Better odds for better lives on the outside Minnesota’s re-entry court boosts ex-inmates’ chances for success after release; a recent report decried the lack of such supports in Manitoba

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/04/2025 (234 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It took two bullets for Diontre Hill to rethink his life.

When he regained consciousness in a Minneapolis hospital bed three days after being shot in the back and stomach, Hill was able to summon a single phone number out of his fog.

Nearly four years later, he still doesn’t know how he remembered that number, the one that connected him to his re-entry court mentor.

Hill was six months out of prison when he was shot in August 2021, after serving a five-year sentence in federal prison for conspiracy and felony possession of a firearm, and 11 months in state prison.

The 31-year-old grew up in Minnesota’s justice system, spending time in juvenile detention facilities for gang violence and robberies.

The shooting made Hill think about his two sons, one 14 and the other nine months old — and how he didn’t want them following his path.

“If I kept going, in the next five years I would’ve been dead or in prison,” he says.

SUPPLIED Diontre Hill with his mother Trinicia Hill during his reentry court graduation.

In that hospital bed, with four tubes pulling fluid from his stomach, Hill’s mentor walked him through re-entry court over Zoom.

Once his hospital stay ended 22 days later, he found a job through the program as a line cook at a pub and decided to move his family out of Minneapolis and away from the violence that surrounded him.

“If it wasn’t for re-entry court, I’d still be in prison just because I would’ve never had nobody take that chance on me,” he said.

Minnesota’s federal re-entry court started in 2015. It’s an optional program offered to inmates being released and beginning probation who are flagged as high risks to reoffend.

Participants have access to a litany of resources, including addictions treatment and mental-health supports, to help them restart their lives. They’re also assigned a mentor to walk them through the 18- to 24-month program.

If they successfully graduate from re-entry court, their probation period is reduced by one year.

There’s no such program in Manitoba.

In late March, Manitoba auditor general Tyson Shtykalo flagged significant shortcomings in the province’s strategy for reintegrating inmates into society.

Shtykalo criticized the provincial government in his report for having “vague and rudimentary” plans for people leaving correctional facilities.

He said inmates are “on their own” upon release, left with simplistic instructions such as “quit drinking” or “stay sober — follow conditions” and “stay out, don’t get caught.”

He called on the province to do more to prepare inmates, which, in turn, will improve public safety and reduce recidivism.

In 2013, Minnesota’s federal justice system was at a similar crossroads. Judges were watching the same people cycle through their courtrooms and reoffend after serving their sentences. Probation officers continued to see the same people violating their release terms and being sent back to prison.

Odell Wilson, a now-retired federal probation officer, saw how people at high risk of reoffending were being set up to fail because they didn’t have the resources and support they needed to succeed on the outside.

GLEN STUBBE / MINNESOTA STAR TRIBUNE Judges Susan Richard Nelson and Donovan Frank listened as U.S. Probation Officer Reggie Hall discussed a case as the group gathered for a preliminary meeting with probation staff.

“You don’t have as much time to support them (as a probation officer), in terms of, even verbal encouragement,” Wilson says.

Wilson, who was aware that the re-entry court program was being used in other states, including Oregon and Massachusetts, drafted a report to start a re-entry court in Minnesota and pitched it to three federal judges. The judges were interested, he says.

A federal judge, prosecutor and public defender, along with a mental-health and addictions specialist, a community resource worker, a mentor and the participant’s probation officer make up the re-entry court roster, says U.S. District Court Judge Susan Nelson.

All, except the probation officer, volunteer to serve on the court.

Despite having similar weighty caseloads, everyone is willing to give their time because they believe the special court is making a difference, says Nelson, who presided over the program until 2023.

“Nelson credits the court’s success to the program’s mentors — they can connect with participants on a personal level that judges and lawyers often cannot.”–Diontre Hill

“There’s lots of things I do that are valuable as a judge, but probably nothing as valuable as this, to be honest,” she says, adding that re-entry court helped her become a better jurist.

The court strives to give people all of the resources they need for life outside of prison, Nelson says, citing supports for addictions, mental health and employment.

If someone violates their probation — by using drugs, for example — re-entry court will help them get proactive treatment rather than punishing them, she says.

Since 2015, the court has had 173 participants, and 44 per cent have graduated, according to data from the Chief U.S. Probation Officer for the District of Minnesota. There are, currently, 22 active participants.

Re-entry court takes place in a courtroom, but instead of a judge behind the bench, everyone gathers in a circle.

When Hill attended for the first time, he was caught off guard when judges asked about his well-being. And when he realized they were volunteering their time, his respect for them grew even more.

“When you hear ‘judge,’ it’s usually means court. It’s bad shit,” says Hill. “But I got judges in my phone. I could call (Judge) Susan Nelson and just have a conversation.”

Nelson credits the court’s success to the program’s mentors — they can connect with participants on a personal level that judges and lawyers often cannot.

Erik Washington, who works full-time driving dump trucks, has been a re-entry court mentor since 2015, helping 50 people over that time.

When he got out of prison in 2011 after serving a two-year sentence, Washington knew he wanted to give back so others wouldn’t make the same mistakes as he did. A friend suggested he should try mentoring for the special court.

“I wasn’t looking for any money. It is about saving lives,” says Washington, 62.

He began having weekly meetings in his mother’s dining room with other men who had been recently released. The group quickly outgrew the space.

“What I realized was a lot of these people were doing what they do because there was nothing else to do, and they didn’t know anything else, and nobody was showing them something else,” he says.

SUPPLIED Erick Washington and his wife Tammi

In 2021, Washington and his wife Tammi launched the Kingsmen Project, a non-profit for mentoring people leaving prison, with funding from the U.S. District Attorney’s office.

The project works alongside the re-entry court.

The Kingsmen Project operates from two locations: Washington’s basement and the cab of his dump truck when he’s on the road. He’s connected his mentees with jobs and provided rides to get them to appointments, if needed.

Washington also runs weekly Zoom calls with other mentees across the country on Sunday mornings, helping them navigate their journeys and keeping each other accountable.

He’s hosted barbecues attended by both judges and re-entry court graduates. On Thanksgiving, he opened his home for mentees who had nowhere else to go for a holiday meal.

Even though re-entry court has helped people get jobs, Washington says housing remains one of the biggest barriers that the program needs to address. Many have no option beyond a halfway house, where there can be temptations to reoffend.

He says he’s working to get funding for the Kingsmen Project to build its own transitional home so people can have “one less thing to worry about” when beginning their new lives.

Former provincial court Chief Judge Raymond Wyant has never seen anything like re-entry court tried in Canada.

But he has no doubt that it can be successful.

“I think its brilliant to have people who’ve been through the system before who aren’t just wearing a shirt and tie, for lack of a better term, but who’ve been there, who’ve done that, who’ve lived a life of crime, volunteering,” says Wyant.

“I think that, for an inmate, it would be incredibly important to have that kind of peer support.”

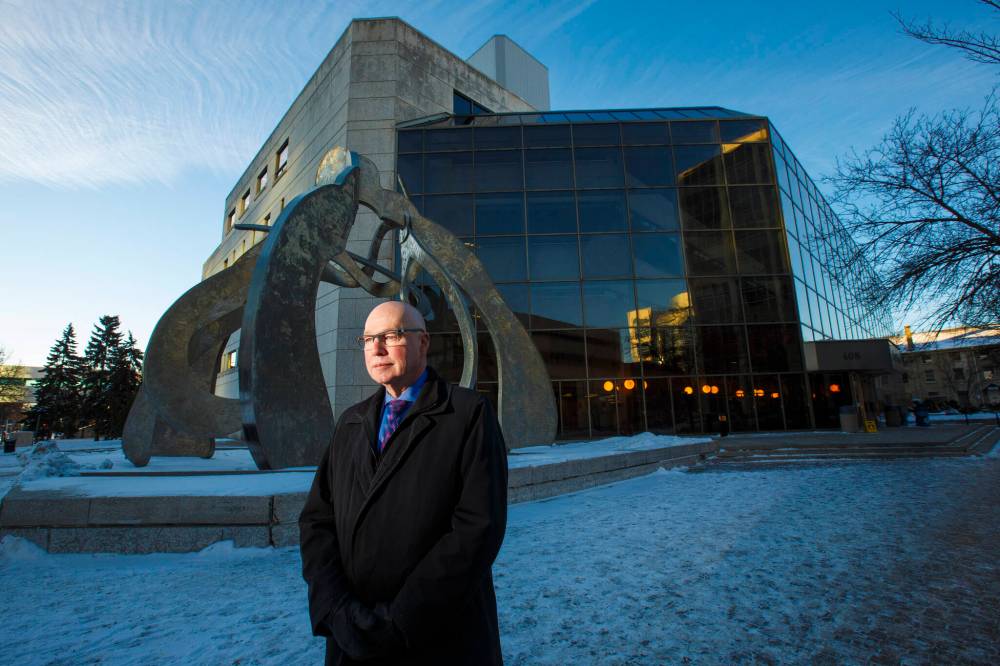

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Former provincial court Chief Judge Raymond Wyant

Nobody gets better in jail, and unless effective resources are offered for reintegration, it often feels like the current situation is only delaying an inevitable return to a jail cell, he says.

When he was on the bench, it was difficult seeing the same people return to his courtroom after serving their sentences, he says.

Wyant acknowledges there is no perfect solution but says new approaches, such as the Minnesota model, should be tried even if they achieve only moderate success.

“If you can save a life, you can save a victim, and you can save all sorts of things as a result of that,” he says.

In Manitoba, parole officers are the primary supervisors and connections for resources when an inmate leaves Stony Mountain Institution, the province’s only federal prison, on conditional release after a sentence of two or more years.

When inmates are preparing for reintegration, they’re assessed on their needs and how a plan can address things such as criminal history, mental health and education level, a Correctional Services of Canada spokesperson said in an email.

The province is working with community organizations, municipalities and First Nations to bolster transition services and establish and support sober centres.

Once release is granted, parole officers often help offenders get government ID, such as a driver’s licence, find housing and search for jobs. The parole officers are also responsible for referring people to community resources for mental-health or employment supports.

Community organizations, including The John Howard Society of Manitoba and the Native Clan Organization, also assist parole officers in finding housing or addictions treatment for their clients.

Offenders sentenced to less than two years are a provincial responsibility. Manitoba Corrections staff work with inmates to create release plans, including shelter options and getting access to IDs, a provincial spokesperson said in an email statement.

The province is working with community organizations, municipalities and First Nations to bolster transition services and establish and support sober centres where culturally relevant services are available, the spokesperson said.

No other details were provided on how transition supports are increasing.

Leif Jensen, a supervising lawyer for Legal Aid Manitoba’s Prison Law Clinic, says people who are on federal parole often don’t have a release plan tailored to their needs.

GLEN STUBBE / MINNESOTA STAR TRIBUNE Judges Susan Richard Nelson and Donovan Frank gathered for a preliminary meeting with experts before they all begin the week’s session of re-entry court.

When one parole officer is tasked with being the sole connector for crucial resources, it’s difficult to make sure adequate help is there, Jensen says.

“The only consistent thing we know is that that one person is going to be overburdened,” he says. “They’re going to have too many clients to manage.”

A program like Minnesota’s re-entry court would be more effective than the current parole system, he says, because it would give parole officers more alternatives when dealing with people who are high risks to reoffend without the burden falling solely to them.

“Right now, if someone fails a urine analysis, or if there’s a dispute where there might be a problem but there may not be, there aren’t very many options other than sending them back to jail,” Jensen says.

People aren’t usually locked up again on a first offence — it’s up to the parole officer’s discretion, Jensen says — but he’s heard from inmates who have voluntarily admitted to using drugs and were put back behind bars, which can delay any positive progress.

“If we’re not funding measures that are shown to be effective in reducing recidivism, then that means that’s not a priority, and it’s unfortunate that instead, we’re spending billions of dollars on penitentiaries,” Jensen says.

In 2017, the province launched the Responsible Reintegration Initiative to help inmates get settled in the community. But as of 2023, only 46 people had accessed the program, the auditor general said in his recent report.

Shtykalo’s report laid out 10 recommendations, including giving inmates a consistent point of contact while in jail and when they’re released into the community.

When he heard about Minnesota’s re-entry court, provincial court Chief Judge Ryan Rolston drew similarities to Manitoba’s alternative programs, such as drug-treatment and mental-health courts.

Community courts bring social resources together in one place, much like re-entry court, so people can access treatment and other supports and, possibly, avoid jail time.

They divert people away from traditional proceedings to more tailored approaches for treatment and monitoring.

Rolston says there are parallels with community courts, something that’s used globally and in Canada, though not in Manitoba. A community court works to divert people from the courthouse, so they are able to stay in their communities.

Community courts bring social resources together in one place, much like re-entry court, so people can access treatment and other supports and, possibly, avoid jail time.

But those systems are built to divert people away from entering the traditional justice system, not for those who are leaving it.

“It wasn’t really on my radar to sort of look at doing a re-entry program, because we’re usually doing things on the front end rather than on the back end,” says Rolston.

While he thinks the Minnesota program is valuable, Rolston says there would be some potential barriers to overcome if Manitoba implemented something similar.

For example, judges don’t issue parole requirements for sentences in excess of two years, he says.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS Provincial Court Chief Judge Ryan Rolston

That’s handled by the Parole Board of Canada, which means legislation would have to change, allowing judges to cross jurisdictional lines to see offenders after sentencing.

But Rolston says he appreciates the level of involvement judges have in the Minnesota system and adds that he’s seen similar success with the province’s alternative courts, which are overseen by judges.

“For some reason, it seems to have a lot of impact for the participants,” he says. “It’s that person in authority who’s giving, in most cases, words of encouragement.”

However, he cautions that setting up a similar re-entry court would also increase already-strained workloads.

His preference is to see Manitoba’s current alternative courts expanded to offer more services. Rolston says he also hopes a community court will be set up, something the provincial government has promised to do.

Manitoba was a national leader under previous NDP governments in creating new approaches for courts and supporting them, Justice Minister Matt Wiebe says. He wants to restore that position.

“There’s a lot of pressures on our courts, and they’re doing great work, but ultimately it’s about finding success for those reoffenders, or those folks where you see that recidivism, Wiebe says.

“We need to find real, novel solutions.”

A Manitoba-specific solution is necessary for success after looking at programs in other jurisdictions, he says.

The province is working with judges on how to implement those solutions — and to set up a community court — he says, but provides no timeline for its creation.

fpcity@freepress.mb.ca