The northern front Manitoba poised to become a hub for increased efforts to assert Canada’s Arctic sovereignty

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

A key part of Canadian Maj.-Gen. Chris McKenna’s job is assessing and analyzing threats from around the world. And, right now, he sees adversaries on the horizon.

“I worry about both Russia and China, separately and for different reasons. Russia specifically is the acute threat. China is a pacing threat,” he says.

By pacing threat, McKenna means China is the long-term, primary competitor facing the United States and Canada. It’s a view shared by many with more hawkish or “realist” leanings.

“They are now (both) pushing their way into the Arctic — very quietly, but there remain threats from both sides.”

Canadian Armed Forces Image Maj.-Gen. Chris McKenna, commander of the Canadian Norad Region based at CFB Winnipeg.

McKenna is speaking from Canadian Forces Base Winnipeg, a gated community of training schools, barracks, runways, hangars and military facilities practically the size of a university campus co-located at the city’s airport.

It employs thousands of people and is the operational headquarters of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

McKenna is the Commander of Canadian Norad Region, 1 Canadian Air Division (1-CAD), Joint Force Air Component Commander and Commander of Search and Rescue Region Trenton, all of which have CFB Winnipeg as their home.

Effectively, this means he oversees operations on all flying missions in Canada and around the globe.

This includes the Griffon helicopters and Hercules airplanes that airlifted thousands of residents from communities afflicted by the Manitoba wildfires this year. It includes operational support for NATO for missions in Ukraine and much more.

McKenna carries his intricate authority with casual confidence.

Affable and informal, the two-star general looks little like the authoritarian cigar-chomper popularized as an archetype by films like Patton and A Few Good Men.

“He’ll probably ask you to call him ‘Chris,’” says one of his colleagues. You’ll hear the general calling those around him “buddy.” He may seem a fittingly Canadian model of the modern major-general.

Though, when he starts talking about adversaries and Arctic geopolitics, he grows steely.

McKenna is a key figure in northern military matters at a time when the North feels unusually politicized and the discourse of “Arctic sovereignty” more in vogue.

Aviator Nicholas Zahari, 17 Operations Support Squadron Imaging, Winnipeg Members of the Royal Canadian Air Force and the Canadian Army assisted with wildfire evacuation efforts in The Pas earlier this summer.

A time when rising geopolitical tensions — not just with China and Russia, but also its longtime ally the U.S. — inspire a push, for better or worse, toward more manoeuvring and military infrastructure in the Arctic, with climate change potentially opening up trade routes and access to critical minerals and other resources.

A time when water crises, power outages, forest fires and other natural disasters afflicting Canada’s North continue to lay bare its often tragic vulnerabilities — while demands for greater social infrastructure and Indigenous sovereignty also intensify.

All of this complicates an expression like “Arctic sovereignty,” a buzz-term you’ll hear repeated by Prime Minister Mark Carney and his office.

But the ground is shifting, the ice is melting and our city and province appear poised to play a role worth considering in this uncertain new era of Arctic politics. Not only because of CFB Winnipeg’s role and reach, but because of Manitoba’s unique social, medical and economic relationship to Nunavut.

Winnipeg’s reputation as the “gateway to the North” positions it to assume new and renewed meanings in the coming decades.

Baby boomers may recall Norad’s reputation in the Cold War as North America’s alarm system.

A network of watchful radars, sensors and satellites offering a first line of defence against a Soviet bomber flying over the Arctic or missiles sailing over the North Pole toward Washington, D.C., or Ottawa.

To younger generations, Norad is probably best known as the “Santa Tracker.” Every Christmas Eve, it reports on St. Nick’s status as he travels the world dropping off toys.

Despite its diminished place in military thinking post-Cold War, Norad, established in 1957, remains the pillar of the military’s North American airspace defence and monitoring activities.

The binational partnership, with overarching headquarters in Colorado Springs, Colo., also plays a key role in military efforts to identify maritime threats. It does so by analyzing an amalgamated picture of the sea and potential threats lurking in it, like ships or subs that might fire a missile at North America.

Aviatrice Riette Bacon photo American F-16 jets (above) and Canadian CF-18 Hornets.

Though it often lights up in exercises, the Combined Aerospace Operations Centre — Norad and the Royal Canadian Air Force’s nerve centre, which has the top-secret, gadgety feel of a command centre from a Tom Clancy movie — is in a quiet state of monitoring much of the time.

About a month ago however, it was abuzz. A man had hijacked a Cessna 172 plane in Vancouver and was flying towards that city’s international airport. Could this be a possible terrorist attack?

“My air-op centre… gets it flagged that this is a non-compliant track, and it leads us down a path of convening, essentially, a conference to discuss what we’re going to do about this track of interest,” McKenna says.

F-15 jets were scrambled from Oregon and Canadian CF-18 Hornets readied for backup. Ultimately, the F-15s never crossed the border and it was decided there was no need for the Hornets to take flight.

“(It) was quite apparent quickly, one light aircraft hijacked, or stolen, and you’re in a law-enforcement path,” says McKenna. In other words, the conference did not adjudge the situation as a terrorist or national-security threat and concluded the matter could be treated as a local law-enforcement issue.

Norad operations such as these are largely a product of the post 9/11 era.

After the Cold War, a less glamourous view of Norad echoed in security circles. Norad wasn’t just a Santa Claus tracker, it was “SNorad,” having apparently outlived its utility in a unipolar world where American supremacy was unchallenged.

For obvious reasons, the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks shifted this outlook for many, bringing added scrutiny to potential internal airspace threats and beyond.

These days, Canada, the U.S. and NATO are back to staring unblinkingly at their Cold War adversaries, Russia and China — and at the sky for rogue spy balloons, fighter jets and missiles assembled in Siberia or Qinghai.

They’re watching the Arctic intently too, as they always have.

While long seen as a region of high co-operation and low conflict, things changed after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Russia began to more actively modernize its military capabilities in the Arctic around 2007.

“The most urgent and important task we face is asserting Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic and northern regions.”–Prime Minister’s Office

It’s intensified these efforts since 2022, while all the other member nations of the Arctic Council, Canada and the U.S. among them, have boycotted diplomatic meetings involving Russia. It’s also ramped up Arctic oil and gas exploration.

This provides the backdrop for Canada’s new defence vision, Our North, Strong and Free, released by then prime minister Justin Trudeau and federal defence minister Bill Blair last April.

“The most urgent and important task we face is asserting Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic and northern regions,” stated the Prime Minister’s Office at the time.

Our North, Strong and Free announced a new overall investment of $8.1 billion over five years — with Canada’s defence-spending-to-GDP ratio expected to rise from 1.37 per cent in 2024-25 to five per cent by 2035 in line with its NATO commitments. The government has also pledged $38.6 billion over 20 years to help modernize Norad.

An immediate priority is the Arctic Over-the-Horizon Radar, a significant upgrade that is poised to allow Canada to peer farther into the void and sound alarms with more lead time, as perceived or potential threats creep down from the North.

The federal government has said it would reach initial operational capacity by the end of 2029.

Norad modernization is a hot-button topic these days.

Some see it as vital as the world slides back towards a “great-power competition” and the Arctic becomes more politicized.

Others are bound to view it and Canada’s unprecedented military spending as promoting brinkmanship — a “defensive” gesture that serves to antagonize countries like China and Russia.

Military historian and University of Calgary Prof. Alexander Hill, for instance, writing in June for Canadian Dimension, argues that “a dramatic increase in military spending” is based on the “nebulous notion of Russian activity in the Arctic” and fear-mongering that “Russia is out to get ‘us’ — the ‘us’ being NATO members.”

Such views are common among Canadian critics of the military and hawkish foreign policy approaches.

While some don‘t view it as cause for significant concern, defence boosters argue Norad risks trailing behind in critical respects as faster, more fearsome warfare tech is constructed and reaches international markets.

Norad detected a Russian intelligence and surveillance plane near Alaska in late August. But its 40-year-old North Warning System of radars can struggle to detect high-altitude threats, such as a Chinese spy balloon that flew over North America in 2023.

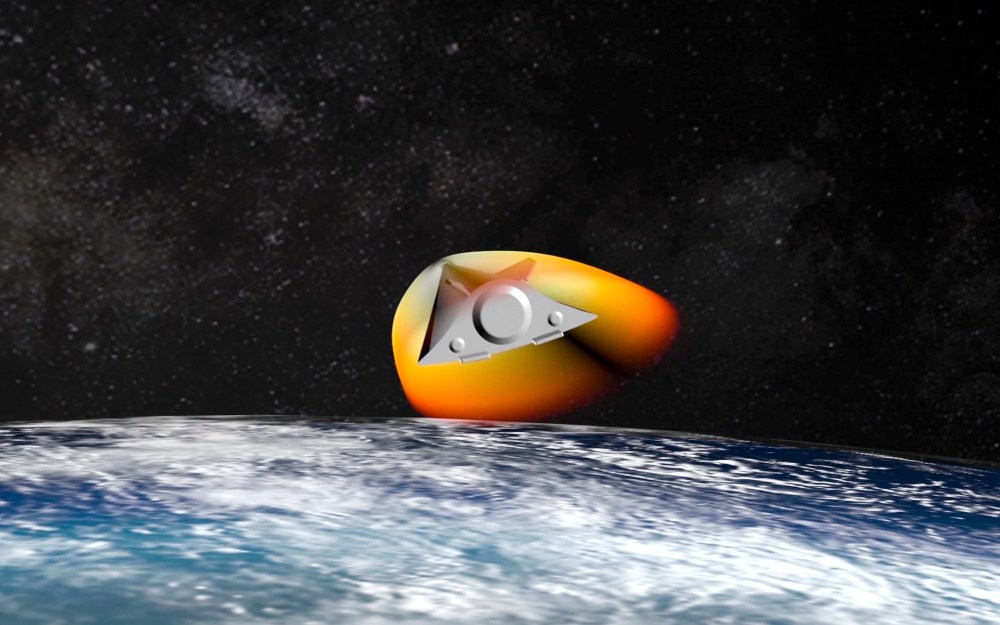

Russian Television / The Associated Press File A computer simulation on Russian television showing the Avangard hypersonic vehicle that Russia claims can bypass missile defenses en route to its target.

Meanwhile, national undersea surveillance systems simply aren’t designed for under-ice terrain. For now, they’re not much good for catching nuclear subs skulking around the Arctic Circle.

McKenna says he’s especially concerned about hypersonic weapons, a burgeoning issue for the military establishment. Not only do such weapons travel at higher than Mach 5 speeds (five times the speed of sound; roughly 6,000 km/h), they can change course mid-flight.

“Historically, we’ve sort of honoured the bomber — or the bomber that was going to shoot air-launched cruise missiles, or as we call them, ALCMs. That was our primary threat,” says McKenna.

“(But) the adversary could launch a Mach 5-plus weapon or launch it orbitally, in the sense that it leaves the Earth’s atmosphere, orbits the planet a couple times and can conduct a re-entry.”

Hypersonic speeds, tight manoeuvrability, orbital bombardment — these are the sorts of mixed capabilities that, it’s worried, could sail right past NORAD’s “nets.”

For these and other reasons, it’s not surprising some liberals and conservatives call not just for NORAD upgrades, but for a new integrated missile-defence system.

It’s dubbed the “Golden Dome.”

The future air-and-missile defence shield for the U.S., outlined in a January executive order by President Donald Trump, has an expected cost of US$175 billion and a build-time of three years.

“As a work in progress, these figures might make sense to link systems to defend the highest-priority critical assets — but it won’t yet produce a unity of effort,” says Prof. Andrea Charron.

Mark Schiefelbein / The Associated Press The U.S.’s ‘Golden Dome’ missile-defence shield is projected to cost US$175 billion.

Charron is the director of the University of Manitoba’s Centre for Defence and Security Studies and co-author of NORAD: In Perpetuity and Beyond, one of the “go-to” scholarly books on Norad, with James Fergusson.

“Trump tends to portray (Golden Dome) as this one single, exquisite system that’s going to be all singing and dancing. In fact, it’s going to be a whole bunch of different systems linked together,” says Charron. “And (the) Norad mission is a big part of that, because Norad has the air-warning mission for all of North America.”

McKenna describes a strong ongoing relationship with his counterparts within the U.S. Norad command structure: “I understand the (geopolitical) friction, but I do not live it in my day-to-day.”

Notwithstanding, such friction now surrounds the future of Golden Dome.

Trump recently demanded Canada contribute US$61 billion to funding the defence system — or nothing at all if we agree to become the 51st American state.

While Norad modernization is treated by its champions as key to U.S.-Canadian defence, upgrading Canada’s northern military infrastructure also evokes another agenda. One that also results in friction between the two nations: “Arctic sovereignty.”

In Canada’s national-security context, the fashionable term means asserting control in an increasingly accessible and contested Arctic. A final frontier, where Russian subs prowl, Chinese trade routes have been pursued and even the U.S. sometimes disputes Canada’s dominion.

“This is probably a sleeper issue that most people haven’t paid attention to in the last number of years,” said former Conservative Party of Canada leader Erin O’Toole last February.

“We were obsessed about COVID and didn’t really see what the first Trump administration did with respect to our Arctic sovereignty.”

David Goldman / The Associated Press Files A researcher aboard the Finnish icebreaker MSV Nordica as it traverses the Northwest Passage through the Canadian Arctic in 2017.

He was speaking at the elite Manitoba Club for a Canada West Foundation event, whose bold description urged Canadians to start defending northern borders “instead of waiting for the inevitable Tweet.”

A key theme was the Northwest Passage, which is at the heart of an old sovereignty dispute.

Canada insists it’s under its dominion while the U.S. maintains it’s an international strait — a position that, especially in the era of Trumpian nationalism, stokes worries about a potential scramble for effective control over the area.

A small number of cargo ships have braved the perilous passage since 2013. Still, some speakers pitched it as a viable trade corridor, banking on a warming climate to pry open the icy strait and expand its narrow summer window for travel.

Climate models tell a tougher story — especially when stacked against Churchill’s Arctic Bridge route, which stands a better chance of remaining ice-free.

Courtesy of the Town of Churchill Canada’s northernmost deepwater port in Churchill appears to be stirring to life after the federal and Manitoba governments have infused millions of dollars into reinvigorating the port and its railway.

That fledgling corridor, stretching from the Hudson Bay to Europe, is drawing more attention and scrutiny these days, anchored by Canada’s northernmost deepwater port in Churchill.

The port appears to be stirring to life, after going dormant due to railway line flooding and dwindling shipping contracts.

In recent years, the federal and Manitoba governments have infused millions of dollars into reinvigorating the port and railway. Earlier this week, Prime Minister Carney teased more announcements about upgrades to Churchill’s port.

He does so after successfully campaigning earlier this year on a nationalist platform that promised major new infrastructure projects to fight the economic fallout from Trump’s tariffs against Canada.

Both the port and the railway are owned by Arctic Gateway Group (AGG), a limited partnership between First Nations and 41 Bayline communities, including Churchill.

The AGG plays into the fashionable discourse, touting Churchill, which hosts one of Canada’s longest runways, as a boon to Arctic sovereignty and to future military operations, surveillance and search-and-rescue missions.

But the main hope is that the port might become the main re-supplier for Nunavut’s Kivalliq region — cutting costs in the territory, where shortages of food, fuel and resources are a constant reality — and establish a rejuvenated trade corridor from the Prairies and Arctic to overseas markets.

It’s a dream that’s drawn strange bedfellows — hinting at adjacent tensions surrounding the Arctic sovereignty project.

Earlier this summer, Prairie politicos got together at the Western Premiers’ Conference.

Two conservative leaders with western independence sympathies, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith and Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe, stood with Manitoba’s NDP Premier Wab Kinew championing brave new ideas about Prairie economic corridors.

Nathan Denette / THE CANADIAN PRESS FILES Manitoba Premier Wab Kinew, left, talks with Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe at the Canadian premiers meeting in July.

Ports on the West Coast and Hudson Bay could link Western Canada directly to overseas markets on the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

Earlier this month, the three Prairie premiers held talks about signing a memorandum of understanding to explore a new west-east pipeline. But Kinew, who clearly prioritizes northern development, was hesitant.

Last April, Kinew and Nunavut Premier P.J. Akeeagok signed an agreement to collaborate and press the federal government for funding on the Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link.

This would entail a 1,200-kilometre transmission line running from Manitoba that would bring clean hydro power, along with high-speed internet, to communities in Nunavut’s Kivalliq region that currently rely on diesel fuel for electricity.

But when it came to the west-east pipeline, Kinew ultimately tapped the brakes, saying more Indigenous consultation was necessary first.

“Spending a bit more time” on major infrastructure projects “(is how) we’re actually going to be able to maintain a true nation-building approach,” he said.

While Canada is strategizing about how to embolden its dominion of the North and lock arms to rebuff foreign interventions, our country’s Arctic sovereignty discourse is hardly a consensus.

It’s complicated not only by the diverse actors it seeks to rein in, but also by the questions it raises about what infrastructure and development should be put first: military, social or economic.

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS University of Manitoba professor and director of the Centre for Defence and Security Studies, Andrea Charron, is an expert on Norad.

Precedent warns against rashly conflating these priorities.

During the Cold War, Inuit communities were promised a chance for a better life through Arctic relocations and military projects. But new jobs were often menial and hunting opportunities in new areas scarce, and the government has since formally apologized for forcibly separating and relocating Inuit groups and killing their sled dogs.

Charron is an advocate of Norad modernization and an integrated missile-defence system. But she doesn’t want all this to sideline other pressing priorities for the North.

While she’s been somewhat skeptical of the Arctic Bridge’s long-term viability as a major trade corridor, she says “With the expansion of the Churchill Port, I hope the first consideration is to improve re-supply to Arctic hamlets.”

Despite the advances the Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link would bring to the Arctic, it’s a region where roads often remain unpaved, water is recurrently undrinkable and infrastructure lags decades behind.

“Civilian infrastructure in Canada’s Arctic is lacking. If Canada doesn’t see this as an imperative, it opens the door for foreign actors to provide that infrastructure for communities — and it also opens Canada up to potential security concerns,” she says.

For these and other reasons, many see “Arctic sovereignty” as a problematic prism through which to view for the North’s most urgent issues. Its overtones too militaristic and nationalist.

“Indigenous peoples have specific rights. They have sovereignty — on their data, on their resources, on the decisions that can be made in their territories.”–Andrea Charron

“When Trump started to talk about invading Canada and making Canada the 51st state… I think Indigenous people knew what was coming. We knew it was coming in the form of pipelines in the West. We knew it was coming in the form of Arctic sovereignty in the North,” Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, a Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, recently said in an interview with The Breach.

“The people that are going to pay the price are Indigenous peoples.”

Charron is critical of the term too. “Arctic sovereignty is used as the catch-all for ‘insert your concern here,’” she says, a symptom of what she calls “ADD,” meaning “Arctic distraction disorder.”

“But the Indigenous peoples have specific rights. They have sovereignty — on their data, on their resources, on the decisions that can be made in their territories.”

They call it the milk run.

A multi-stop air route between Winnipeg, Churchill and Arctic communities like Rankin Inlet in Nunavut that circulates passengers, mail and essential goods.

Bulk supplies flow northward from Winnipeg, often via Arctic Co-Operatives Limited and the Northwest Company, both headquartered in the city. Meanwhile, Arctic seafood, furs, natural resources, art and thousands of Inuit people are Winnipeg-bound every year.

Nastania Mullin, CEO of the Manitoba Inuit Association, says 20,000 Inuit travel annually to Winnipeg from Nunavut’s Kivalliq region for medical reasons alone.

SUPPLIED Manitoba Inuit Association CEO Nastania Mullin grew up near a military base in Resolute.

The association helps to accommodate these transplants and other Inuit in Winnipeg by assisting with housing and EIA applications, promoting financial literacy, and providing legal and mental-health support and other resources. It also undertakes archival research, Inuit consultations and ground-penetration work in connection with missing Inuit children and the legacy of residential schools.

It’s a lot to oversee for the relatively young organization, established in 2008, and it keeps Mullin’s focus sharp on the here and now.

But the CEO, who was trained in Indigenous law and raised near a military base in Resolute Bay, often thinks about the Arctic’s shifting political terrain.

Last year, Mullin travelled to Alaska, where the Arctic Encounter Symposium was held, and Greenland to discuss Indigenous exchange and economic sustainability with Inuit leaders from Greenland, the U.S., Canada and other Arctic nations.

“In (Manitoba Inuit Association president) Michael Kusugak’s famous words, ‘There is no Inuit word for ‘weapon.’’ So, it just goes to show our level of diplomacy,” he says.

Mullin speaks about how Arctic nations have used the Inuit as pawns in their geopolitical schemes and believes Canada has much to do to build equitable relationships with Indigenous communities.

But he’s hopeful about projects like the Port of Churchill revival and the Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link and speaks with pride about the many Inuit who participate in the Canadian Rangers, a 5,000-strong crew of reservists serving as the Canadian Armed Forces’ “eyes and ears” for the northern territories.

Canada’s “nation building” has to make room for a more sovereign and prosperous Indigenous North, Mullin believes.

“You’ve got to find that balance between cultural identity, cultural preservation and economic development,” he says. “(And) if you’re going to talk about Arctic sovereignty, you need to include Inuit at the forefront, at the beginning. Otherwise, we’re not going to going to buy it.”

McKenna also speaks to the relationship between national-defence priorities and northern community and infrastructural needs.

“In Inuvik, we have a shared facility with the community for fuel. But if I take too much fuel because I’m in some sort of defensive fight, I will cripple that community… we monitor the fuel levels at all of these places, like, to the litre,” he says.

“I’m not going to apologize for being a force of last resort for the government. We need to be lethal… that’s maybe tough for some Canadians to get their head around.”–Maj.-Gen. Chris McKenna

He projects optimism for the future — reinvestment in Arctic infrastructure, he argues, contrary to others’ misgivings, will not only serve military needs, but also those of northern communities.

But when it comes to Canada’s defence agenda in the North, the major-general speaks sharply, suggesting that — favour it or not — militarization of the North isn’t going away.

“I live in the air domain, so I’m executing missions in the Arctic, which are probably not super-tangible to the Arctic people. They don’t necessarily see us. We’re at 30,000 feet intercepting, like, maybe an amorphous threat that they wouldn’t necessarily perceive because it’s all high and far away. I understand that. My challenge is, I need to offer a credible, persistent deterrence to our adversaries who wish to do this continent and this country harm,” he says.

“I’m not going to apologize for being a force of last resort for the government. We need to be lethal… that’s maybe tough for some Canadians to get their head around.”

conrad.sweatman@freepress.mb.ca

Conrad Sweatman is an arts reporter and feature writer. Before joining the Free Press full-time in 2024, he worked in the U.K. and Canadian cultural sectors, freelanced for outlets including The Walrus, VICE and Prairie Fire. Read more about Conrad.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, August 29, 2025 9:53 AM CDT: Corrects reference in photo cutline to American F-16 jets

Updated on Friday, August 29, 2025 11:52 AM CDT: Clarifies reference to $38.6 billion over 20 years