Cries for help Michael Bagot’s family hoped the inquest into his death following an altercation with police would bring closure. Instead, they have more unanswered questions

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/12/2023 (694 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Four long years after her husband died following an altercation with Winnipeg police, Asha Bagot arrived at the first day of the inquest into his death with an open mind.

The confrontation began on May 21, 2019 with a string of 911 calls reporting a man behaving erratically.

The man, later identified as 40-year-old Michael Bagot, had grabbed onto an ambulance, ran through traffic and, fearful and paranoid, climbed onto a Winnipeg Transit bus near the intersection of Provencher Boulevard and Tache Avenue, repeatedly yelling for the driver to lock the doors because he thought a pedestrian’s cellphone was a gun.

At the inquest, Asha Bagot had been hoping to learn the officers who’d boarded the bus had done their best to manage her husband’s medical distress and de-escalate the situation. Had she seen that, Bagot said, “We would have accepted it. It would have given us a peace of mind.”

SUPPLIED Michael and Asha Bagot had been married seven years and had a one-year-old son at the time.

Those hopes evaporated last month when the court began playing a surveillance video of Michael’s last conscious moments.

When two officers enter the bus, their first words are: “Put your hands up.”

The video shows Michael popping his hands up immediately. But when an officer tells Michael to turn around, he asks them to wait.

The officers push Michael against a window and wrestle to get his hands into handcuffs. Michael says he wants to call his uncle and cries, “Please send an ambulance!”

More officers arrive and pull Michael down onto the narrow bus floor, with several piled on him. One sits on his legs.

Michael can be heard screaming for help before falling silent. Once he’s handcuffed and his ankles bound with a restraint called an RIPP Hobble, video shows officers carrying Michael’s limp form off the bus.

It would take about 10 minutes for medical help to arrive. At some point, he stops breathing.

Later, at the hospital, a physician told family members Michael’s brain appeared as if he’d been without oxygen for upwards of 10 minutes. He’d be taken off life support several days later.

“You know how hard it is to live with? To know that he suffered and nobody helped him?” said Bagot in a lengthy and emotional interview at her Winnipeg home, alongside two of Michael’s cousins, who also attended the inquest.

“Michael was literally screaming, ‘help!’”

The incident is being examined as part of an ongoing inquest into the deaths of five men, each following altercations with Winnipeg police officers.

The men — Michael, as well as Matthew Fosseneuve, Sean Thompson, Patrick Gagnon and Randy Cochrane — died over a roughly 12-month period beginning in July 2018. Several expert witnesses are set to testify when the inquest resumes in 2024.

The inquest, which is being presided over by provincial court Judge Lindy Choy, is not allowed to lay blame on any person or institution. Its purpose is to determine the circumstances of the five men’s deaths and make recommendations to prevent similar outcomes in the future.

Except for Cochrane’s, no other family is being represented by legal counsel.

With the evidence portion regarding Michael’s death concluded, his family is at a loss. What they can’t fathom is why police didn’t identify themselves as officers to Michael. Why they couldn’t have paused for a few seconds, patted Michael down, explained why they needed to handcuff him. Or, why medical assistance wasn’t at the ready when police engaged with him.

(The Independent Investigation Unit of Manitoba (IIU), the province’s police watchdog, had previously concluded no officer “caused or contributed to” Michael’s death.)

The Bagot family also questioned why police didn’t ask passengers to leave the bus, as a way of de-escalating the situation.

It was a thread Choy also picked up on. When she asked one officer why they hadn’t done so, he said he wasn’t convinced riders would have obeyed.

Though he was dealing with some mental health struggles, Michael had a stable, normal life, Bagot said. He had a business selling cars. Their son was less than a year old. He’d recently bought the family a tidy bungalow.

The pair had been married for more than seven years. Bagot grew up in Guyana and the pair met when Michael, who’d mostly been raised in Winnipeg, was in the small South American country visiting his relatives.

The official cause of Michael’s death was “anoxic brain injury with herniation; due to or as a consequence of cardiovascular arrest; due to or as a consequence of complications of cocaine toxicity.” While Michael sometimes used drugs, it was not every week, nor even every month, his wife said.

Whatever the reason behind it, his family agrees: Michael was not in his right state of mind that day in 2019 — and what he needed was immediate medical attention.

And the inquest itself, which Bagot, as well as Michael’s cousins — Emily Bagot-Sideen and Melanie Valladares — described as a “joke,” has brought more questions than answers. The three women raised multiple concerns, including over the lack of bystander testimony and police testimony that did not seem to align with video evidence.

The family members were also offended by inquest counsel, Crown attorney Mark Lafreniere, pronouncing their surname incorrectly at times and by what they saw as the inquest’s outsized focus on Michael’s erratic actions leading up to his encounter with police.

And they were taken aback by what they perceived as the friendly relationship between Lafreniere and Kimberly Carswell, a longtime lawyer for the Winnipeg Police Service. Valladeres described it as “two hands clapping.”

Four Winnipeg police officers, along with a CN police officer, who happened to be in the vicinity, a firefighter-paramedic and the bus driver testified at the fact-finding portion of the inquest examining Michael’s death.

Surveillance video from the bus, as well as video from a nearby business, was also played in court, while transcripts of IIU interviews with bystanders were tendered as evidence. None of the bystanders testified at the inquest.

Consts. Patrick Saydak and Ryan McCrady, followed by Staff-Sgt. Krista Dudek, were the first to encounter Michael on the bus. Saydak and McCrady moved quickly to try to handcuff Michael.

When Choy asked McCrady whether they could have given Michael more time to calm down, McCrady referred to his and the other two officers’ testimony — that Michael had yelled they weren’t real police — as one of the reasons he felt that strategy wouldn’t have worked.

Saydak testified he remembered talking to Michael, “trying to reassure him” and telling him he was with the Winnipeg police.

At no point in the bus video can the officers be heard identifying themselves, either by name or as the Winnipeg police. They repeatedly told Michael to “relax” as they struggled to restrain him.

“You could see, if this guy had a weapon of some sort it would have been pulled out already. He was just a terrified guy.”–Linda Sigurdson

It sounds as if Michael once said something like: ‘they’re not police,’ though a transcript that IIU investigators produced of the bus surveillance footage makes no reference to Michael having made such a statement.

According to the IIU transcript, Michael yelled “help” more than half a dozen times after police began trying to handcuff him; once on the ground, however, he quickly fell silent.

Passenger Linda Sigurdson told IIU investigators Michael did not appear to present a danger. She recalled the driver told riders they could exit out the back doors, but nobody did.

“You could see, if this guy had a weapon of some sort it would have been pulled out already. He was just a terrified guy,” she said, adding that the most aggressive thing Michael did was take a package from a shelf and throw it on the floor.

She then described a change in Michael: he went from yelling and screaming earlier on in the interaction with police officers — to being completely silent when restrained face-down on the floor.

“(The officers) all sort of, you know, had their knees on different parts of him,” Sigurdson said. “The guy was completely quiet at that point, like not — I don’t believe I heard another sound out of him.”

Supplied Michael initially puts his hands up but a scuffle ensues, resulting in several officers on top of his body.

Once officers carried Michael off the bus — in handcuffs and a leg restraint — and placed him on the sidewalk, they described him as yelling, thrashing and struggling. As aggressive, unco-operative and incoherent.

McCrady said Michael was in “non-stop motion.” Saydak initially said Michael was sometimes calm, sometimes screaming, including shouting ‘people were after him.’ Dudek recalled Michael saying that he wanted to stand up and was trying to do so. The officers said Michael was yelling and moving right up until nearly the exact moment firefighters arrived.

Bystander interviews with IIU investigators, as well as the surveillance footage from a nearby Pizza Hotline restaurant, detail a different scene.

That footage, which has no audio, shows a handcuffed Michael lying motionless on the pavement for about four minutes, with officers around him, one holding a rope from the restraint on his ankles like a leash.

When Michael’s legs start jerking up and down, the officers move closer, trying to hold him down and prevent his limbs from moving. Michael then appears to go limp again.

Officers testified Michael’s eyes started fluttering, prompting one to wonder aloud if he was having a seizure. They said they then moved him on to his side.

On this point, it’s not fully clear from the video what transpired. The top half of Michael’s body is mostly blocked by the positioning of an officer. It does appear he was rolled over at one point, though his feet remained as if he was in a face-down position.

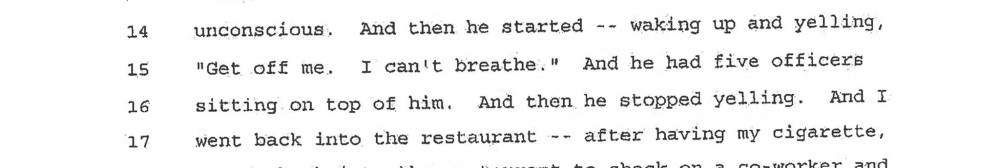

Miranda Irwin, who worked at the Pizza Hotline, told IIU investigators that from where she was standing outside the shop — about 15 feet away — Michael appeared to be unconscious when taken from the bus, as well as for some time when he was on the ground.

But at one point, Michael seemed to wake up and started yelling: “Get off me. I can’t breathe,” Irwin recalled.

She also said officers were “kneeling” on Michael.

Supplied Excerpt from bystander Miranda Irwin’s interview with the IIU.

Jeffrey Peters, the firefighter-paramedic who was the first medical professional to respond to the scene, told the inquest he saw an officer with a knee across Michael. In their testimony however, officers disputed that anyone kneeled or put weight on Michael once he was outside the bus.

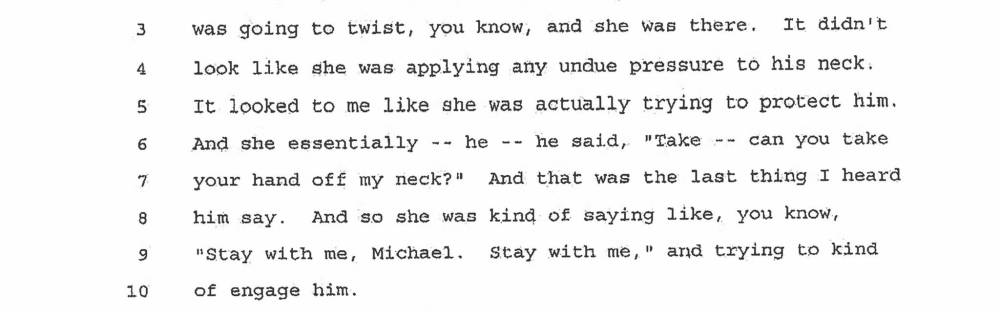

Ian Mauro, who was biking in the area, watched the entire chain of events outside the bus while standing approximately five feet away.

Mauro told an IIU investigator he watched a female officer holding Michael’s head, with one hand under his neck and one hand on top.

He said her positioning appeared protective — to prevent Michael from getting hurt — and she didn’t appear to be “applying any undue pressure to his neck.”

Mauro also told investigators that the last thing he heard Michael say was: “Take — can you take your hand off my neck?”

The female officer was saying to him, “‘Stay with me, Michael. Stay with me,’” Mauro recalled.

When medical help arrived, Mauro said a first responder asked police when Michael last moved.

“(One officer) he kind of said that, you know, ‘It was within like the past couple of minutes he was moving,’” Mauro said.

Supplied Excerpt from bystander Ian Mauro’s interview with the Independent Investigation Unit of Manitoba.

Watching the video footage from the bus wasn’t the first time Asha Bagot had seen Michael paranoid and afraid. And it was clear to her how scared he was.

“He probably needed some reassurance,” Bagot said. “He put his hands up right away. That tells you already, he’s complying.”

Melanie Valladares, Michael’s cousin, agreed. And instead of reassurance, Valladares continued, officers “bum-rushed him, they went right in for him … They didn’t try to talk to him. They didn’t try to reason with him. They didn’t try to find out what was going on.”

Supplied Asha Bagot showed this photo to Judge Lindy Choy while speaking at the inquest last month. “This is Michael on a regular day: well-dresssed, well-spoken, well-respected,” she told the court.

“The fact that they even tried to say that they communicated anything to him is shameless, because it’s a video — like, we saw it,” she said.

Valladares also took issue with the officers repeatedly telling Michael to relax.

“‘Relax’ as you’re taking my arm and twisting it behind my back and shoving me against a window,” Valladares said.

The family is questioning why police didn’t do more — such as checking Michael’s pulse or his other vital signs — to monitor him in the roughly 10 minutes between when an ambulance was called and arrived. Police testified they were watching his breathing.

“He is handcuffed and he’s got to RIPP Hobble on his legs. He cannot do anything. You’re responsible for his life,” Valladares said. “That includes making sure that he’s alive — not just looking at him and saying, ‘Oh, I saw his chest go in and out.’ … So what? He was barely alive?”

“Honestly, his whole court thing, it just feels like a joke. It feels unreal,” Bagot added.

As she spoke, Bagot got up to retrieve a list of questions from her kitchen counter, questions the family had hoped to see asked — and answered — during the inquest.

“You’re responsible for his life … That includes making sure that he’s alive — not just looking at him and saying, ‘Oh, I saw his chest go in and out.’”–Melanie Valladares

“Is it possible that the physical force used by the Police Officers caused the cardiac arrest and the anoxic complications?” one read.

The women believe the level of force applied to restrain Michael played a role in his death. And that change is needed in how police respond to medical distress calls.

With the fact-finding portion of the inquest largely done, the family is left without much hope for the recommendations.

Emily Bagot-Sideen said the only recommendation the inquest seems poised to make is for police to have defibrillators in their possession.

When asked if they had any recommendations regarding training, policy or equipment, officers mostly offered no suggestions, saying they wouldn’t change anything they or their colleagues did. A few officers raised the idea of having defibrillators in their vehicles; one constable suggested Winnipeg needs a detox facility that accepts people who’ve been using methamphetamine.

Michael’s family, meanwhile, hopes to see recommendations focus on de-escalation and the avoidance of excessive force by police, as well as on having civilian workers respond to crisis calls involving mental health and addictions issues.

SUPPLIED Bagot’s body was placed on the sidewalk outside the bus where he was initially motionless for about four minutes. When his legs started jerking up and down, officers moved in to hold his limbs down.

Bagot-Sideen, who is a social worker, referenced the need for a program where civilian teams composed of psychiatric nurses, paramedics, social workers and community-based outreach staff respond to crisis calls — instead of defaulting to police.

Such programs are operating or being piloted in a number of U.S. jurisdictions, such as Eugene, Ore., and St. Petersburg, Fla., as well as in Toronto.

“They already know the people in your community, they can talk to them and de-escalate them — and they’re not armed,” Bagot-Sideen said.

Bagot-Sideen said the inquest does not appear to be considering such possibilities.

“In an ideal world with appropriate life-saving services, what would have happened in that situation for Michael to have survived and to have gotten the help that he needed?” she asked.

As the three women talked about the incomprehensibility of Michael’s death, they also shared happy memories.

Valladares, remembering Michael’s “fresh to death” style — dark jeans and a comically long-standing preference for a particular drugstore cologne — put it this way: “Michael was everyone’s best friend.”

Supplied Michael Bagot and his bride, Asha.

Bagot remembered her early years in Canada, when she was working as a housekeeper at a downtown hotel. Michael would drive with her to work, pick her up for lunch and wait for her to be finished her shift. She also remembers the unexpected presents — a gold chain with her name written on it, wooden roses. Her picture in his wallet. Or that Michael had bought gold jewelry for his son before he was born.

Michael was a people person, they said. He worked hard. He’d supported people when they needed it, and gave them a chance when others wouldn’t. A week before he died, Bagot recalled, Michael had bought $100 of McDonald’s burgers and, with a young employee he’d hired, gave them out to people downtown who might be hungry.

“Everyone that met him had a story to tell because he was that type of person,” Bagot said.

Bagot pulled up a video on her phone. In it, Michael is waggling his head back and forth at his infant son, and making increasingly goofy sounds, seeming to delight in the response of his son’s tender laugh.

“(He) loves watching this video,” Bagot said, nodding towards her son, who, now five years old, was perched on a nearby couch, watching TV, his bedtime rapidly approaching.

Last month, on the second day of the inquest, Bagot had a chance to address Judge Choy. She brought up the yearning questions of her young son.

“I suffer every day trying to be strong for my son, who often asks, ‘What happened to my father?’” Bagot told the court. “As young as he is, he asks those questions.”

“What should we tell our children in situations like this?”

The Inquest Files

Under Canadian law, officers must believe their own life, or that of another, is fundamentally at risk — or at risk of “grievous bodily harm” — to use lethal force.

That scenario has played out 29 times in Manitoba since 2003, with Winnipeg Police Service responsible for 21 deaths, RCMP for seven and the Manitoba First Nations Police Service for one.

The number of fatal shootings involving law enforcement, both in Manitoba and across Canada, has increased in recent years.

The trend has intensified public scrutiny of police conduct. It is also raising questions about whether provincial inquests, which are mandatory following lethal shootings, are achieving their goal of exploring ways to prevent future deaths.

To find out, the Free Press put two decades of inquests into deadly encounters with a police bullet under the microscope.

Marsha McLeod

Investigative reporter

Signal

Marsha is an investigative reporter. She joined the Free Press in 2023.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.