From humble Red River roots to pre-eminent Manitoba premier In Manitoba's early days, larger-than-life Métis politician John Norquay fought for a better deal for the province in federation

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/08/2023 (846 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Manitoba could reach a significant milestone following the Oct. 3 provincial election should the NDP and its leader Wab Kinew, who is Anishinaabe, emerge victorious. It would be the first time in its 153-year history that the province elects a First Nations premier.

Kinew, though, would not be Manitoba’s first Indigenous premier. That distinction belongs to former Métis premier John Norquay, who held office between 1878 and 1887 and who had a profound impact on the province. This is his story.

When John Norquay returned to Manitoba after one of his many working trips to Ottawa, he rarely came home empty-handed.

Norquay, Manitoba’s premier from 1878-87, was relentless in his pursuit of “better terms” for his fledgling province, which was still battling at the time for equal treatment within Canada.

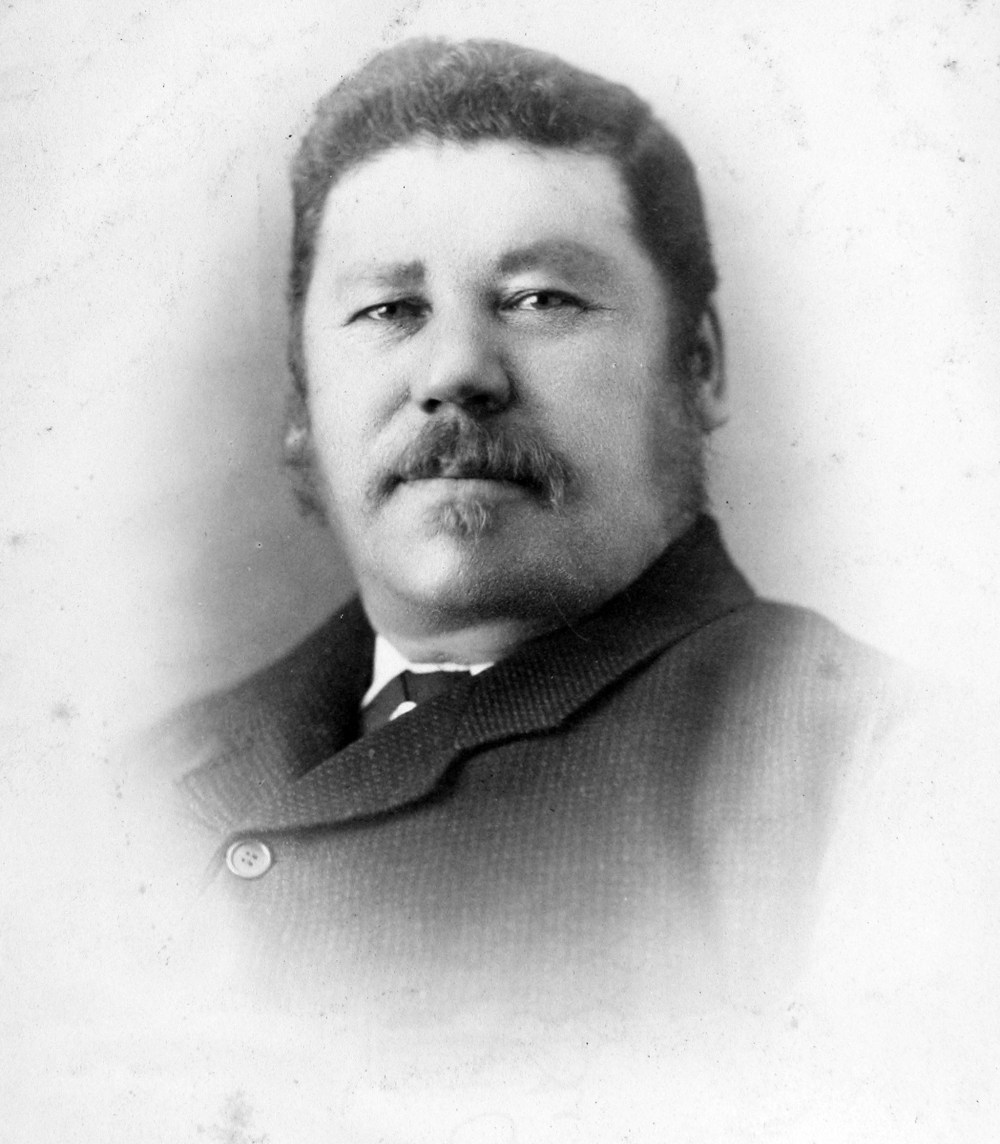

MCCORD STEWART MUSEUM John Norquay was Manitoba’s premier from 1878-87.

Manitoba, barely a decade old, required land, money, railway lines and infrastructure to compete in the new world it found itself in and to gain equal footing with the more developed provinces to the east.

It was the job of any Manitoba premier to lobby the federal government aggressively for those resources and to improve the province’s standing within the federation. Norquay did that as well, or better, than any first minister of his time.

“Norquay really was the first major western Canadian regionalist,” said Gerald Friesen, a retired history professor from the University of Manitoba who is putting the finishing touches on a biography of Norquay (more on that below).

“I think at the time he was regarded as a very successful, very attractive politician and an effective defender of Prairie and Manitoba rights.”

John Norquay was Manitoba’s first premier born and raised in his home province. He was also the province’s first Indigenous premier after Manitoba joined Canada in 1870.

Norquay was an English-speaking Métis of Orkney-Scottish and First Nations descent (commonly and less pejoratively known in 19th-century Canada as an English “half-breed”).

He spoke multiple languages — English, French, Cree and other Indigenous languages — and had deep roots in his community. He benefited from a formal education, including a scholarship he received as a teen, something most people who grew up in the Red River Settlement at the time did not have.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA Norquay spoke multiple languages — English, French, Cree and other Indigenous languages — and had deep roots in his community.

Norquay was articulate, intelligent and had a unique perspective on how to bridge the isolated world where he grew up with the new nation-state of Canada. His gregarious and warm-hearted nature made him a suitable and valuable candidate for public life.

He was as comfortable waxing eloquently in Manitoba’s legislative assembly or bartering with top officials in Ottawa as he was hunting wild fowl or dancing the Red River jig (it was said Norquay always took two pairs of moccasins to the dance with his wife Elizabeth Norquay because he would always wear out the first pair).

He also had a wry sense of humour. When Conservative prime minister John A. Macdonald wrote to Norquay in October 1881 to complain Manitoba’s rules for admitting out-of-province lawyers were too restrictive, Norquay replied he would change them, but commented, “I may add that although we don’t profess to have a higher standard of education than in Toronto or Quebec none of those educated with us spell Christ with a K as was the case with some of those applying for admission.”

The former teacher was a giant of a man — standing six feet tall and weighing some 300 pounds — who became an effective and crafty politician. He made his mark not only in provincial politics, but also on the national stage, particularly through his legendary battles with John A. Macdonald.

He was lauded for his conciliatory approach to politics and regarded affectionately for his fair-mindedness and generosity, even among many of his political opponents. Norquay’s integrity and knack for working across racial, linguistic and religious lines earned him the nickname “Honest John.”

Provincial trailblazer had deep roots

Key dates in the life of John Norquay:

• Born May 8, 1841 near St. Andrews, Manitoba.

• Descendant of Hudson’s Bay Company servants who worked on northern rivers and shores of Hudson Bay in 18th century. Norquay’s maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Vincent, was the daughter of an HBC officer and an Indigenous woman.

• Norquay’s mother died in 1843 and his father died in 1849. Norquay was subsequently raised by his paternal grandmother, Mrs. James Spence.

Key dates in the life of John Norquay:

• Born May 8, 1841 near St. Andrews, Manitoba.

• Descendant of Hudson’s Bay Company servants who worked on northern rivers and shores of Hudson Bay in 18th century. Norquay’s maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Vincent, was the daughter of an HBC officer and an Indigenous woman.

• Norquay’s mother died in 1843 and his father died in 1849. Norquay was subsequently raised by his paternal grandmother, Mrs. James Spence.

• Attended Anglican St. John’s Collegiate School where he received a scholarship in 1854 from Archbishop David Anderson.

• Worked as a teacher in late 1850s, including at St. James’ Church school.

• Married Elizabeth Setter, also of mixed ancestry, in 1862. Couple moved to High Bluff near Portage la Prairie in mid-1860s to farm.

• Did not participate directly in 1869-70 Red River Resistance, but did attend some related meetings. Signed his cousin John Lazarus Norquay’s election certificate when latter was elected to Louis Riel’s second provisional government in early 1870.

• Elected to Manitoba’s first legislative assembly by acclamation Dec. 27, 1870, in the High Bluff constituency.

• From 1874 to early 1880s, Norquays lived on a small farm in St. Andrews district north of Winnipeg. Won St. Andrews district seat, home to many English-speaking Métis, in legislature in 1874 and held the riding until his death.

• Appointed to cabinet in 1871 by Lt.-Gov. Adams Archibald, served as minister of public works and agriculture. (Lieutenant-governors chose cabinet members in Manitoba between 1870 and 1874).

• Ran federally in Marquette but was defeated.

• Served in cabinet under various governments and briefly as opposition leader between 1871 and 1878.

• Succeeded Robert Davis as premier in November 1878. Won an election as premier later that month with a majority of 14 to 17 French-speaking and English-speaking members in 24-seat legislature.

• Won four consecutive elections as premier.

• Became a Conservative premier by mid-1880s when political parties were introduced into Manitoba politics.

• Convinced federal government to expand Manitoba’s boundaries in 1881 and gained “better terms” from Ottawa throughout 1880s, including larger subsidies.

• Attended the first premiers’ conference held in Canada in 1887, the “Interprovincial Conference” in Quebec City, as the only non-Liberal premier.

• Battled with prime minster John A. Macdonald over railway politics and Canadian Pacific Railway’s monopoly clause for most of 1880s. Resulted in his ultimate defeat in December 1887 when he stepped down as premier.

• Died in 1889 in his Winnipeg home of a twisted bowel. Was still an MLA and leader of the opposition at the time.

• Places named after Norquay: Norquay School (Winnipeg), Norquay Building (401 York Ave.), Norquay Community Centre (Winnipeg), the town of Norquay (Saskatchewan), Mount Norquay, Banff National Park (Alberta), John Norquay Elementary School (Vancouver, B.C.).

Norquay was a Conservative politician in federal circles but resisted the introduction of party politics in Manitoba as long as he could. Manitoba governments in the early years were made up of loose coalitions between linguistic and religious groups, old settlers, newcomers and others.

Norquay believed a provincial government with no party ties could more effectively negotiate with the federal government. It was an admirable goal, but it didn’t last. By the mid-1880s, party politics were firmly established in Manitoba, as they were elsewhere in Canada, and the Norquay government became a Conservative one.

Norquay played no active role in the Red River Resistance of 1869-70, where the Métis, led by Louis Riel, took up arms to force negotiations with the federal government prior to joining Canada. His entry into local politics came several months later when he won a seat in Manitoba’s first legislative assembly in December 1870. His rise to cabinet was quick (he was leader of the opposition, beginning in 1875, for a short spell) and his ascension to the premier’s office took only eight years.

Norquay became widely regarded as a respected statesman. The Manitoba Free Press noted in 1875 that “a greater tribute of respect could not be paid to the English Half-breeds in the Province than has been, by the election of Mr. Norquay as leader, by an Opposition composed chiefly of newcomers.”

Norquay, a farmer and father of a large family, became premier in 1878. For the next nine years, he presided over one of the province’s most important periods of development and fought relentlessly to strengthen provincial rights within Confederation.

“(Norquay was) somebody who had a distinctive vision of Canadian provinces within the federal system, where provinces were equal to the federal government within their spheres of power,” said Friesen. “That’s become a theme in recent years in Canadian politics, but it wasn’t a theme 30 and 40 and 50 years ago.”

And so went Norquay to Ottawa, year after year, with his small entourage of Manitoba delegates, meeting with Macdonald (who was both an ally and a foe of Norquay at different times during his premiership) on behalf of the community where his ancestors lived long before it became Canada. He stubbornly pursued equal treatment for Manitoba and was unwavering in his demands that Ottawa provide it with greater subsidies.

“(Norquay was) somebody who had a distinctive vision of Canadian provinces within the federal system, where provinces were equal to the federal government within their spheres of power.”–Author Gerald Friesen

Under the terms of Manitoba’s entry into Canada in 1870, the province did not own most of its public lands, nor have control over its natural resources, as other provinces did. Norquay was adamant that Manitoba be compensated for that.

His perseverance paid off. The premier convinced Macdonald and his cabinet to substantially increase subsidies to the province in lieu of Crown lands.

He fought for and was granted lands to drain for agricultural purposes and given the resources to do it — a critical factor in building the province’s economic base. Norquay obtained real estate for schools, negotiated a land grant for the University of Manitoba and pressed the federal government on its constitutional obligation to fund the construction of public buildings in the new province, which Ottawa ultimately did.

One of his greatest achievements: Norquay convinced the federal government to expand Manitoba’s boundaries in 1881 beyond its original “postage stamp” size (they were further expanded in 1912). The expansion was a major accomplishment, and an important one economically, for which Norquay was celebrated at the time.

A banquet attended by local dignitaries was organized at the Queen’s Hotel in Winnipeg on March 29, 1881, “in recognition of his services in securing the extension of the Provincial Boundaries,” a notice in the Manitoba Free Press read.

“Our province is now equal in size to Ontario with resources as great and affording facilities for settlement superior to that of any other province of Confederation.”–John Norquay

Still, Norquay recognized that, even with its expanded boundaries (which grew to about the size of Ontario at the time) and increased subsidies, Manitoba was not on equal footing with other provinces because it still did not own most of its public lands nor have control of its natural resources. He vowed to continue to fight for “better terms” with Ottawa.

“Our province is now equal in size to Ontario with resources as great and affording facilities for settlement superior to that of any other province of Confederation,” Norquay said during a speech in the legislature in May 1882. “Yet there is indeed a very hard struggle before us with the federal government to induce them to give to us the control of our public domain and thereby place us in the same position as the other provinces of Confederation.”

Norquay’s time in office was not without controversy.

He was accused of benefiting financially from land he owned in the Selkirk area, which was ultimately purchased by the provincial government to build an asylum, and for profiting from a coal company, of which he held an interest, that did business with the Manitoba government.

So embroiled was the premier in allegations of corruption that he called a royal commission to investigate claims he misused public funds. He was ultimately cleared of wrongdoing.

“There is indeed a very hard struggle before us with the federal government to induce them to give to us the control of our public domain and thereby place us in the same position as the other provinces of Confederation.”–John Norquay

Norquay’s most daunting political battles, though, were almost always linked to railway policy.

The federal government, under Macdonald, signed a monopoly clause with the Canadian Pacific Railway to build a transcontinental railroad through Manitoba to the Pacific Ocean as part of its so-called National Policy. While Norquay did gain some concessions from Ottawa on railway location in the province, his attempts to interfere with the railway monopoly, for the benefit of Manitoba farmers and traders, enraged Ottawa and CPR brass.

The Manitoba premier sought lower freight tariffs by introducing competing branch lines within the province, including a plan to build a government-funded railway — the Red River Valley Railway — to the U.S. border. Norquay believed Manitoba had the constitutional authority to do so, Macdonald did not. And so the battle lines were drawn.

Macdonald and CPR president George Stephen waged a fierce battle against Norquay, first by disallowing provincial railway legislation (federal disallowance of provincial bills occurred regularly in the early years of Confederation) and by preventing the province from raising the money needed to fund its proposed branch lines.

In early 1887, when the CPR got word the province was planning to build a competing railway line to the U.S. border, Stephen fired off a scathing telegram to Norquay, accusing the people of Winnipeg of treating the CPR as a “public enemy” and threatening to move the railway’s shops out of the city.

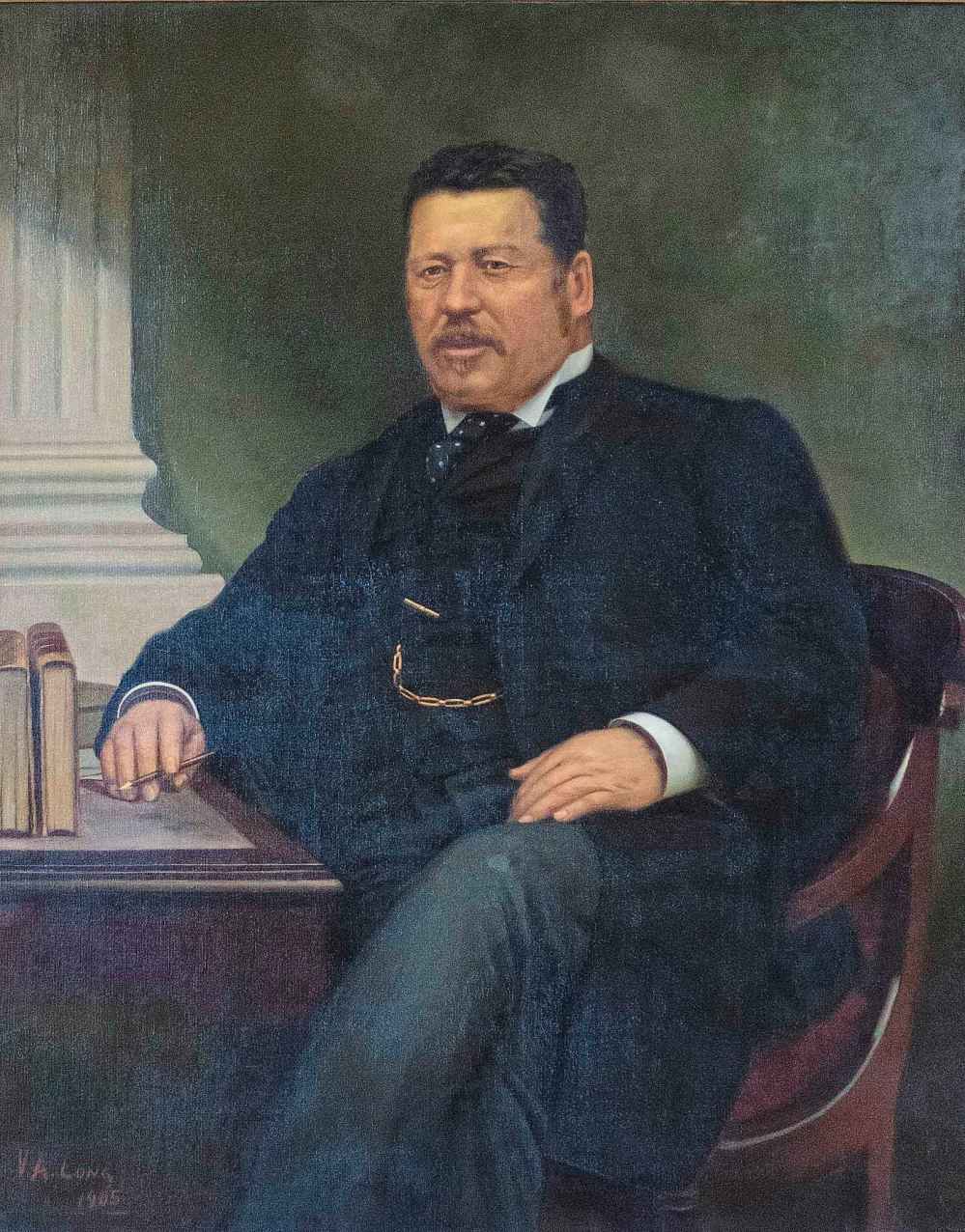

MIKE THIESSEN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS A portrait of Hon. John Norquay, hangs in the Legislative Building.

“Pray do not be mistaken,” wrote Stephen in the telegram, the contents of which were published in the Free Press. “This is not an idle threat, it is a fixed purpose, taken after full consideration.”

Stephen never acted on the threats, but his rhetoric and Macdonald’s repeated disallowance of provincial railway charters fuelled a backlash in Manitoba and incited talk among some of separating from Canada. It was an unsettling time in a province not always convinced of the benefits of its membership in the federation.

Norquay, always the diplomat and a steadfast defender of Confederation, discouraged the idea of secession (although he played it up at times for political leverage). Nevertheless, his bitter feud with Macdonald and the CPR over railway politics would ultimately spell the end of his premiership.

In debates in the legislature in the spring of 1887, Norquay said it was important to respect the interests of CPR shareholders and Canadians, who subsidized the construction of the transcontinental railway. But he also argued Manitobans deserved to have competitive freight rates through local branch lines.

“I do say that every effort of mine within the bounds of the constitution shall be adopted to construct independent lines to the south,” Norquay vowed.

In a desperate attempt to secure funding for Manitoba’s railways, and to keep his government solvent, Norquay travelled to Chicago, New York, Toronto and Montreal in late summer and early fall of 1887 in search of financing, but to no avail.

Everywhere he went, he was turned down by financial institutions, often owing to the direct or indirect intervention of Macdonald or Stephen.

Earlier that year, a previously approved $1-million bond from a financing firm in London, England, negotiated by the Manitoba government, was withdrawn after Macdonald used his influence to scuttle the deal. The prime minister was determined to bleed the provincial treasury dry, either to prevent the construction of branch lines, force Norquay out of office — or both.

“(Norquay) resisted the big business powers and met his fate as a result,” said Friesen.

By the end of 1887, the Manitoba government was broke, unable to meet its civil service payroll or pay the bills piling up from the preliminary construction costs of the Red River Valley Railway.

“(Norquay) resisted the big business powers and met his fate as a result.”–Author Gerald Friesen

The provincial government, which relied on Ottawa for most of its funding in those days, was in a financial crisis. Its near-bankruptcy became the impetus for a provincial cabinet revolt, in which Macdonald played a role.

The prime minister not only tightened the screws on the provincial treasury, he spread unsubstantiated rumours about financial impropriety in the premier’s office and tried to pressure lieutenant-governor James Aikins to replace Norquay. His tactics were ruthless but successful.

Norquay still hoped he could survive the political onslaught. In several letters to rural supporters in early December, the premier vowed to soldier on.

“The situation looks bluer than ever it did before” Norquay wrote to one rural supporter, adding he still hoped “to pull through notwithstanding all the bluster of the opposition.”

To another he wrote: “You and the other friends of the government may rest confident that we are prepared to meet any and all charges that may be brought against us. Thanking you and those who loyally stick by the government in giving us your support in trying to bust up the monopoly of the C.P.R.”

“You and the other friends of the government may rest confident that we are prepared to meet any and all charges that may be brought against us.”–John Norquay

But it was too late. As 1887 wound down, Norquay realized resistance was futile. The premier, once an ally of Macdonald, saw no way out but to resign as premier, which he did on Dec. 24, 1887.

He was replaced by fellow cabinet minister David Harrison, who lasted only three weeks in the job after a caucus revolt led to the government’s resignation (ironically, Norquay was elected leader of his caucus again). Liberal leader Thomas Greenway took over as premier in mid-January 1888.

Funds began to flow again into provincial coffers almost immediately after Norquay’s resignation, eliminating any doubt that Ottawa’s efforts to undermine the province’s finances were politically motivated.

It was an inglorious end to an otherwise impressive nine-year reign for Norquay.

He stayed on as an MLA, but his personal financial troubles (which dogged him for most of his political career, as he regularly spent and gave away more money than he earned) forced him to supplement his MLA stipend with other jobs, including as a law clerk and an insurance salesman.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / FREE PRESS FILES John Norquay’s headstone at St. John’s cemetery. He died suddenly at the age of 48.

He met an untimely death in 1889 when he was afflicted by a twisted bowel that ended his life quickly at the age of 48.

Two decades later, reflecting on Manitoba’s pioneering days, The Winnipeg Tribune praised Norquay.

“Mr. Norquay called himself a Conservative, but he was a very liberal-minded man, quite free from cheap partisanship and always ready to ally himself with any men in public life of the province with whom he felt that he could honourably co-operate in the administration of public affairs,” the newspaper wrote.

“He was a patriotic man, a fine speaker, and had a reputation for integrity and square dealing that earned for him the sobriquet ‘Honest John Norquay.’”

The Winnipeg Free Press was less generous in its assessment of Norquay. In 1920, commemorating the province’s 50th anniversary, Free Press editor John W. Dafoe wrote that Norquay’s political demise was caused by his battles with the federal government over railway policies, but also the “very unsatisfactory terms” he negotiated with Ottawa, including his failure to gain control of public lands and natural resources.

“John Norquay was a man of unbounded popularity and of remarkable attainments,” Dafoe wrote. “He took office in 1878 with very strong popular support but it was his misfortune to be ruined by his Dominion political affiliations. The insistence by the Dominion government upon its right to disallow railway charters granted by the province and its refusal to grant ‘better terms’ in keeping with the province’s demands put the Norquay government in an impossible position.”

Friesen argues Norquay has not received the recognition he deserves from historians, many of whom have treated the former premier “as a minor bump in the road” in Macdonald’s nation-building endeavours.

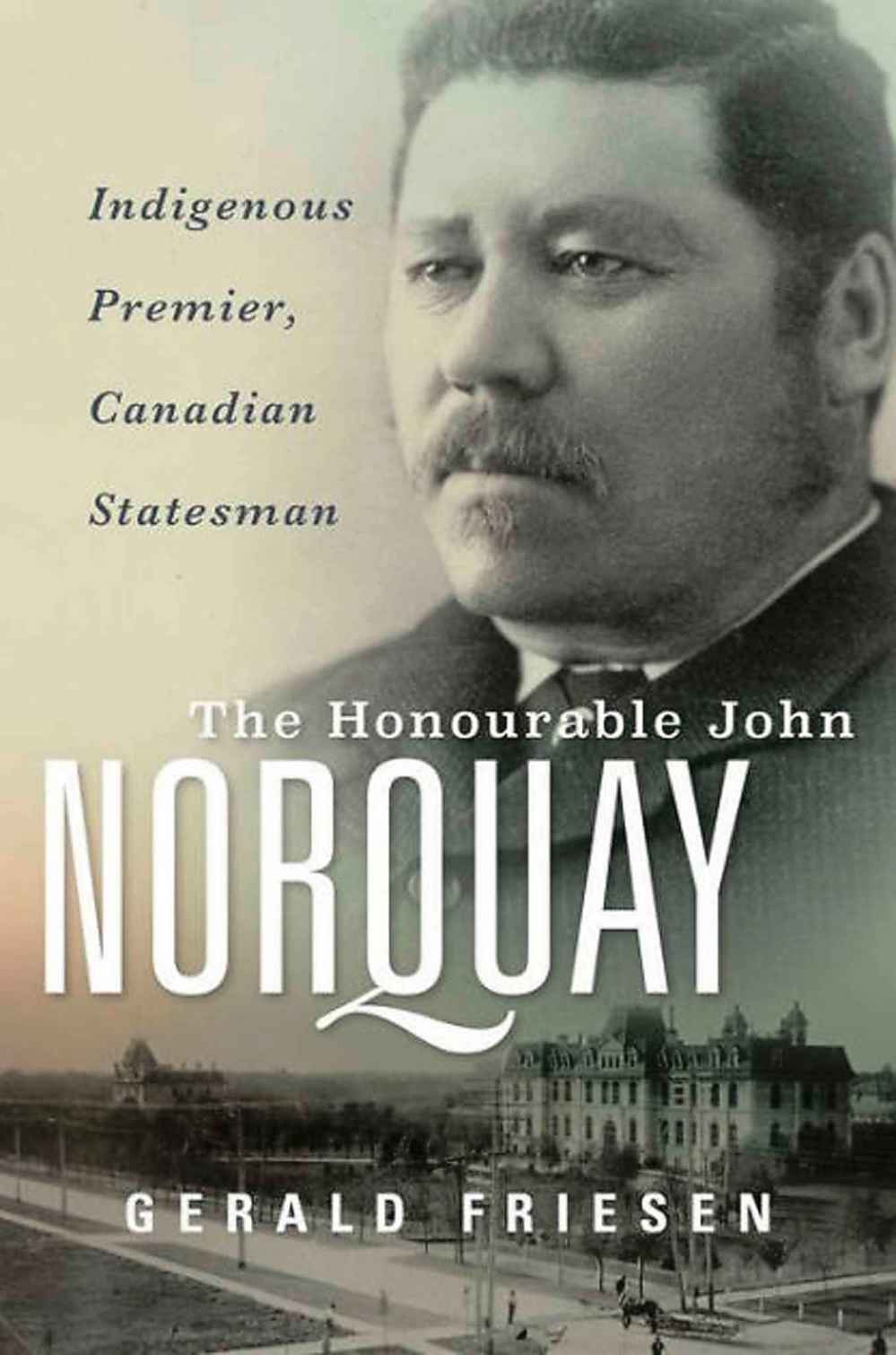

“Here’s a major national political figure who’s Indigenous and nobody knows anything about him,” said Friesen, whose book — The Honourable John Norquay: Indigenous Premier, Canadian Statesman — is scheduled to be released in April 2024. “He was a very impressive man… I think he was one of the great Canadians.”

Norquay was not only a significant player on the national stage, he played an important role as a bridge between the original inhabitants of Rupert’s Land — the Red River Métis, the Anishinaabe, Cree and other First Nations — and the new order of society Canada imposed on the West. As Manitoba’s first Indigenous premier, he helped manage and adjudicate the complex relationships that developed between the Métis, First Nations and non-Indigenous settlers in a way that left a lasting mark on Manitoba.

He recognized that racism and intolerance against Indigenous people were widely accepted at the time and he pushed back against them. But he also sought to balance those harmful elements with the benefits of Confederation in a manner he hoped would improve the overall circumstances of his people.

“Norquay saw both gains and losses in these attitudes,” Friesen writes in his book, an advance copy of which was obtained by the Free Press. “He celebrated Canadians’ participation in a global British imperial moment. But he also recognized that the country’s relations with Indigenous peoples were impaired by Ottawa’s disastrous policy choices and that racializing thought and racist rhetoric diminished the world in which he lived.”

“I think he was one of the great Canadians.”–Gerald Friesen

Most likely John Norquay had more to contribute to Manitoba and Canadian politics. Had he not died suddenly at a relatively young age — he was otherwise in good health — Norquay may have gone on to accomplish even greater things, perhaps at the federal level.

There was no shortage of challenging public-policy issues to tackle in the late 1800s, nor at the turn of the century, especially regarding the plight of Indigenous people and the manner in which they were mistreated in Canada.

Given his record and unique skill set, Norquay would have been well-positioned to seek out a more equitable and compassionate path than the one Canada ultimately took.

A Red River settler through and through

The term “Métis” was almost never used to describe an English-speaking person of mixed ancestry in the Red River Settlement in the 19th century. It applied almost exclusively to French-speaking and Michif-speaking people who lived largely on the east side of the Red River, including in St. Boniface and St. Vital, such as Métis leader Louis Riel.

But today, John Norquay — Manitoba’s first Indigenous premier who served from 1878 to 1887 — would identify as Métis, even though he was of Orkney-Scottish descent.

“There’s no doubt that he would be considered Red River Métis,” said Will Goodon, the Manitoba Métis Federation’s minister of housing and property management.

“Métis” has evolved over time to describe all people of mixed ancestry who trace their roots to the Red River Settlement, whether French-speaking or English-speaking, Catholic or Protestant.

“In today’s language, he would be called Métis, but in his own era, Métis were Michif-French speaking people, and he was not Métis, therefore, in his own time,” said retired University of Manitoba history professor Gerald Friesen. “But he was Indigenous and he did have mixed ancestry.”

The Métis culture and nation emerged from marriages between European fur traders and Indigenous women. Norquay’s ancestors were Scottish-Orkney and English Europeans who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Three of his great-grandmothers were born in northwestern British North America and descended from Europeans, Métis, Cree and Saulteaux.

Norquay was born in 1841 on the west bank of the Red River near present-day Lockport. Both of his parents died when he was young (his mother when he was two and his father when he was eight) and he was later raised by his paternal grandmother.

He spoke multiple languages, including English, French, Cree and Ojibwe as well as a local English dialect known as Bungee, a combination of many languages spoken with a distinctive rhythm and cadence. Norquay grew up trapping rabbits, fishing, farming and paddling canoes. He was a Red River settler through and through.

How he referred to himself beyond that is largely unknown. Norquay sometimes used the term “native” to describe himself. The term “half-breed” — although pejorative today — was used regularly in the 19th century to describe anyone of mixed ancestry. French-speaking Métis were considered both “Métis” and “half-breeds” (Riel and other Métis sometimes referred to themselves as half-breeds) and English-speaking people of mixed-ancestry were known simply as “half-breeds.”

MCCORD STEWART MUSEUM John Norquay didn’t emphasize his Métis ancestry the same way Louis Riel did,

The latter has a legal definition. When Manitoba joined Canada in 1870, the 1.4 million acres of land grants reserved for the Métis under the Manitoba Act was earmarked for the children of “half-breed” families, including Norquay, whose family received those land grants.

Norquay didn’t emphasize his Métis ancestry the same way Louis Riel did, especially later in his political career. Given the widespread anti-Indigenous racism that existed at the time, it was politically advantageous for Norquay to identify more with his European than his Indigenous ancestry.

“That was normal in those days,” said Kathy Mallet, a longtime Indigenous rights advocate in Winnipeg whose family lineage is connected to John Norquay’s wife, Elizabeth Norquay (born Elizabeth Setter). “If they could pass as a white person, they did — it was to their advantage.”

Mallet said there is no question Norquay was Métis. But she said it’s unlikely he would have used the term back then.

“I really don’t know what people called themselves because they were also Cree speakers,” said Mallet. “More likely half-breed was the term used at that time.”

Goodon said it’s not surprising Norquay downplayed his Métis ancestry given the anti-Indigenous racism that existed.

“That was a time when discrimination and racism wasn’t just tolerated, it was how things were,” said Goodon, who is Red River Métis and has been working with the MMF in many capacities since 1996. “It was a way to survive politically and likely financially and economically for him as a person.”

Many Métis downplayed, or even hid, their Indigenous ancestry at the time to avoid racial persecution, said Goodon.

MIKE THIESSEN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Will Goodon of the Manitoba Métis Federation said it’s no surprise John Norquay downplayed his Métis ancestry given the anti-Indigenous racism at the time.

Immediately after Manitoba joined Canada in 1870, many Métis were victims of murder, physical attacks and racial slurs by white newcomers during what became known as the “reign of terror.”

“Our people had to hide for generations after that,” Goodon said.

Norquay’s political accomplishments are particularly impressive considering the environment in which he governed, he said.

“Being visibly Métis or half-breed at the time, in spite of that, he was able to rise to the top,” Goodon said. “Even in today’s political world it’s an extra obstacle for politicians to overcome — I can’t even imagine what it would have been like back then.”

Norquay may have downplayed his Métis ancestry at times, but he never denied his Indigenous roots, said Friesen.

“In speeches in the legislature that are recorded in the newspapers, including the Free Press, he would insist that he was a native of Red River, he would talk about his countrymen — another word he used — and he would say he was proud of his heritage,” Friesen said. “There was one famous quote where he held up his arm and said there was Indian blood in this arm and Scottish blood as well.”

“He was a successful leader who won support across the population.”–Author Gerald Friesen

Norquay also fought for Métis rights while he was in office and often reminded his colleagues in the legislature of the unique place his “countrymen” held in the region as pioneers of the land. There were political advantages to doing so, since Norquay relied on the support of his English-speaking Métis constituents for re-election.

But there was also a genuine understanding by Norquay that the future stability and prosperity of the region was dependent upon the mutual respect and recognition of original settlers and newcomers to Manitoba. As the province’s first Indigenous premier, Norquay was uniquely positioned to advance that perspective.

That is something for which the former premier has not received the recognition he deserves, Friesen said.

“The fact that he was a great Indigenous leader I think makes a difference in this era when we’re paying attention, finally, to Indigenous reconciliation and the place of Indigenous people in the country,” Friesen said. “He was a successful leader who won support across the population.”

Goodon said the MMF still considers Louis Riel as their first premier. Riel was elected president of the second provisional government created during the Red River Resistance of 1869-70. He did not have the title of “premier,” but he was the executive head that governed alongside the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia. The assembly was made up of elected representatives — French-speaking and English-speaking — from all parts of the Red River Settlement in the months leading up to Manitoba’s entry into Confederation.

‘Treasure trove’ illuminates an amazing life

Gerald Friesen always knew he would write a biography about former Manitoba premier John Norquay. The University of Manitoba history professor, now retired, began researching Norquay and his political career in the 1970s when he was invited to write the Dictionary of Canadian Biography entry about the former premier.

“I knew his story was amazing,” said Friesen, whose new book — The Honourable John Norquay: Indigenous Premier, Canadian Statesman — is due out in April.

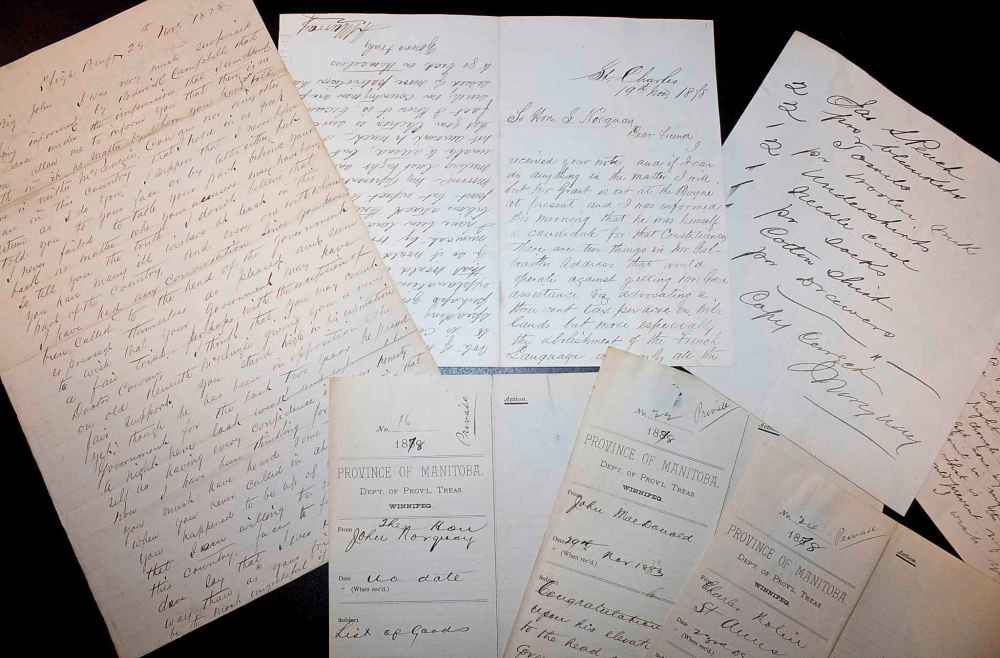

It was during those years of research he heard about previously undisclosed historical documents on Norquay that would soon become available — he just didn’t know what they were yet. Friesen would later find out it was a collection of letters, notes and other documents of Norquay’s stored in a trunk by family that few had ever seen.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Retired history professor Gerald Friesen looks over a plaque dedicated to former Manitoba premier John Norquay on the south grounds of the Manitoba legislative building.

The collection included handwritten letters to and from Norquay — some personal, others work-related — and other documents that would fill the historical gaps of Norquay’s career and of early Manitoba history.

The trunk was given to historian Ellen Cooke in 1946 by Norquay’s son, Dr. Horace Norquay, who lived in Selkirk at the time. Cooke, who had done a master’s degree at the U of M, knew the Norquay family and was planning to research his life and political career. But when her health began to fail, she negotiated with the Provincial Archives of Manitoba (now Archives of Manitoba) to have the collection transferred there for safekeeping.

It was around that time Friesen was told by then-provincial archivist John Bovey he may want to wait before writing Norquay’s biography because there were archival records that would soon become available he would be interested in. Bovey could not tell him exactly what those were because the archives didn’t have them yet.

“He knew what other people didn’t know: there was a huge collection of papers controlled by a woman, Ellen Cooke,” said Friesen. “He was negotiating to bring that incredible trunk of letters, mainly 4,000 letters and 3,000 other documents, into the archives… The negotiations took six years.”

It took that long in part because agreement was required on how to organize, store and preserve the documents.

MIKE THIESSEN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS A collection of historical papers relating to John Norquay was donated to the Archives of Manitoba in 1986, and includes thousands of documents, including letters to and from the former premier.

The collection was donated to the Provincial Archives of Manitoba in 1986, which the Winnipeg Free Press reported on at the time. Free Press columnist, the late Val Werier, interviewed Friesen about the collection and its historical significance in a piece published Feb. 15, 1986.

“There are a lot of gaps in the records of that period in Manitoba history marked by extraordinary social changes,” wrote Werier. “But now a new light will be shed on that era with the presentation of the official Norquay records and private papers to the Manitoba archives.”

Friesen had been compiling material on Norquay until then, but “that was nothing compared to this treasure trove when I found it,” he said.

It took many more years for the papers to be indexed and organized, which was done at the archives by Winnipeg historian Lee Gibson.

Once Friesen retired from the U of M 10 years ago, he began poring over the collection — which has been microfilmed — and used it to help write his new book, which will be published by the University of Manitoba Press.

The Norquay collection remains in storage at the Archives of Manitoba and is available to view on microfilm.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom Brodbeck is an award-winning author and columnist with over 30 years experience in print media. He joined the Free Press in 2019. Born and raised in Montreal, Tom graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1993 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and commerce. Read more about Tom.

Tom provides commentary and analysis on political and related issues at the municipal, provincial and federal level. His columns are built on research and coverage of local events. The Free Press’s editing team reviews Tom’s columns before they are posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press’s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Sunday, August 20, 2023 9:27 AM CDT: Fixes Norquay’s wife's maiden name

Updated on Monday, August 21, 2023 11:38 AM CDT: Fixes spelling of Will Goodon.