Cornering the captive market Texas-based firm commands 80 per cent market share of telecom services for provincial and territorial inmates after securing non-competitive, highly lucrative contracts

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Six years ago, at a spring meeting of Manitoba’s jail superintendents, plans were getting underway to start providing electronic tablets to inmates in a few correctional institutions — with the company set to supply them making an attractive deal to the province.

Synergy Inmate Phone Solutions, Inc., a small, San Antonio-based company, would provide the tablets at no cost. All the necessary wiring and charging stations would also be provided, according to meeting minutes summarizing the April 2019 discussions.

The tablets would have access to games, movies and a monitored messaging platform, and would eliminate physical mail, explained Ed Klassen, then the director of operations for Manitoba Corrections, according to the minutes.

Unlike a Facebook Messenger or email account, which are free for the general public, this would cost 10 cents per minute — or about $13.50 with tax, to watch a two-hour movie.

And there would likely be another benefit to the province.

At that point, Klassen told the group, the province was already making between $6,000-$8,000 in commission each month from its existing contract with Synergy, which had been providing telephone services in Manitoba’s jails since 2016. Adding tablets to the offerings seemed set to increase that figure.

In 2021, the province requested proposals for the roll-out of tablets inside Manitoba’s jails, as well as the provision of phone services. It’s unclear what the province sought in its Request for Proposals, as anyone wishing to view the materials was required to sign a non-disclosure agreement.

In the end, the incumbent, Synergy won the contract handily: it was the only entity to download the proposal documents from the procurement website used by the province.

In the United States, Synergy is a bit player in a roughly US$1.4-billion-per-year-prison-telecom industry that includes an expanding set of offerings, from phone calls and video visitation, to tablet-based entertainment and electronic messaging, to money-transfer services.

In 2021, Synergy held less than a dozen small jail contracts, mostly in Texas, serving around 800 inmates at a given time, according to U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) filings.

But in Canada, Synergy has come to dominate this niche — and growing — market.

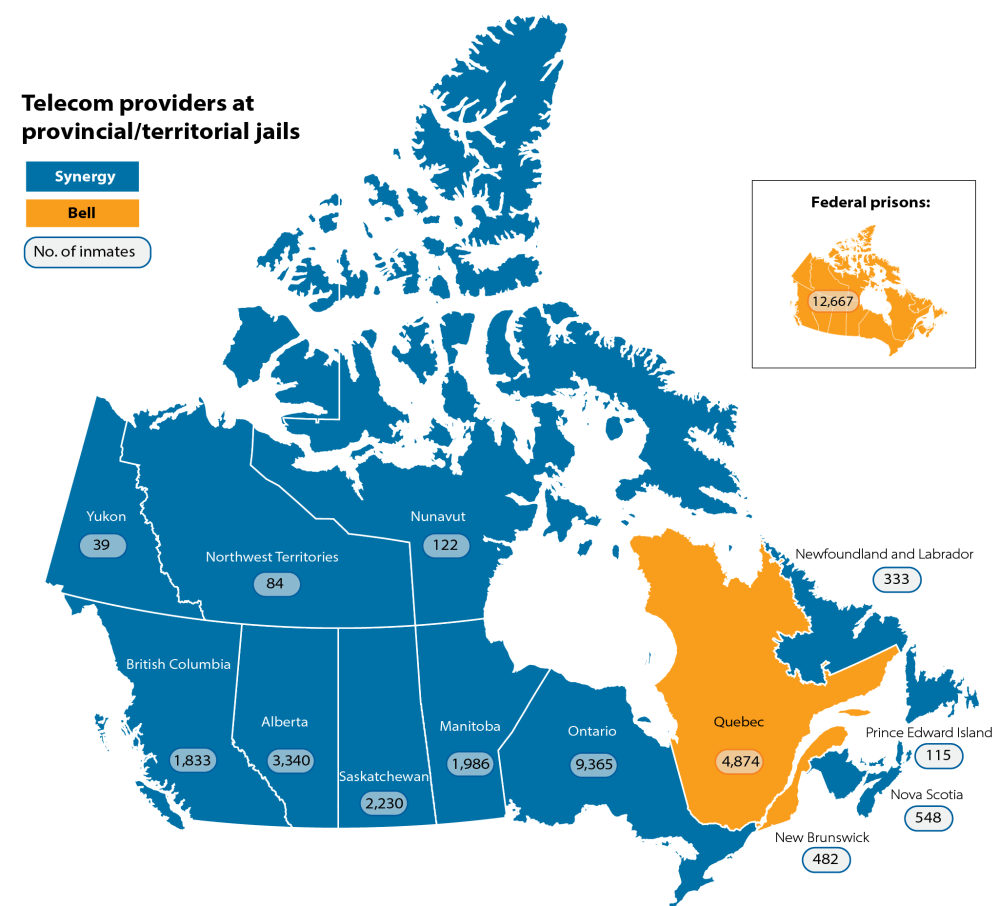

And in Synergy’s case, it’s a market subject to limited regulatory oversight. In roughly 15 years, starting in 2010, Synergy went from holding zero contracts, to working with 12 out of 13 provincial and territorial corrections systems, according to a Free Press analysis. (The sole provincial holdout is Quebec, which uses Bell, as does the federal corrections system.)

Source: Free Press analysis; Statistics Canada figures reflecting the number of people in custody in each province and territory in 2023-24, as of a point-in-time count. (The count for the federal correctional system is from 2022-23, which is the latest data available). (Graphic by Julia-Simone Rutgers)

In jail, the cost of inmates’ phone calls and messages is typically borne by their family members, and often, by women: mothers, sisters, partners. And with Indigenous people making up nearly 80 per cent of admissions into Manitoba’s jails, it’s largely Indigenous women, who already experience high poverty rates, fronting the price of staying connected.

On a given day, Synergy is the source of telephone communication for around 20,500 people incarcerated in provincial and territorial jails.

It represents an astounding market share: 80 per cent of all provincial and territorial inmates, considering 2023-24 figures, with Bell taking the remaining slice.

In addition to being the sole bidder for the most recent RFPs in Manitoba, P.E.I., and B.C., recent contracts Synergy has signed in Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and New Brunswick were sole-sourced, without the veneer of a competitive process.

Before Synergy, a patchwork of companies held these contracts, including WiMacTel, NorthwesTel, and in Manitoba, Bell MTS, according to the Free Press analysis.

Keldon Bester, executive director of the think tank, Canadian Anti-Monopoly Project, said in an interview that while Synergy’s offerings may work well for the Manitoba government now, the lack of competition means the province risks finding themselves in a state of dependency, where they’ll have limited options should they run into issues down the line.

“It’s good until it isn’t, right? Who’s in control?” Bester said.

The details of Manitoba’s contract with Synergy are difficult to parse.

For one, Synergy is a private company, and one which has repeatedly side-stepped questions from Canadian media. For this story, Tanja Sieme, a marketing manager for Synergy’s parent company, said they cannot comment due to the confidentiality of their contracts with correctional services. Any questions, she added, should be directed to the relevant government.

Manitoba government spokespeople did not answer most of the questions posed by the Free Press, including basic queries such as the start and end date of Synergy’s current contract, and nor did they respond to a request to interview a corrections official directly.

A government spokesperson, who asked for anonymity, directed a reporter to submit access-to-information requests for information on the contract.

The Free Press filed several access requests for this story, beginning in July, and only received a single file by publication time, despite a 45-day legislative timeline. (The contents of that 11-page document are entirely redacted, except for the title, date and a single bullet point).

But here’s what can be learned from business registrations, press releases and contract documents: Synergy was founded three decades ago in San Antonio, Texas. It expanded under the leadership of John Crawford, a longtime loan officer, and Charles Slaughter III, a one-time director of the Texas Payphone Association. By 2022, it had 27 employees and generated US$20 million in sales over the previous three years.

Synergy’s nondescript mailing address location in an upscale Toronto neighbourhood.

In Canada, Synergy is registered to a split-level home in an affluent Edmonton suburb. Its mailing address is a rented mailbox in an upscale Toronto neighbourhood. In the U.S., what Synergy calls its “Corporate Head Office” appears to be located inside a single-storey Christian day care on the outskirts of San Antonio.

Two years ago, Synergy’s ownership became more complex when it was acquired by Telio Group, a German prison telecom company that serves more than 400,000 inmates across multiple continents. Telio is owned by Charterhouse Capital Partners, a British private equity firm, with roughly $8.2 billion under management, located in a glitzy office building a short walk from the manicured grounds of Buckingham Palace.

A document obtained through a public records request to the Teachers’ Retirement System of Louisiana gives some sense of Charterhouse’s goals, saying the firm targets “resilient, counter-cyclical, cash generative businesses operating in niche and fragmented markets” for acquisition.

The constellation of companies involved in Manitoba’s contract with Synergy doesn’t stop there: the technology Synergy uses to provide phone and tablet services is not its own. Instead, it’s provided by a subsidiary of Global Tel Link, now rebranded as ViaPath Technologies, which is one of the largest providers of prison telecom services in the U.S.

For its part, ViaPath calls Synergy its “in-country partner” in Canada. (In the U.S., according to an FCC filing, the subsidiary receives customers’ payments and then provides Synergy with a cut).

ViaPath is not without its controversies in the U.S., including several years ago, when a lawsuit over its practice of taking customers’ deposits from their accounts led to a US$67-million settlement, or in 2020, when it uploaded unencrypted personal data of roughly 650,000 customers — including Social Security numbers, medical requests and messages — online, some of which filtered onto the dark web, according to a U.S. Federal Trade Commission complaint.

Synergy’s expansion into Canada came around the time the FCC began, in 2013, setting caps on the calling rates and additional fees that prison telecom companies like Synergy could charge in the U.S.

Bianca Tylek, the executive director of Worth Rises, a New York City-based non-profit that advocates against the commercialization of prisons, believes increasingly tight regulation of the industry in the U.S. likely played a role in Synergy’s push into Canada.

In the U.S., the prison telecom industry is a duopoly: with ViaPath, which was previously known as Global Tel Link or GTL, and another firm, Securus Technologies, cornering roughly 90 per cent of the market. Tylek said Securus has been struggling under an enormous debt load, while GTL is not in a similarly dire financial position.

“I wonder if the reason that GTL was able to do something that Securus was not able to do, is because it has a global footprint that is less affected by — well, that is not affected by the increase in U.S. regulation,” she said.

For its part, Manitoba opted to replace Bell MTS in 2016 because its equipment became “outdated and no longer serviceable,” a memo written by a corrections official outlines. In its place, Synergy’s Internet-based phone service was chosen, with “kiosks” installed in the province’s jails, where members of the public could deposit money into inmates’ accounts, the memo says.

Yet in an era of “elbows-up” patriotism, as Premier Wab Kinew’s government announced it was ending its contract with a Texan company responsible for selling provincial park passes — in favour of a Canadian replacement — its contract with Synergy has escaped scrutiny.

In Manitoba jails, a single, 15-minute pre-paid call currently costs $3, not including tax, while collect calls are $4.30, according to a government web page. Though recently, the province has added an additional option: inmates and their families can purchase bundles of pre-paid calls at a lower cost. A package of fifteen pre-paid calls costs $19.05.

But that is not the total price.

Synergy also charges a $5 fee, for an unspecified purpose, as well as a 14 per cent “convenience fee” on these bundles. It is unclear how the two fees differ.

At this rate, it would cost around $165 a month if an inmate made three paid calls per day, before tax.

Unsentenced inmates are allowed three free calls daily, as are incarcerated youth, while calls to lawyers and certain organizations, like the Manitoba Ombudsman, are also free.

Pre-paid packages expire after 30 days.

“Manitoba’s deposit fee of $5, plus a 14 per cent ‘convenience fee’… (is) in excess of what the FCC decided was appropriate 10 years ago.”

Two U.S. advocates blasted the additional fees Synergy is charging in Manitoba.

Wanda Bertram, a spokesperson with the Prison Policy Initiative, a Massachusetts-based non-profit that researches the prison telecom industry, noted that in 2015, the FCC capped fees for making a credit card deposit towards an inmate’s account at US$3.

“Manitoba’s deposit fee of $5, plus a 14 per cent ‘convenience fee’… (is) in excess of what the FCC decided was appropriate 10 years ago,” Bertram said.

Meanwhile, Bianca Tylek, with Worth Rises, said Manitoba’s base rate for pre-paid packages is high, though not unheard of. But, like Bertram, she sharply criticized the additional fees, calling them “outrageous.”

“It’s so much,” she added.

Under pressure from organizations like Worth Rises, six states, including California, Massachusetts and Minnesota, now offer free calls in their prisons. (In 2018, an inspection report of Yukon’s only jail recommended that calls be made free, but this was not implemented.)

In Canada, certain phone rates inside federal prisons are regulated by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), which is the equivalent of the FCC in the U.S. Bell, which operates the phone system inside federal prisons, must submit these rates to the commission for approval, based on whether the charges are considered “just and reasonable.”

In comparison, none of Synergy’s rates are subject to the CRTC’s scrutiny. Unlike Bell, Synergy is not considered a “Canadian carrier” under the Telecommunications Act and its rates are therefore not subject to the commission’s approval.

Yet Bell has still drawn criticism over its pricing. It is the subject of a proposed class-action lawsuit over its rates in Ontario’s jails, prior to Synergy taking over in 2021, which, the litigation has noted, resulted in lower costs to inmates under Synergy.

“The Crown provided a captive population in need of phone services, while Bell charged excessive rates and funnelled Commissions to the Crown,” reads an amended statement of claim, which refers to these commissions as an “unlawful and unconstitutional tax” on inmates.

The CRTC may be tightening its approach.

Though not directly involved in the Bell lawsuit, the commission was drawn in to answer a procedural question, and in a decision last year, expressed “broader concerns” about rates being charged to inmates in jails and prisons across Canada, saying it would assess whether further action, “including potential regulatory intervention,” was required.

Earlier this week, the CRTC sent a letter to Bell and Synergy, as well as a few other companies, and each correctional jurisdiction. It asked each company for a record of their correctional revenues since 2020 and contained several specific requests of Synergy, including for details of its full ownership structure.

Tablets, which are available at the Headingley Correctional Centre, contain access to certain approved songs and movies, as well as a messaging platform. These paid services cost 13 cents per minute for inmates to use. For their family members, it costs 50 cents to send a single message, with a limit of around 250 words.

For the people actually paying the fees, Synergy feels “predatory,” said Tammy Wolfe, a member of Norway House Cree Nation who ensured her brother was able to make phone calls while he was incarcerated in Manitoba jails over several years.

“It’s expensive for the calls, it’s expensive to put money on their books,” she said. “It feels predatory.”

Wolfe, a PhD candidate in Indigenous Studies at the University of Manitoba, reconnected with her brother in 2017, after they were separated as young children and both put into the child-welfare system following their mother’s death. Her brother struggled in his life — not just with his childhood, but with the systemic issues that came with being apprehended into child welfare, Wolfe said.

Starting in 2020, he was in and out of the Winnipeg Remand Centre and other provincial jails for about four years. He died in March, at age 25, just weeks after his most recent release.

To stay in touch, Wolfe bought packages of pre-paid calls from Synergy. But if her brother didn’t use them by month’s end, they’d expire, making it impossible to have a reserve in case of emergencies.

“It’s almost like they know that they can charge whatever they want, because there’s that connection with the people inside to their loved ones on the outside — that’s their only means of communicating. So of course, you’re going to pay,” she said.

Wolfe said the system is harming Indigenous families like hers and it will continue to extract money from them, unless something changes. And she points out, with poverty contributing to the disproportionate number of Indigenous people in Manitoba’s jails, it’s antithetical to then force them to require money to communicate with their family members.

“Do you think that person is going to be rehabilitated?”

In-person visits are impossible for many inmates, particularly if their families live in remote First Nations communities, said Merissa Daborn, an assistant professor of Indigenous Studies at the University of Manitoba, who has researched Synergy’s operations in the province.

As a result, Indigenous communities end up relying on phone calls and messaging to stay connected, she explained.

“It’s almost like they know that they can charge whatever they want.”

Daborn said she’d like to see more transparency from Manitoba Justice on the details of their contract with Synergy, including whether their privacy policies are compliant with Canadian laws. (Manitoba Justice, which is responsible for corrections, refused a Free Press access request for a copy of the province’s contract with Synergy, saying the department does not have a copy).

Research shows inmates who maintain connections with loved ones while incarcerated are less likely to re-offend, Daborn said, and Synergy’s fees run counter to the province’s belief that rehabilitation is an important aspect of incarceration.

“My views are that prisoners should have access to open visits, open communications, that they shouldn’t be paying for these services while they’re incarcerated, and that also that there shouldn’t be surveillance of those communications while they’re incarcerated, either,” Daborn said, before pausing.

“That’s not going to be a popular view.”

A portion of Synergy’s profits are routed back to the province through what is known in the prison telecom industry as a “site commission.”

In the U.S., these commissions are often around 50 per cent of revenue, though typically additional fees are excluded from that calculation.

It’s unclear what cut Manitoba is taking. A provincial spokesperson would not say, and a section titled “Commission Rate” in a copy of the 2016 contract is redacted.

According to the 2019 superintendents’ meeting minutes, this commission was required to be put towards inmates’ welfare and, specifically, could be used to pay for “Indigenous initiatives” or other jail programming, as well as modular furniture, exercise equipment and clothing for inmates to wear upon their release.

A provincial spokesperson confirmed this week that Synergy’s commissions can still be used to fund Indigenous programming.

In other words, families of inmates are subsidizing services that are the responsibility of the province. More specifically, it means Indigenous families may be paying for Indigenous cultural programming. Daborn, the Indigenous Studies professor, said this dynamic would be “unconscionable,” given that overincarceration of Indigenous people has been linked to “systemic racism, the ongoing colonization of Indigenous territories and legacies of colonial policies in Canada.”

Tylek, with Worth Rises, said what is deemed inmate welfare is often “pretty loose,” adding “the reality is, we’ve seen them justify everything from painting the walls, like maintenance of the facility.” And, she said, if the inmates’ welfare is the goal, “then there’s nothing that could better do that than providing cost-effective or free communication, right?”

To Bester, with the Canadian Anti-Monopoly Project, the commission model is not in line with competitive contracting.

“They’re basically agreeing to a conflict (of interest) and ensuring substandard service and creating the incentive actually to push prices higher because, again, you have this captive audience,” Bester said, noting that, outside of jails, telecommunication delivery has become cheaper over the last two decades.

And as for issues that can arise without a competitive bidding process, “the usual monopoly things happen: prices go up, quality goes down, innovation goes down,” Bester said.

Increasingly, Synergy is gobbling up new markets.

Synergy now contracts with most provinces and territories, including Manitoba, to provide money-transfer services, which are used to top up inmates’ trust accounts to buy items like deodorant, nail clippers and soap. These deposits are, again, subject to high fees, though they are not specified on the government’s web page.

And the company is also making a strong push into tablets.

In the U.S., when regulations began limiting prison phone rates, the industry sought out other profitable avenues, explained Bertram, with the Prison Policy Initiative.

This included mail scanning, video visitation and tablets, which can be used to access certain forms of media like movies and songs, as well as a messaging platform — each with a cost. As companies “aggressively” marketed these services, one of their strategies was to offer tablet hardware to their clients for free, she said, as took place in Manitoba.

A New Hampshire prison correctional officer returns a GTL tablet to a charging cabinet.

Synergy uses technology owned by GTL, now called ViaPath, to deliver its services in Canada.

In 2019, tablet use in Manitoba’s jails was slated to cost 10 cents per minute. It’s now 13 cents.

The fees start racking up whenever an inmate logs into the tablet’s entertainment section; starts composing a message; or re-reads a message they’ve already received. And with family members paying 50 cents to send a single message — with a limit of roughly 250 words — it means there’s a cost to both sending and receiving correspondence.

This 50-cent charge for family members’ messages is on par with the highest rate charged by any U.S. state prison system, according to a 2023 analysis by the Prison Policy Initiative.

As for the 13-cent-per-minute tablet rate, Bertram said this is far higher than rates she’s seen in the U.S. She added that per-minute pricing is “especially insidious” because it disadvantages those with intellectual disabilities or limited technology skills.

“If you struggle with reading, if you have poor eyesight, (or) if for any other reason, you struggle with using a tablet, you’re going to pay more,” she said.

“If you struggle with reading, if you have poor eyesight, (or) if for any other reason, you struggle with using a tablet, you’re going to pay more.”

In public, Synergy focuses on the connective power of tablets, saying in one press release the devices “humanize the correctional experience.”

But in a 2022 bid proposal to one Nebraska county, the company emphasized something different, saying that tablets — and the details of inmates’ messages — provide powerful new investigatory techniques, such as having access to photos of people inmates are communicating with.

For its part, Manitoba points out there are free resources on the tablets, including: “approved photos, facility forms, resource information, custody release planning resource document, cultural content and facility inmate handbooks.”

But one man, after being released from the Winnipeg Remand Centre, put it differently when asked what’s available for free.

“Nothing. You need money.”

marsha.mcleod@freepress.mb.ca

malak.abas@freepress.mb.ca

Marsha McLeod

Investigative reporter

Signal

Marsha is an investigative reporter. She joined the Free Press in 2023.

Malak Abas is a city reporter at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg's North End, she led the campus paper at the University of Manitoba before joining the Free Press in 2020.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, October 3, 2025 9:34 AM CDT: Corrects image cutline

Updated on Friday, October 3, 2025 9:39 AM CDT: Removes headers

Updated on Friday, October 3, 2025 12:45 PM CDT: Minor copy editing change

Updated on Monday, December 1, 2025 12:57 PM CST: Adds graphic cedit