It’s an image of Canadiana that’s as enduring as maple syrup or a moose: playing shinny on a local pond.

But climate change experts warn that legacy is being threatened by unpredictable winters.

We visit Minnedosa, Man., to take in the town’s Skate the Lake pond hockey festival, where participants of all ages partake in this winter rite of passage — one they hope won’t be on thin ice anytime soon.

Old-time shinny on thin ice? Frigid slice of Canadiana could melt away as warmer, shorter winters become new normal

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/02/2025 (317 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

MINNEDOSA — It had been a tough game for the boys from Brandon. A crushing 15-6 defeat in their first playoff matchup of the day left the Heritage Co-op team with one more chance to avoid last place in the tournament.

Not to mention the weather was an opponent all of its own, with air temperatures dropping to -30 C on the open expanse of Manitoba’s Minnedosa Lake, made even colder by the whipping winds.

Still, spirits are warm inside the heated, green canvas tent serving as the tournament’s makeshift locker room.

“It’s cold, the other team had a few more skilled players than we did today,” Brenden Chudley says, tongue in cheek, as his teammates slump onto a row of straw bales to unlace their skates and catch their breath.

“It’s fun, everybody’s here having a good time — and how often do you get to play pond hockey outside on the lake?” Chudley asks.

Things are more jovial — though no less frigid — just a few feet away, where Heritage Co-op’s opponents, the Integra Tires, crowd around one of a few ducts pumping warm air into the tent.

They’re excited about the win, but what’s really made the day special, participant Nick Cameron says, is the people.

“Everybody gets back for one weekend and they all have fun,” he says.

Like the Co-op crew, most of the Integra team is from out of town, but they grew up playing organized hockey together in Minnedosa.

They’ve come home for the February long weekend to take part in Manitoba’s largest pond hockey tournament: Skate the Lake.

Pond hockey is synonymous with Canadian winters: kids lacing up skates on a pond, lake, river or creek, to pass a puck around and shoot at a patchy net, or a gap between a pair of boots.

“For us to have this kind of ice in our veins and collective experience of outdoor sport and play in that context is unique and special,” Toronto-based sports ecologist Madeline Orr says in an interview.

“Nothing quite transcends like hockey, and part of that is shinny. It’s not by yourself, it requires community — and that’s the magic.”

Shinny is said to be a precursor to ice hockey, evolving in Canada out of a combination of Indigenous and Scottish ball-and-stick sports.

Even as hockey grew into an international phenomenon, the tradition of an informal pickup game among friends on a patch of wild ice remained at the heart of the sport.

Even hockey icons like Sidney Crosby have fond recollections of outdoor pickup games.

“(For) small-town Prairies … it’s a winter social activity,” says Tanis Barrett, part of the original Skate the Lake organizing committee.

There’s no doubt outdoor ice rinks provide a sense of community and an opportunity for people of all ages and backgrounds to learn a new skill, though it’s not as ubiquitous as it used to be, her husband, Wes, notes.

The decline in family farms has resulted in smaller rural communities and fewer opportunities for a bit of impromptu shinny.

“For most of these kids, they’ve never had this opportunity to play outdoor hockey,” Wes Barrett says. “Giving kids these kinds of opportunities is maybe a little bit of a look back in time.”

It’s not just the decline in rural populations that threatens the future of pond hockey.

While this year’s tournament, with nighttime temperatures dipping well below -30 C, wasn’t threatened by what are known as “lost winter days,” climate-change experts say these unseasonably warm days are becoming more common.

So too are more variable freeze-thaw cycles and less predictable snow cover, all of which could put an enduring image of Canadiana on thin ice.

Described as a homecoming, a town reunion and a big party by attendees, Skate the Lake has been a Minnedosa fixture since 2007, when a group of families came together to plan a unique fundraiser for the town’s minor hockey teams.

The Barretts remember their friends Dan and Gaylene Johnson mentioning Plaster Rock, N.B.’s annual shinny fest — dubbed the World Pond Hockey Championship — and asking: “Well, we have a lake, why don’t we use it?”

They recruited volunteers from the minor hockey community, gathered around the Johnsons’ dining-room table and set to work planning what would eventually grow into an annual tradition for the town of 2,700.

“We were lucky enough to be involved from the beginning and it’s been great to see,” Tanis Barrett says in a phone interview the week before the event.

“Getting to see my kids coming back as grown-ups is super satisfying.”

Under the glaring sun and unending winter-blue sky, Minnedosa Lake has a magic quality about it. Clusters of colourful ice-fishing shacks flank the makeshift hockey rinks; quaint cottages line the far shoreline.

The lake is only about six metres deep, and at 94 hectares it’s “in that Goldilocks correct size,” Tanis Barrett says.

It’s human-made, created in the early 1910s as a reservoir for the small hydroelectric dam that would eventually make Minnedosa just the second Manitoba town to generate its own electricity.

After the dam was phased out in the 1930s, the lake grew into a destination for swimming, camping, boating and picnicking. It gained some international fame in 1999, playing host to the rowing, canoeing and kayaking events during the Pan American Games.

That legacy carries on in the canoe clubs, kayak clubs and dragon-boat teams that use the lake through the summer months. Events like Skate the Lake offer the town ways to appreciate the lake in the winter, too.

“It gives people a connection to the community and to the water,” Wes Barrett says. “It’s just a great way to celebrate the winter.”

Wes Barrett says the last few years have come with more weather unpredictability.

It’s gotten windier in the shallow topographic bowl where the lake sits; it’s become difficult to predict how much snow they’ll have to work with.

One year the tournament had to be postponed because a windstorm had sent a military-grade tent erected for the event flying down the beach and mangled its metal poles.

Another year was so warm the ice turned into slushy puddles, and the afternoon games had to be moved into the town’s indoor rink.

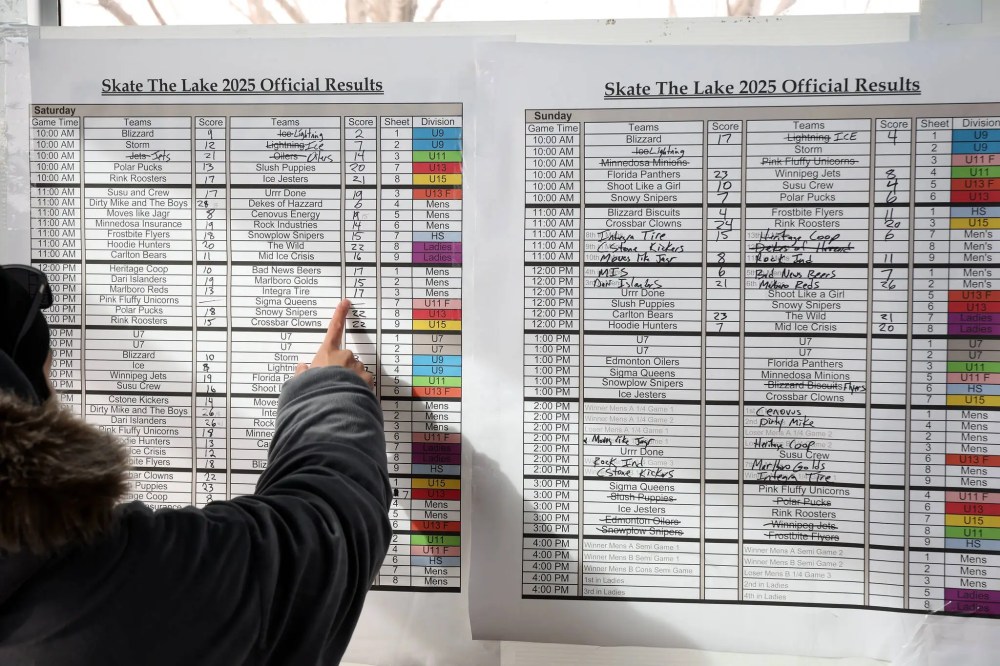

The tournament is contested on 10 snowbank-lined rinks, where four-player teams face off, without goalies, in 30-minute games, aiming to score on specially made goals just a few inches tall. There are separate round-robin draws for men’s, women’s and youth teams.

Everything is run by volunteers — mostly minor-hockey families who commit a few hours of the weekend to work the bar, serve food, maintain the ice or keep score.

About six years ago, organizers added curling to the weekend festivities and the Rock the Lake championship has been just as hotly contested (mostly just for fun) ever since.

As a bonus, organizers made room for what Wes Barrett calls the “over-60 crowd” to compete in the rousing stick-curling “pondspiel.”

Arlene Almey and her husband Nelson — competing under the team name Slide Show — are second-time competitors, popping in from their home across the lake.

Their daughter and son-in-law are curling this year, too. Arlene is 70, and despite the cold, she says, “it’s just as much fun” as the year before.

“I love when we have a grandma and grandpa curling, a mom and a dad playing hockey and then their kids,” Tanis Barrett says. “Three generations — that doesn’t happen very often with a sport.”

By mid-day, a misty fog has descended on the lake. There are only a few games underway; pucks snap against sticks, the ice groans as it shifts and the cheerful cacophony of kids at play drifts along with the wind.

Anthony Mousseau is standing at the side of one rink, frosty balaclava pulled up to his eyelashes, cheering as his six-year-old son, Ares, sporting a Winnipeg Jets jersey, fires the puck.

“Half the team are gone because they’re cold,” Mousseau says, his voice muffled behind the balaclava.

But Ares and the rest of the half-dozen under-sevens still on the ice don’t seem too bothered by the weather — they’re just thrilled to be playing outside.

“It motivates them, they want to go out. It gets them off the electronic devices — rare to see that these days,” Mousseau laughs.

In the tent, 10-year-old Nash Pomehichuk shrugs off the “pretty cold” conditions. This is the Minnedosa minor hockey player’s fourth Skate the Lake tournament, and the part he cares most about is spending the weekend playing among friends.

“You get to play against kids that you know,” he says.

Nash’s mom, Julie Pomehichuk, helped organize this year’s tournament — and played on the championship-winning women’s team, Mid Ice Crisis.

There’s something special about seeing “Canadian kids playing on the great big ODR (outdoor rink),” she says. “And our beautiful lake Minnedosa is the perfect spot for it.”

The ODR tradition, so dear to Canada’s cultural identity, could be under threat, research warns, and the global hockey community — from pond-hockey enthusiasts in Finland to even the NHL — has been sounding the alarm.

In Minnedosa, despite this year’s event being “colder than we’ve seen for the last several years,” Tanis Barrett says, a month ago, organizers were more concerned about the heat than the cold.

An unseasonably warm December meant the ice on the lake was too thin for town staff — typically in charge of initial ice clearing — to break out the heavy equipment needed to prepare the rinks.

The ice was eventually prepared in stages and only completed after colder weather arrived a few weeks before the event.

It’s the mark of a trend seen across Canada and the rest of the global north: warmer, shorter winters are becoming more common and the outdoor skating season is shrinking as a result.

“We’ve lost, in every part of Canada, somewhere between 20 and 40 skateable winter days in your average season,” Orr, the sports ecologist, says.

The most glaring example is Ottawa’s Rideau Canal, a popular skating spot for locals and tourists alike, which has lost about a week’s worth of skating days every decade since the 1970s.

The longest-ever skating season on the canal was 91 days in 1971. In 2022, for the first time ever, it didn’t open to skaters at all.

Closer to home, Winnipeg’s Nestaweya River Trail was only open for skating nine days last winter due to unseasonably warm temperatures.

It takes at least three days of temperatures below -5 C for ponds, lakes and even backyard rinks to harden enough to safely support skating enthusiasts, Orr says.

As Canada feels the effects of climate change — warming at double the global average — those sustained cold spells are fewer and farther between.

“The data that we have uniformly shows that access to natural ice is really steeply declining since the 1990s,” she adds.

Researchers at Wilfrid Laurier University have run a citizen science tool, called RinkWatch, to track conditions on North America’s outdoor rinks for the last decade.

The team’s latest report found the winter of 2023-24 was “one of the most challenging and unusual” since the project began, with frequent freeze-thaw cycles and unusually warm early winter weather leading to shorter skating seasons and “especially treacherous” ice conditions across the country.

Climate Central found more than one-third of northern countries, including Canada, lost, on average, at least a week’s worth of winter days (defined as days between December and February where temperatures fall below 0 C) each year in the last decade.

Coastal cities in British Columbia, as well as some parts of Ontario, lost upwards of two weeks of winter days in the same time.

While Manitoba’s typically frigid climate has experienced fewer losses than other regions (Winnipeg lost just one winter day per year), the trend across the global north is worrying for winter sports.

Orr explains hockey participation has been on a downward trend in recent years, in part because it’s an expensive sport made more costly by rising fees to access indoor ice.

“There’s not really an option to play outdoors anymore in the same way that there would have been in generations past, where, yes, there was an indoor rink, but if you were under the age of 10, you probably were playing outside,” she says.

“The middle class is getting squeezed out of this sport.”

Orr spoke to Winnipeg-raised former NHL player Colin Wilson for her latest book about the impacts of a warming climate on sport.

Wilson remembered honing his hockey skills on ponds and backyard rinks, she says.

Now, he worries Canada could lose its competitive edge as a hockey nation as the next generation loses access to those extra hours on the ice.

“Shinny, historically, is a bit of an equalizer in the sport of hockey,” Orr says. “It’s the accessible, low cost, low equipment version of the game.”

Back in Minnedosa, most attendees are taking shelter from the extreme winter weather inside the beach pavilion, a cosy, glass-walled room with a panoramic view of the ice below.

The room is heated — courtesy of the event’s propane sponsor — and outfitted with a small bar and canteen. Hundreds of people stop by the pavilion throughout the weekend, squished in shoulder to jersey-clad shoulder around rows of folding tables.

Volunteers stand over steaming crockpots piled high with smokies, pulled pork, baked potatoes and handmade perogies.

“As a family event, it’s pretty amazing,” Laura Lamb, the canteen co-ordinator says. “It’s something that brings our community together, but it’s also proof to me that it is an amazing place to live.”

In the midst of the action, Jared McNabb flits between the scorekeeping boards in one sunny corner of the room and a small public-address speaker in another. He’s the tournament’s draw master, in charge of timekeeping, tallying up scores and tracking each team’s progression through the championship.

It’s his first year in this volunteer position, but far from his first time in a starring role at Skate the Lake.

McNabb says he can’t remember exactly what year he first played, but “chances are,” it was the inaugural tournament. He was part of a team called the Burgess Quality Dudes, which had, in his words, “a fair bit of success in this tournament.”

From a quick count of the names engraved on the winner’s trophy, the Dudes, as they’re called, won the very first event — and then 10 of the next 15.

The team has collected a closet’s worth of the custom jerseys the town designs each year for the championship-winning teams.

“We kind of figured the game out,” McNabb laughs during a brief break between matchups.

“You’ve got to be ready to pass the puck around and deal with some conditions that aren’t 100 per cent between ice and weather, but it’s about having fun and being with your buddies.”

Now that he’s hung up his own skates for the weekend, McNabb is cheering on his two sons as they compete in under-nine and under-seven games.

“They had a blast and they were happy to be skating on the lake,” he says.

julia-simone.rutgers@fresspress.mb.ca

Julia-Simone Rutgers is the Manitoba environment reporter for the Free Press and The Narwhal. She joined the Free Press in 2020, after completing a journalism degree at the University of King’s College in Halifax, and took on the environment beat in 2022. Read more about Julia-Simone.

Julia-Simone’s role is part of a partnership with The Narwhal, funded by the Winnipeg Foundation. Every piece of reporting Julia-Simone produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.