Poverty-stricken Manitoba First Nation strikes gold Historic mining agreement offers hope for northern Indigenous community, declining town of Lynn Lake

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/06/2023 (892 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

MARCEL COLOMB FIRST NATION — Marcel Colomb may currently be one of the poorest First Nations in Canada, but it is literally sitting on a gold mine.

On Tuesday — after a feast with most of the approximately 100 members of the northern Manitoba community (and many of its canine population) in attendance — Chief Christopher Colomb signed a historic revenue-sharing agreement with Alamos Gold Inc. chief executive officer and president John McCluskey.

The impact benefit agreement is the first of its kind in Manitoba between a mining company and First Nation.

In chilly 6 C temperatures, residents of the tiny reserve about 20 kilometres from the town of Lynn Lake (an 11-hour drive northwest of Winnipeg) gathered for an event that could be transformational for a community whose members faced extreme hardship for decades, before being allowed to establish their own First Nation in 1999.

MARTIN CASH / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Christopher Colomb (left) chief of Marcel Colomb First Nation and John McCluskey CEO of Alamos Gold after signing an impact benefit agreement for the community to participate in the $500 million development of open pit gold mines near the reserve outside Lynn Lake, Man.

It’s been more than 30 years since any economic activity has taken place in this corner of the province at the end of Provincial Highway 391 — when mines in both Lynn Lake and Leaf Rapids closed for good.

Since then, the population of Lynn Lake has plummeted to about 900, from some 5,000.

There is no scheduled air service to Lynn Lake. More than half of its homes are boarded up and many of the rest are in poor repair. At one time, Colomb said, you could buy a house in town for $1.

The town has a grim, colourless look. There are few cars in the hospital parking lot. The former movie theatre looks as if it hasn’t been open for decades.

A newish-looking school bus sits alone on the side of a road, blocks from the school. Colomb said officials couldn’t find anyone with the required licence to drive it.

Although MCFN was awarded its own reserve in 1999, it took another 10 years before any homes were built. However, many have since been erected, some yet to be occupied. A new water treatment facility on the reserve works so well, for a time it was trucking water into Lynn Lake when the town was faced with boil-water advisories.

FREE PRESS ARCHIVES It’s been more than 30 years since any economic activity has taken place in this corner of the province at the end of Provincial Highway 391 — when mines in both Lynn Lake and Leaf Rapids closed for good.

Years before that, community members — many of them trappers originally from Mathias Colomb in Pukatawagan (about 100 km south) with registered trap lines in the Lynn Lake area — lived in a tent village behind the town hospital.

“We weren’t allowed to go to town. We had to be escorted by the RCMP. We had no money. Sometimes, we had to live off the dump,” said Andrew Colomb, MCFN’s first chief (and the current chief’s uncle).

“Our children had to go to residential schools and they would come home at Christmas to plastic tents in minus 40-degree temperatures.”

The Lynn Lake town council recently erected a memorial at the site.

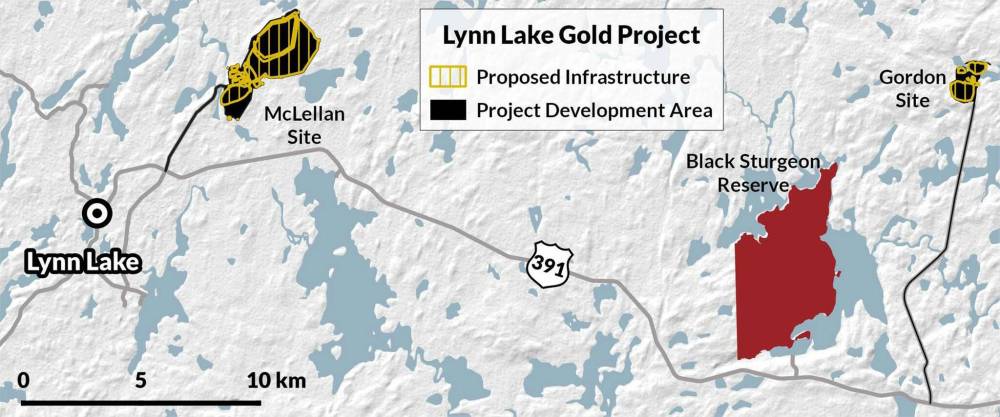

Alamos Gold, which acquired the mining property in 2016, has received most of the important permits it needs to build two open-pit gold mines around the reserve and nearby town. It is in the process of updating a feasibility study to acknowledge an increase in the amount of gold it believes it will be able to extract, now up to 170,000 ounces per year.

The agreement includes commitments for jobs and training, heightened environmental protections and revenue sharing — including a milestone payment to the band when construction begins.

SUPPLIED Lynn Lake Gold Project.

“There has not been work here since the old mine closed, especially for us Natives,” Chief Christopher Colomb said. “We don’t get the jobs. We have been on welfare for quite some time. It’s time everyone gets off it and comes to work.”

A number of other First Nation communities in the region — including Mathias Colomb, Lac Brochet, Brochet, South Indian Lake and Granville Lake — are also expected to benefit from the Alamos development.

“Working with Alamos will better our future leaders and our grand-kids,” Colomb said. “We won’t be here for all the spoils. This is to prepare for future generations.”

Chris Roine, the band’s legal representative for the mine negotiations, said the first milestone payment, following the agreement-signing, will wipe out the last of the MCFN’s debt.

“We don’t get the jobs. We have been on welfare for quite some time. It’s time everyone gets off it and comes to work.”–Chief Christopher Colomb

The plan is to establish a legacy trust fund with the Alamos revenue.

“If we follow Alamos’s projections, in 20 years, the annual interest from the trust fund will be more than the band receives from Indigenous Services Canada,” said Roine, former director general of Crown-Indigenous relations.

The name chosen for the trust fund is the Cree word for “our grandchildren.”

McCluskey said the final analysis is not complete but the Toronto-based company will likely need to invest “north of $500 million” to develop the operation.

The two open-pit mines and a mill that will be able to handle 7,500 tonnes of ore per day will take a couple of years to build. It will need to employ about 400 people when it is up and running, and it’s estimated it will be able to operate for roughly 20 years.

“This (signing) is an important first step; both sides worked hard to get to the agreement. The benefits to the community are pretty strong. They are the kind of things that can really help with economic revival, especially since there has been no significant investment in this part of the province for decades,” McCluskey said.

MARTIN CASH / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Alamos currently has three working gold mines (two in Ontario, one in Mexico) and has been heralded as both a financially successful operator and strong environmental steward, with good community relations wherever it operates.

Even though construction may not start for another two years, the company has had about 20 employees in Lynn Lake for some time.

Employment training co-ordinator Holly Martin (an Indigenous woman from the area and a former underground mine supervisor with Vale) said work is already underway to identify people in the region to fill the jobs, including about 150 drivers.

“We’re building a data base of what skills people would like to receive and then measure that versus the skills we are going to need,” she said.

Christian Sinclair, former chief of Opaskwayak Cree Nation and economic development specialist who cut his teeth on projects with the Cree of James Bay, has been instrumental in organizing MCFN negotiations with Alamos.

In addition, Sinclair has already helped MCFN set up joint ventures with a Saskatoon-based construction company and a B.C.-based work camp caterer.

Those joint ventures will have to bid on contracts, but the framework will make it possible for sustainable employment opportunities for MCFN for some time, Sinclair said.

Meantime, concern for the social and environmental well-being of First Nation communities remains at the fore, he said. “Environmental protections have always been the No. 1 priority, weighted heavily against any financial benefits.”

martin.cash@freepress.mb.ca