Conservation crippled by cuts Environment and climate advocates hope public pressure can prompt the province to take the department’s role in protecting natural assets seriously and to properly fund and staff it after years of neglect

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/09/2023 (815 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

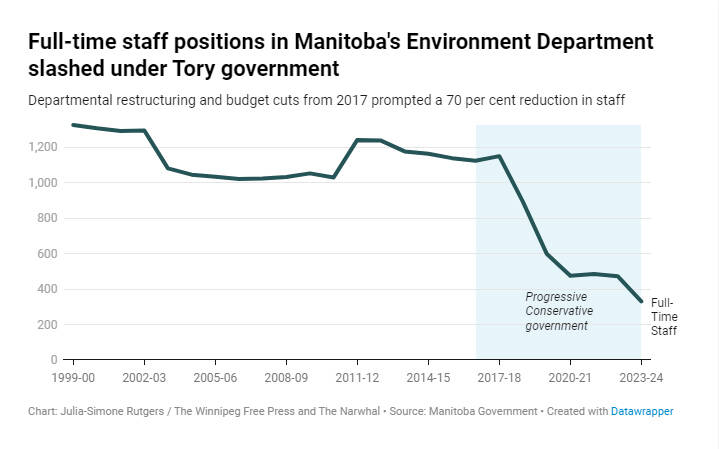

Twenty years ago, Manitoba’s conservation department, now the environment and climate department, was operating with more than 1,300 staff. Today that number has dropped by 75 per cent, to just 331 full-time positions — 20 per cent of which are currently vacant.

In addition to the severe staffing cuts, government branches geared at conserving and protecting the province’s natural assets have seen their funding stagnate, according to a Free Press/The Narwhal analysis of environment budgets since 1999. Those staff and funding cuts have only intensified since the Progressive Conservatives took office in 2016.

The austerity measures have left department staff “at the end of their rope” and put critical environmental services in jeopardy, said Mark Hudson, a sociology professor at the University of Manitoba.

Services such as environmental testing, monitoring and investigations have suffered as a result of cuts — since the Tories took power the average number of public complaints investigated has dropped by more than 70 per cent.

Despite growing concerns from environmental groups, the environment and climate budget has not attracted much attention during the current Manitoba election campaign.

“These are basic environmental protection services, and if they’re not being done, then the public is not being protected,” Hudson said.

Hudson’s academic career has focused on the relationship between labour and climate change. He and several of his colleagues at the University of Manitoba recently interviewed more than 2,000 public-sector employees — including 83 environment and climate staff — to understand how the last seven years have impacted job satisfaction and the ability to serve the public.

“It made for extremely depressing reading,” Hudson said of his interview transcripts.

“(There’s) the sense of demoralization, the sense they don’t have the support from government to do the job that they know the public demands, the sense that they are being asked to do way too much with too few people and too few resources — and with fewer resources all the time.”

In the 1999-2000 fiscal year — the inaugural year of the Gary Doer-led NDP government — the province had allotted more than $139.3 million (or $220 million in 2022 dollars) for its conservation initiatives, including managing provincial parks, fish and wildlife, water resources, forestry, fire response, energy policy and environmental stewardship.

By the time Brian Pallister’s Progressive Conservatives defeated the NDP in 2016, the budget had already been slashed by 25 per cent, and staffing was down to 1,100 employees.

This year, Manitoba budgeted just $134 million for the Department of Environment and Climate. Provincial parks, wildlife and forests have become the purview of the Department of Natural Resources — which has traditionally focused on economic development in Manitoba’s north — and environment services have been reduced to water management, climate change and biodiversity initiatives, waste regulation and environmental licensing. Staff have been cut a further 71 per cent.

According to a statement from an unnamed government spokesperson, there are currently 68 vacancies in the department, which amounts to 20 per cent of positions.

Environmental non-profits have seen their organizational funding reduced and some services, like park pass administration, park waste collection, air ambulance and fire services, and tree nurseries have been transferred to out-of-province private companies.

These cuts, Hudson said, have left a historically “mission-driven” group of staffers severely overburdened.

“They are caught between the extreme limits on the resources they have to do their jobs, the external demands of the public and their internal drive to actually do the job they got into the public sector to do — which is environmental protection, education and monitoring,” Hudson said.

The statistics are telling: 60 per cent of people surveyed for the study reported being asked to provide the same or more services with fewer resources; more than 90 per cent report worse working conditions and job satisfaction than in 2016; 90 per cent say worker recruitment and retention has been more difficult.

“They are having a hugely difficult time filling vacancies, turnover is very high and it’s leading to a huge deficit of knowledge and experience within the department,” Hudson said.

“It really paints a portrait of a key function of government that’s barely keeping its head above water, and in fact the only way it is keeping its head above water is by drowning the employees that do the work.”

Manitoba doesn’t publicize the number of vacancies across government services, but in March NDP natural resources critic Tom Lindsey tabled documents showing the province had only been able to fill 81 of 102 conservation officer positions. The 20 per cent vacancy rate was the lowest the province had seen for several years.

Historically the complement of conservation officers, whose long list of responsibilities include policing hunters and provincial park users, issuing and monitoring industrial work permits for park lands, investigating wildfires and dealing with problem wildlife, has numbered between 250 and 400 members.

The Tories responded by committing to a $5-million investment in wage increases and recruitment efforts to rebuild the conservation officer team. But Manitoba Government and General Employees’ Union president Kyle Ross told media at the time burned-out conservation staff were moving to other provinces in the pursuit of better pay and working conditions.

Hudson heard a similar refrain from employees across the sector, who have reported worsened mental health as a result of job pressures.

“(Employees) are within a workplace that feels — and I think objectively is — in crisis in terms of its capacity to do the environmental protection and conservation that it’s supposed to do,” he said.

“Those workers on the front lines are in a terrible place, and it’s clearly taking a toll on them.”

A shrinking staff complement for environmental protection takes a toll on Manitoba residents too. Growing public awareness of how climate change is impacting the province has led to public pressure for more timely and effective government response when calamities come to light.

But citizens at the forefront of grassroots efforts — like residents in Winnipeg’s contaminated Point Douglas neighbourhood or Springfield community members opposing a silica sand mining project that could contaminate their water supply — have felt ignored by the province.

In an interview this past summer, Point Douglas residents’ association president Catherine Flynn described having “fairly regular meetings” about heavy metal and lead contamination in her neighbourhood before the Tories took office, but “zero” progress or communication in the years since. She said email chains were dropped, questions went unanswered and promised air- and water-quality testing never materialized.

Tangi Bell, who leads the Our Line in the Sand campaign opposing Sio Silica’s proposed mine in the Springfield-area aquifer, described similar experiences having requests to test water quality or monitor mining exploration and test drilling go unanswered. She said in an interview her official complaints had been shuffled from department to department, but no solutions ever came.

According to departmental reports, Manitoba’s environmental compliance staff did not investigate any public complaints in 2022. Between 1999 and 2016, the department averaged 29 complaint investigations annually; since the Tories took power that average has dropped to eight.

Site inspections and monitoring activities have followed a similar trend, dropping from an average 200 inspections per year under previous governments to 111 annually since 2016. Last year, the province completed just 46 site inspections.

“If industry is not being adequately watched and if the laws are not being enforced by site visits, protection is not happening,” Hudson said.

There are currently 10 vacancies in the team responsible for environmental compliance, according to the government spokesperson.

Changing course will require a “huge influx of investment” in climate and environment programs — including an influx of staff, Hudson said.

Even if the government took immediate steps to rebuild its environmental services, he estimates it would take at least a decade to shore up the resources needed for effective protections.

But the steps to get there, he said, are simple: listen to staff members’ needs and ideas, prioritize filling vacancies, pay reasonable wages, put money into training (including post-secondary programs and on-the-job training), fund parks’ budgets to tackle the backlog of conservation and infrastructure work and keep those jobs in the public sector.

Ultimately Hudson hopes public engagement and pressure will prompt the province to take conservation more seriously, institute a whole-of-government approach to climate change and properly resource the public sector responsible for protecting the environment.

“The worldwide call for investment in these areas is deafening and we’re twiddling our thumbs in the midst of it,” he said.

julia-simone.rutgers@freepress.mb.ca

Julia-Simone Rutgers is the Manitoba environment reporter for the Free Press and The Narwhal. She joined the Free Press in 2020, after completing a journalism degree at the University of King’s College in Halifax, and took on the environment beat in 2022. Read more about Julia-Simone.

Julia-Simone’s role is part of a partnership with The Narwhal, funded by the Winnipeg Foundation. Every piece of reporting Julia-Simone produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.