winnipeg, Manitoba, made use of the hint by sending self-addressed envelopes to the postmistress with a request that they be cancelled on the last day of the post office’s operation,” the second story read.

As it turned out, Winnipeg (Manitoba) stamp enthusiasts weren’t the only ones licking their lips in anticipation of netting a rare specimen for their hoard.

Kelvin Kindahl, assistant curator of the National Postmark Museum in Bellevue, Ohio, asked, “Is this enough for your needs?” when he emailed us an image of an envelope addressed to a resident of St. Paul, Minn. with a postmark reading “Winnipeg, Mo. Jan 30, 1954 P.M.” in the top right-hand corner.

It would be difficult to find a greater authority on Winnipeg, Mo., than Dewayne Baker, a married father of two and grandfather of one who has lived a stone’s throw away from where Winnipeg once stood for 53 of his 63 years.

He was born in his grandparents’ house “over yonder,” Baker says, pointing past a herd of cattle that are contentedly munching away in a corner of his 400-acre property. “The way my mom Roberta tells the story, Grandpa and Grandma went to town to get groceries. When they got back, she’d had me, all by herself,” he says in a slow southern drawl.

His mother was single when he was born. She married a few years later but when she announced she was moving away with her new husband, he chose to remain behind with his grandparents, in a house close to where his great-grandfather John Baker, a Confederate Army soldier during the American Civil War, settled after the war ended in 1865.

David Sanderson photo Dewayne Baker in his shop.

There wasn’t much left of Winnipeg when he started to attend school in the late 1960s, he says, seated in his 2,000 square-foot-workshop, which along with his and his wife Nancy’s house, was rebuilt from the ground up in 2017, after a tornado destroyed their previous premises.

“There were a few houses here and there and if you wanted to go trick-or-treating you’d better have a half-gallon of gas. The store had closed, the mill was gone… so on and so forth,” he says, asking us to excuse his attire, which consists of sneakers, mud-stained overalls and a short-sleeve shirt, the sleeves of which he had pared off himself with scissors. It’s not that he didn’t dress for the occasion, he chuckles; truth be told, it’s the same “suit of clothes” he dons for church every Sunday.

“If you look at a map you’ll see there’s a tremendous amount of national forest around here (Mark Twain National Forest) and as people continued to move away, the government acquired their land, piece by piece.”

After completing Grade 12 in Plato, 25 kilometres away, Baker grew and sold Christmas trees, around holding various construction jobs. He and his wife were married in 1983 and subsequently moved to Nebo, 15 kilometres away. That’s where their two daughters were born.

“There were a few houses here and there and if you wanted to go trick-or-treating you’d better have a half-gallon of gas. The store had closed, the mill was gone… so on and so forth.”–Dewayne Baker

His grandmother, who was predeceased by Baker’s grandfather in 1982, died in 1992. Following her death, they moved into her house, close to Winnipeg, Mo. The family stayed there for seven years until Baker purchased a neighbouring farm, the one he and Nancy live on to this day.

Baker guesses he was in his early teens when he asked his grandparents if “their” Winnipeg was connected to Canada’s Winnipeg, in any way, shape or form.

“Grandpa gave me the story of that guy who came down here from Canada for whatever reason, and how it was him who gave it the name,” he says, flipping through photographs of himself taken when he was a youngster. “I never thought too much about it till I got older. I probably figured there were lots more Winnipegs out there, maybe in Colorado or Kansas, ’cept when I learned that wasn’t the case, that there were just the two, I laughed and thought ‘now that’s odd, ain’t it?’”

David Sanderson photo A marker at the Baker residence still stands along Winnipeg Road.

The Winnipeg area, which is bordered by the Gasconade River to the north, a popular swimming spot when Baker was a youth, is similar to its Canadian cousin when it comes to sense of community. Baker tells a story from before he was born, about his grandfather landing in a hospital bed for months, after being struck on the head by a falling tree limb.

The elder Baker fell behind on his mortgage payments while he was convalescing and ended up losing his home. Except when he was finally able to leave the hospital, he was met with a new, two-room house close to where he and his wife had been living that had been built for them cost-free, by their neighbours.

“It was the same thing after the tornado wiped out my place,” Baker goes on, noting he was in Colorado visiting his younger daughter, a television news anchor, when the storm struck. “That was on a Saturday and when I rushed home the next day to assess the damage, there were 30 or 40 people waiting for me on the lawn, who’d come from as far as 15 miles away. The first thing out of their mouths was (asking) what did I need them to do.”

In addition to managing 60 head of cattle, Baker, who will visit Canada for the first time this summer when he and a brother go fishing in Yellowknife, also runs a two-year-old woodworking biz that turns out live-edge furniture and heavy-duty cutting boards made from lumber — oak and ash primarily — he sources from his property. Winnipeg Custom Creations, the name he gave the venture, definitely draws its share of comments when he sets his booth up at farmers’ markets and craft sales throughout the state.

David Sanderson photo Dewayne Baker (right) and his wife Nancy show off the business sign for Winnipeg Custom Creations.

“People approach me and say ‘are you from Winnipeg?’ ‘Yep,’ I say, to which they respond ‘do you mean to tell me you drove all the way here from Canada?’”

That’s when he shakes his head no, and proudly informs them that he is from “Winnipeg, Missouri.”

“To a person they say they’ve never heard of such a place, and are shocked to discover it’s been here, in their own backyard, for over 100 years.”

Back at the cemetery, the sisters commend one another, saying “that’s far improved,” once they’ve finish sweeping and raking around the various headstones, and placing artificial flowers next to those bearing the name Lamkins.

They have a brother Dave but he isn’t the sentimental type, Taylor says, so it has seemingly fallen to them to maintain their relatives’ final resting places.

“I know our brother’s youngest is interested in genealogy, but I can’t say for certain if he’s ever even been down here,” Stiller says.

Taylor, in her mid-60s, laughs when asked if she can remember the first time she visited Winnipeg as a kid. (Their mother moved to Lebanon, Mo., after marrying their father, Thomas “Ted” Weaver in 1947.)

David Sanderson photo Winnipeg, Mo., is bordered to the north by the Gasconade River, which was once a popular swimming spot for local residents.

“We came every summer, usually when Aunt Goldie came to visit from Georgia, but what stayed with me the most was the time Uncle Bud threw me off the bridge into the (Gasconade) river, when I didn’t even know how to swim,” Taylor says. “The water was six-feet deep and thankfully my cousin Pam jumped in to rescue me.”

Stiller, in her early 70s, also has vivid memories of visiting their grandmother and grandfather, at their house steps away from what is now Winnipeg Drive. Often, she would curl up to take a nap before a late afternoon picnic, she recalls. Problem was, she always had trouble falling asleep, owing to an old cuckoo clock her grandmother kept on a living room wall.

“I can still hear the ticking sound it made; I swear, I can’t stand that kind of clock to this day,” she says.

As they put away their tools, the women are joined by Baker, who has driven over from his house in a golf cart. He wonders if they’ve visited what’s left of their grandparents’ general store yet. That’s where they are headed next, they respond. “Great, let me join you,” he says, instructing a border collie seated in the back of the cart not to move a muscle till he returns.

(Before making the 200-metre trek to the store, the four of us pay a quick visit inside the church, which is still utilized for weddings, baptisms and funerals. Taking a seat on an upholstered pew while the women snap pictures, Baker, who is part of the church’s advisory board, points out it only costs $100 to be buried at the Winnipeg cemetery. At that price, he should probably be outside, picking out a plot, he says with a wink.)

The general store circa 1970s (now abandoned).“There it is or at least what’s left of it,” Stiller says when we reach a section of the road directly opposite the store. What with the tremendous amount of tree and shrub growth that surrounds the wooden structure, it’s almost impossible from our vantage point to ascertain how much of it remains standing. When one of the sisters says she’s going to try and get a better look, Baker recommends she slip on a pair of knee-high rubber boots he brought along for that very purpose.

“This is southern Missouri and we have ticks, chiggers and poison ivy, things you may not have in Canada,” he says to his Canadian visitor. “The deal is, when you feel the chiggers go to itchin’ it’s too late, they’re already dead and gone.” (Uh, where did you say those boots are again?)

As the day goes along, and we call on a few other spots Baker, Stiller and Taylor remember from their childhood (“See that mound of dirt to yer right? That was Edmund Ott’s place. That rotted-out shack up the hill? That’s where Shorty and Charlotte Garrett lived.”) it’s sadly evident Winnipeg is but a shell of its former self. Venture a bit further afoot, though, and you will come across a half-dozen or so newer residents, Baker says.

David Sanderson photo Baker along with sisters Renee Taylor (centre) and Stephanie Stiller in church.

“There’s a guy bought the farm across the road from me, end of last year,” he says. “And off to the right, just after you cross the creek, you’ll see that somebody’s doing some building there, too. I was told it’s a fellow from Indiana who intends to put in a campground and cater to the deer hunters so I guess we’ll see.”

Stiller says the fresh activity reminds her of a paragraph near the end of their mother’s manuscript. Read it aloud, Taylor says. After all, wouldn’t it be fitting to allow their mother to have the last word in a story about her beloved Winnipeg?

“Nothing much is left now of ‘Old Winnipeg, except the church,” Stiller reads, from her mother’s script. “The ‘Old Winnipeg’ is now only memories, but who knows what the future holds for Winnipeg?”

“The ‘Old Winnipeg’ is now only memories, but who knows what the future holds for Winnipeg?”–Manuscript of Wanda Weaver

SIGN OF THE TIMES

You would be mistaken if you assumed Winnipeg Drive, the tree-shrouded, four-kilometre-long thoroughfare that runs past what was once Winnipeg has carried that moniker for over a century.

For years, the gravel road, which extends from Route 32 to the north to Dawn Road to the south was known simply as Road 32387, according to Dewayne Baker, whose proper home address is 18651 Winnipeg Dr.

Winnipeg Drive.“When the state introduced 911 service 25 or so years ago, all the roads around here needed a proper name,” he continues. “It just so fell that everything going north and south had to start with a W, for whatever reason, and when officials did some digging, they discovered this is where Winnipeg used to be, so why not call it that?”

That’s good to hear, Baker says, when we let him know the Winnipeg Drive sign was exactly where he told us it would be, on our way to his place. Apparently, the sign has become a collector’s item of sorts, and goes missing on a regular basis.

“There’s another Winnipeg Drive sign down the road a bit and I’ll bet you a dollar it won’t be there next month,” he says, adding “no, probably not” when we say, in our defence, “Hey, don’t look at us, Manitobans aren’t the ones taking it.

“Years ago there was gentleman from the area name of Herman Detherage who got a sign made for his front yard that read ‘Old Winnipeg,’” Baker adds. “Darned if somebody didn’t steal that, too.”

GETTING THERE

The driving distance from Winnipeg, Man., to Winnipeg, Mo., is 1,643 kilometres, not counting any sudden turns we were forced to take along Winnipeg Drive, to avoid running over painted turtles sunning themselves in the middle of the road.

We pulled out of our driveway at 8:30 a.m. on a Tuesday morning, and travelled along Interstate 29, once we’d passed through Emerson. Following pit stops for gas and/or sustenance in Fargo, N.D., Watertown, S.D., and Sioux City, Iowa., we spent the first night in Omaha, Neb., arriving there a little after 8 p.m.

We were back on the road at five the next morning. We reached Kansas City, Mo., during the morning rush hour — too early for barbecue, we lamented — where I-29 switches to Interstate 49 just south of the city.

We hung a left at Harrisonville, Mo., 60 km past Kansas City, and followed Missouri Route 7, then Missouri Route 5 to Lebanon, Mo., the closest urban centre to Winnipeg, about 30 km away.

We visited Winnipeg three times during our stay in Lebanon, which we were told by a motel manager is properly pronounced as “Leb-nin, two syllables.” We chowed down at a number of noteworthy establishments in Lebanon, most notably Dowd’s Catfish & BBQ, where a parking lot sign advertises it as the “home of the country’s best award-winning catfish.”

The intersection of Winnipeg Drive and Dawn Road.On Thursday, we had breakfast at Clifton’s West Side Café. The conversation at a six-seat lunch counter revolved almost entirely around Florida governor Ron DeSantis’s previous night’s announcement that he would be seeking the Republican nomination for the 2024 presidential election.

“DeSantis is OK,” a gent to our left announced to nobody in particular, while watching the news on TV, “but I still love Trump.” (According to state records, 82 per cent of the voters in Lebanon chose Donald Trump over Joe Biden, in the 2020 U.S. election. That didn’t come as a surprise as there were multiple front-yard signs along historic Route 66, near our motel, that declared, “Don’t blame me, I voted for Trump” in capital — er, Capitol? — letters.)

We headed back home on Friday, and drove 18 hours flat-out in an effort to make it back in time for a scheduled Saturday-morning softball match.

Between innings of the game, teammates asked what we’d been up to that week.

“Not much,” we replied with a wide yawn, “mostly just hung around Winnipeg.”

david.sanderson@freepress.mb.ca

Dave Sanderson was born in Regina but please, don’t hold that against him.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.