A dizzying bird’s-eye view of Alberta’s oilsands It’s the largest bitumen deposit in the world. Mining there is visible from space. And for many Canadians, the oilsands are still completely unseen

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/12/2023 (682 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

As soon as you arrive in the Alberta boomtown of Fort McMurray you can smell the oil — it’s like a sharp cousin to hot asphalt.

You can see it too — evidence of its extraction is visible in the few tailings ponds along the highway north of town, where plumes of exhaust drift, ever expanding above refineries.

By the numbers

They’re as expansive as the landscape.

• $35 billion in profits for six companies in 2022.

• $17 billion in government royalties in 2022, making it the largest source of revenue for the year.

• 3.3 million barrels produced per day.

• 81 million metric tonnes of carbon pollution in 2022 — the equivalent of burning 90 billion pounds of coal.

• 1,097 square kilometres mined, 0.1 per cent certified reclaimed.

This is the oilsands — the home of billions of barrels of tarry crude oil that lies under 142,000 square kilometres of northern Alberta, driving the local economy and bolstering provincial budgets.

But it’s not until you’re in the air that the scope of the oilsands becomes clear — a sprawling landscape teeming with enormous trucks outfitted with tires taller than two F-150 trucks stacked together.

As the sun rose over the frozen earth last winter, The Narwhal flew to see the oilsands mines.

On our way out of the city the pilot pointed to land cleared for a subdivision that hasn’t been built — a sign the booms of the past, when there were more workers than housing, might not come back.

Soon the pink-hued snow gives way to a moonscape where boreal forest is being scraped away.

Even then, it’s hard to grasp what you see.

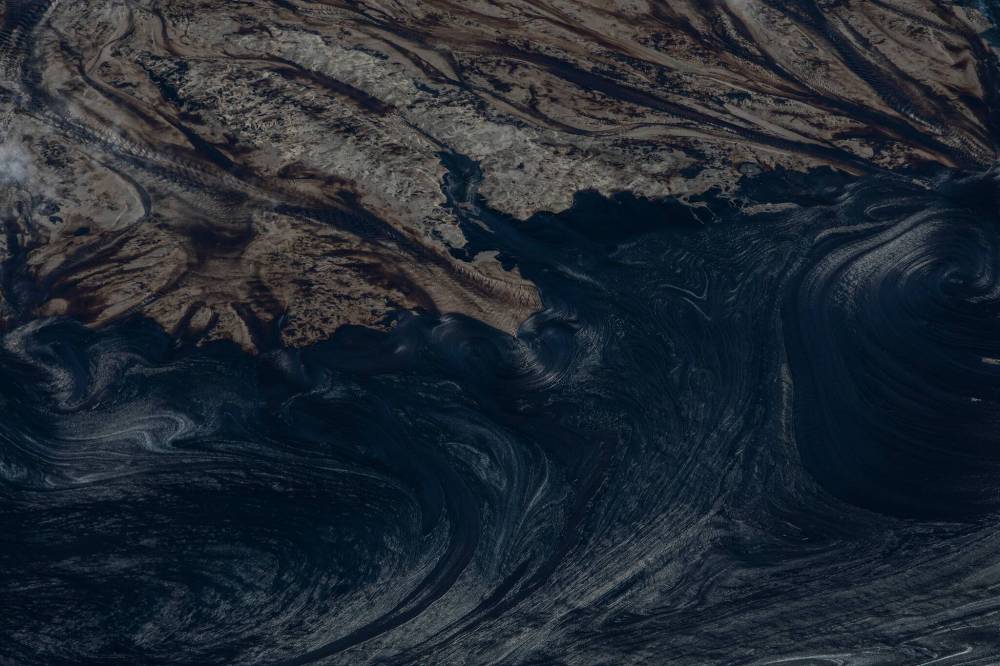

A tailings pond at a Suncor open-pit oilsands mine.

Off to the east, the Suncor Base Plant spreads pipes and tubes like fingers across a vast industrial complex, crawling with an average of 6,000 workers each day.

To the northwest are Syncrude’s Mildred Lake facilities, a similar maze of pipelines and stacks, where bitumen is diluted and upgraded before being sent by pipeline to refineries like those in Edmonton, some 500 kilometres away.

The scale is difficult to comprehend.

Reference points help — those enormous dump trucks are specks on the landscape, the buildings and trailers even smaller. It helps snap the mind into focus.

But that view encompasses only two of the eight oilsands mines currently in operation.

A tailings pond at a Suncor open-pit oilsands mine near Fort McMurray, Alta. If tailings ponds from all of the oilsands mines were combined, they would cover an area twice the size of Vancouver.

People had known about the oilsands for centuries before anyone started to think about ways to dig them up. In the 1950s, a plan emerged to detonate a nuclear bomb below the crude oil deposits.

That plan fizzled and in 1967 Great Canadian Oil Sands, now Suncor Energy, launched the world’s first large-scale oilsands open-pit mine.

The goal has remained the same in the decades since: extract the oily sand from below the surface. It’s then mixed with water and often chemicals and cooked in separators to release the valuable oil.

The resulting mix of sand, silt, clay, water, residual hydrocarbons and chemicals are dumped in clay-lined pits to settle.

There are lakes of mine tailings in various states — from young pits of muddy bitumen- and chemical-laden water, to mature tailings ripe with the glossy sheen of oil, to pits back-filled with sand for reclamation.

If you were to take all of the tailings ponds from all of the oilsands mines, they would cover an area twice the size of Vancouver, 300 square kilometres.

There are lakes of tailings in various states in the region.

They’re not really ponds — these industry-made reservoirs store nearly 1.4 trillion litres of byproducts from the mining of oilsands, including arsenic, naphthenic acids, mercury, lead and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

While there has never been a comprehensive federal study, many people believe these chemicals are linked to higher rates of rare cancers in nearby Fort Chipewyan (the Alberta government’s data shows “higher than expected” rates of bile duct cancer in the region).

The tailings ponds are ever growing. A recent analysis from the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society found Suncor’s Fort Hills oilsands mine expansion will add 60 square kilometres of new tailings ponds over the project’s lifetime — an area large enough to cover the island of Manhattan.

The analysis also estimated the mine will result in 732 million cubic metres — 300,000 Olympic swimming pools — of new tailings fluid.

Suncor Base Plant next to the Athabasca River north of Fort McMurray.

This is just a fraction of oilsands activity. Approximately 80 per cent of Alberta’s oilsands reserves are so deeply buried they can only be extracted through the much smaller footprint of what’s known as in-situ extraction, most often by pumping hot steam deep into the oil deposit with a technology known as steam-assisted gravity drainage. The infusion of steam melts the oil, allowing it to be drawn up to the surface.

But it’s the open-pit mines where the trees, muskeg and layers of earth are methodically removed — so deeply Niagara Falls could be tucked neatly below the surface.

The soil structure here has been forming for millions of years. It’s so ancient an oilsands worker accidentally dug up a 112-million-year-old dinosaur, Alberta’s oldest, at Suncor’s Millennium mine in 2011. Those layers are moved truckload by truckload, to get at the tar-like oil trapped in dirt.

Whether from open-pit mines or in-situ extraction, the resulting tarry substance is too viscous and not yet marketable.

Upgrading can involve making the bitumen less thick (converting it to what’s known as “dilbit”) so it can be transported by pipeline to refineries across North America.

Mature tailings ponds are ripe with the glossy sheen of oil.

Refineries essentially distil the oil into higher value petroleum products — like gasoline, diesel, lubricating oil and jet fuel.

The process brings tremendous wealth to the companies who produce it — depending on the price of a barrel — and the operations fatten Alberta’s budget in eye-watering ways.

For the fiscal year 2022-23, provincial revenues from the oilsands — including recovery from in-situ extraction that does not involve open-pit mines — amounted to almost $17 billion, the largest slice of Alberta’s financial pie for the year.

No matter your perspective, it’s hard to take it all in.

This article was originally published on The Narwhal.

Equipment storage at a Suncor site.

A tailings pond at a Suncor open pit oilsands mine near Fort McMurray.

Amber Bracken for The Narwhal

Suncor’s Fort Hills site in Fort Chipewyan, Alta.

The trucks are gigantic up close, but miniscule compared to the mine’s scale.

The Suncor base plant is located next to the Athabasca River north of Fort McMurray.