Prescription for dysfunction A decades-old cost-saving policy limiting the number of physicians in the province has left patients underserved and doctors overworked

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/09/2023 (865 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It was touted as a way to help cure soaring health-care costs.

A national task force studying medical resources in the mid-1980s came to the conclusion Canada had too many doctors for its population.

The solution, which sounds far-fetched today during a nationwide shortage of physicians, was to slash the number of doctors in training across the country.

Provinces were only too happy to get on board, with Manitoba pursuing cuts under NDP and Progressive Conservative governments throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

From his vantage point as dean of the University of Manitoba’s faculty of medicine at the time, Dr. Nick Anthonisen knew governments were making a mistake.

He joined a chorus of dire warnings to politicians who were looking to rein in health-care spending. Doctor associations predicted the perceived surplus would spiral into a critical shortage in the years to come.

“I don’t have a ‘told you so’ point of view, but we did tell them so,” Anthonisen, now retired, told the Free Press.

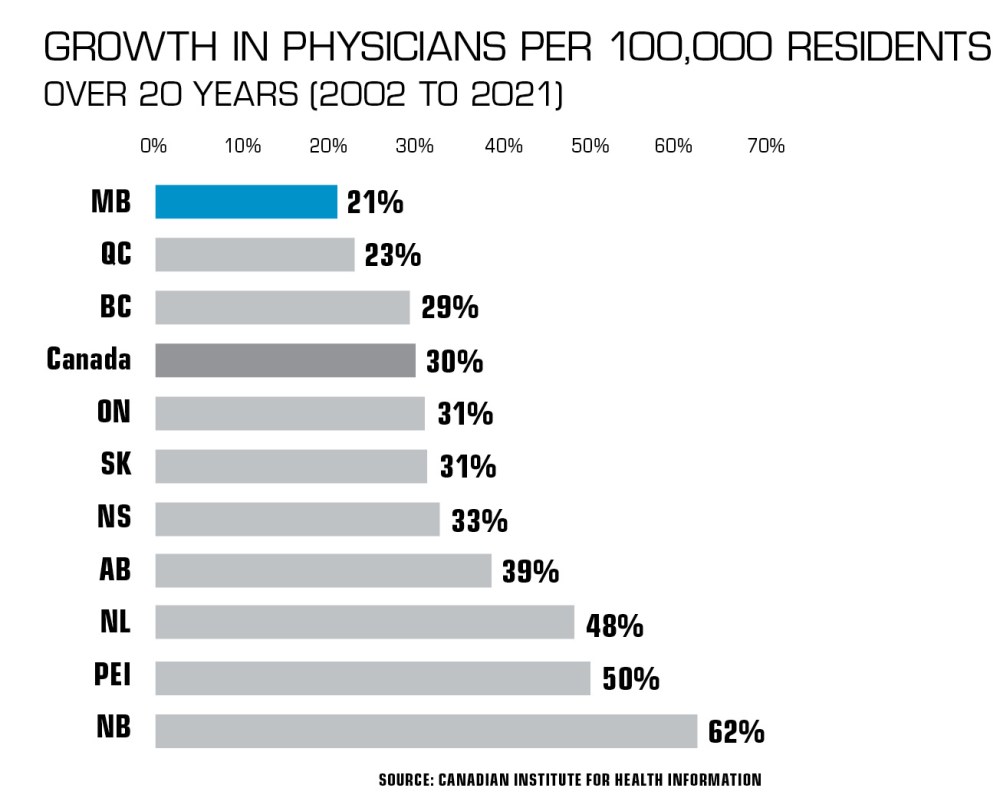

Today, those cuts, which resulted in nearly 800 fewer doctors being trained in the province, are cited as one of the main reasons Manitoba doesn’t have enough physicians for a population that is growing and living longer, with more complex medical needs.

“I think that was really the dominant factor,” said Dr. Peter Nickerson, the U of M’s current dean of health sciences and medicine.

Physicians who spoke to the Free Press also cited shortcomings in recruitment and retention programs, barriers for internationally educated doctors and retirements not being offset.

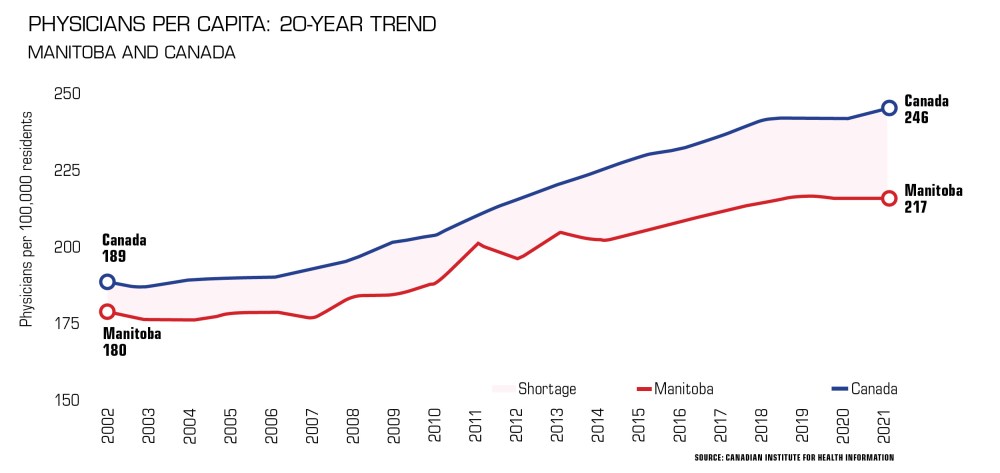

While it had been mounting for years, figures reveal Manitoba’s shortage has soared in the last decade. It hit an all-time high of 405 doctors in 2021, up from 359 in 2020, according to the latest data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

The legacy runs deep for patients who endure frustrating waits or long journeys for primary or specialty care, and for overwhelmed physicians who are experiencing unprecedented levels of burnout.

“I’m glad I’m not practising (today),” said Anthonisen, who specialized in respiratory medicine. “They’re swamped. They don’t have time to take care of what they ought to be taking care of.”

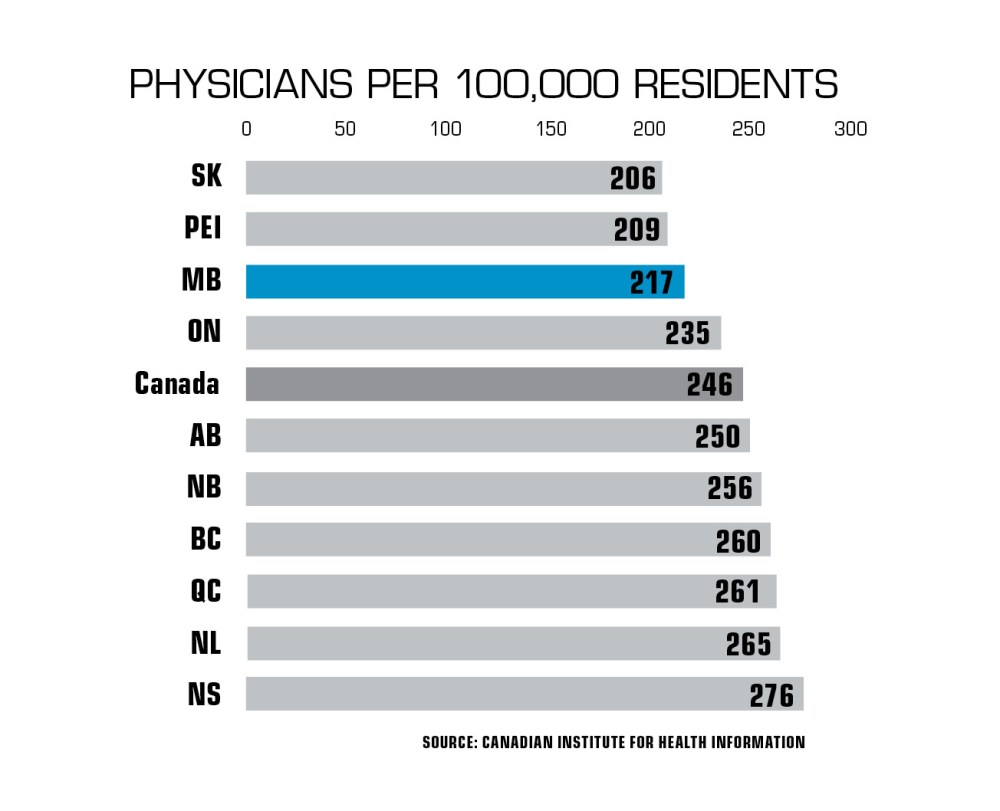

Manitoba is lagging behind most of Canada when it comes to doctors, data show.

It had 217 physicians per 100,000 residents — the third-lowest rate in the country — in 2021, CIHI found. The national average is 246 per 100,000. Two decades earlier, Manitoba had the fourth-highest rate.

While the health-care system continues to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, a provincial election on Oct. 3 could trigger more efforts to fill gaps and take pressure off doctors, nurses and other workers.

However, the next government will remain under significant pressure to find a way out of the crisis.

Despite a flurry of pre-election commitments and campaign promises, frontline staff say the end of sector-wide shortages is still years away.

For doctors, things could get worse before they improve. Politicians have been warned of an exodus as physicians retire, consider leaving Manitoba or scaling back their hours to achieve a healthier work-life balance.

It was always part of Dr. Nichelle Desilets’s plan to return home once she completed her training elsewhere in Canada.

With an interest in underserved populations, she wanted to be closer to her family in Elie, about 30 kilometres west of Winnipeg, while practising as a full-scope rural family physician.

Despite the shortage of doctors, finding work in Manitoba wasn’t simple. Desilets received just two replies after emailing regional health authorities.

“Prairie Mountain Health is the only one that engaged in a dialogue with me to find something that fit for a Manitoba-born physician who wanted to come home,” she said.

“It’s not easy to find a doctor job in Manitoba. I was a Manitoba-born, Canadian medical graduate who trained rurally, and I had to do a lot of work to get into contact with someone who would talk to me about getting set up in Manitoba.”

“It’s not easy to find a doctor job in Manitoba.”

That dialogue led to Desilets becoming one of seven physicians at the Beautiful Plains Community Medical Clinic in Neepawa, a growing town of about 5,700 people that is surrounded by rolling hills on Highway 16.

Desilets went to medical school at the University of Calgary and completed a residency in rural family medicine in Prince Albert, Sask.

“I decided that the variety in rural family medicine was really attractive,” said Desilets. “I got exposed to lots of really courageous and innovative doctors who worked in the country and did everything, and I thought that’s what I want to do.”

In Neepawa, where she has practised since 2015, she met her future husband, started a family and put down the kind of roots that keep doctors in rural communities.

Her practice was already full before her first day at the clinic. She now has about 900 patients on her roster, amid rising demand.

“We certainly don’t have as many doctors as is needed,” said Desilets. “We could comfortably double our numbers and still be fine. No one would be short on work.”

Desilets has kept a smaller practice because she has additional responsibilities at Neepawa’s hospital, where she covers the ER and performs some surgeries, and at a family-planning clinic in Winnipeg.

Her average work week is 56 hours. She sets boundaries to ensure a work-life balance and avoid burning out.

“The pressure is always to do more,” she said. “It’s hard to take on more patients when you feel that you’re at risk of already not serving the patients that you have.

“People want to feel like they’re working in a job where they’re making a difference, where the constant stressors and challenges aren’t outweighing the meaningful work that they’re doing. I think that’s where we’re really struggling lately.”

“We could comfortably double our numbers and still be fine. No one would be short on work.”

Physicians of the past used to work 70-90 hours per week and sacrificed time with loved ones. Usually, a spouse would take care of the household. Family dynamics have changed, and far more women are working as physicians.

“We want physicians to have a successful, satisfying job, which means they might work 50 hours a week,” said Doctors Manitoba president Dr. Michael Boroditsky, an obstetrician-gynecologist and assistant professor at the U of M.

“But, then you’re going to need more physicians to do the same amount of work.”

Dr. Candace Bradshaw, a family physician in River Heights, said the shortage is forcing people to work harder and faster, which is stretching some professionally and emotionally.

“It’s not something you can sustain for years and years without becoming tired, disillusioned and too fatigued to maintain any kind of balance,” said Doctors Manitoba’s board chair in an interview in July.

“You’re not able to provide the kind of care you know you were trained to deliver and that you know a patient needs. You’re just putting out fires all day long, and it is exasperating.”

Doctors Manitoba, an advocacy group that represents more than 4,000 physicians and students across the province, has expanded its programs that help physicians experiencing mental health or other issues.

A recent survey found 55 per cent of doctors were experiencing burnout, a record high.

Boroditsky said he has never seen morale this low among his colleagues. Doctors Manitoba has heard from members who do not feel valued or expressed concerns about being unable to spend enough time with patients.

He said health-care staff all have the same goal of providing timely, quality care to Manitobans.

“Patients are waiting too long to see us, if they can see us at all,” said Boroditsky. “That’s from a family physician perspective or even a specialist.

“And then when you do see them, you feel like you’re maybe not always at your best — you had to add in that extra half dozen patients because they’ve been waiting and everybody’s urgent.

“That just mounts the pressure that you have to provide quality care in a shorter amount of time.”

Desilets lamented the administrative burden that has been cited as a main driver of burnout. Physicians spend an average of 10 hours a week on tasks such as paperwork, according to a Doctors Manitoba survey, amounting to 1.4 million hours per year.

Many doctors own or co-own their clinics. Running a business in a time of escalating costs can bring its own stressors.

Bradshaw hears stories of orders or tests being missed due to heavy workloads, and physicians struggling as they take their work home with them.

“There are only so many things you can keep track of, and something eventually is going to give,” said Bradshaw.

“Unfortunately, that can mean patient safety issues — mistakes, errors, omissions.”

When Boroditsky graduated from the U of M in 2000, the number of doctor training seats in Manitoba had been frozen for more than half a decade.

The freeze followed a series of cuts that dropped the number of seats from 100 to 70.

Manitoba is still trying to catch up, and the gap could widen in the short-term. A survey by Doctors Manitoba earlier this year indicated 51 per cent of physicians are planning to retire, leave Manitoba or reduce their hours within three years.

Many of those now contemplating retirement were early in their careers when governments, believing the number of doctors had outstripped population growth, began targeting physicians by reducing seats at medical schools across Canada.

The U of M’s school admitted 101 first-year students in 1983, around the time a study conducted for the federal and provincial governments suggested Canada had a glut of doctors.

“They really thought they would have too many physicians [in the 1980s], and that’s never been borne out.”

According to Free Press archives, the study recommended cutting medical school enrolment by 17 per cent. Provinces began to follow suit, believing medicare costs would fall.

There was a lot of debate about the decision when Nickerson graduated from the U of M in 1986.

“They really thought they would have too many physicians, and that’s never been borne out,” he said.

Over a decade, NDP and Tory governments continued to cut the number of provincially funded seats. By 1990, there were 84 seats, said Nickerson.

The following year came a report by health economists Morris Barer and Greg Stoddart, which is often cited as a driver of further enrolment cuts across Canada.

Prepared for federal and provincial health ministries, the Barer-Stoddart report offered dozens of recommendations on medical resource policies to stabilize physician supply with the size of the population.

Governments seized on one suggestion in particular — reducing first-year enrolment by 10 per cent.

Anthonisen saw it purely as an attempt to reduce costs.

“The argument was that doctors bill, and if doctors bill, the health-care system costs a lot,” he said. “So, the finding was to reduce the doctors.”

After blame was directed their way, Barer and Stoddart complained in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in 1999 governments had ignored their warnings complementary policies would need to be adopted simultaneously. They said provinces ended up implementing very few of their recommendations.

At the U of M, enrolment plunged to its lowest mark — 70 — in 1994.

“This whole decrease that was occurring back (then), we’re now experiencing the consequences of it,” said Nickerson.

Annual admissions remained in the low 70s until the NDP hiked the number of seats to 85 in 2001. By 2007, the university had returned to its mid-1980s enrolment of 100.

After an increase to a then-record 110 in 2008, the number of seats was unchanged until last February, when the Tories announced additional funding.

The U of M welcomed a record 125 students when the new school year began in August.

Kiana Tait is one of 10 Indigenous students in the class of 2027. The class comprises 66 women, 57 men and two students who identify as non-binary. Almost 60 have roots, work experience or volunteer or leadership experience in rural areas.

Tait, 23, wants to become a family doctor and return to Norway House Cree Nation, where she was born and raised, to give back and inspire First Nations people, who are underrepresented in health-care professions.

Having taken an interest in medicine at a young age, she noticed early on a shortage of First Nations doctors and nurses.

“I didn’t see anybody like me, rarely, in the health-care system,” said Tait. “I wanted to create more representation.”

Tait said there is a lack of culturally safe care for Indigenous Peoples in Canada. She hopes to fill some of the gap.

“I want to incorporate Indigenous knowledge and Western knowledge while treating patients to help them feel more comfortable,” she said.

First-year classes will expand to an all-time high of 140 seats in 2024.

Nickerson said Manitoba will have 93 seats per one million residents at that time. It had 95.3 per million in 1983.

“Essentially, we’ve gone back to the levels that we had in the 1980s,” he said.

If class sizes had been kept at about 95 seats per million over the last 40 years, Manitoba would have trained an additional 770 doctors, said Nickerson.

The impact of expanded class sizes will not be immediate. It takes six years to train a family doctor. And that falls on the shoulders of practising physicians, who already have heavy workloads, Boroditsky noted.

“You need numerous people to teach one medical student,” he said. “It’s our pleasure to do it, but you need infrastructure and teachers, if you expand size of classes.”

About three-quarters of medical class graduates remain in Manitoba for their family medicine or specialty training.

The U of M hopes to one day have a satellite campus in Brandon to help train physicians for rural centres, said Nickerson, who specializes in kidney care.

To accommodate the additional graduates, the family residency program is being expanded from 52 seats to 82 over the next three years.

Seats are also being added to programs for internationally educated students.

The struggling health-care system — and party leaders’ promises to fix its problems — will be top of mind for many voters when they cast their ballots Oct. 3.

Between 153,000 and 208,000 people in Manitoba do not have a family physician, although not all are on a waiting list, said Doctors Manitoba, citing estimates from Statistics Canada, the Angus Reid Institute and its own surveys.

Bradshaw has seen that crush for demand personally.

The clinic she works at is “beyond capacity,” she said, with about 10,000 patients and facing an increasing number of requests from rural southern Manitobans who are struggling to find a family doctor in or near their home communities.

Multiple doctors said retaining existing physicians must be the biggest focus going forward.

“We can’t afford to lose more [physicians].”

“We can’t afford to lose more,” Boroditsky said in an interview before Doctors Manitoba ratified a new four-year deal with the province in August.

A $268-million funding boost for physician practices is designed to help ease the shortage by stabilizing services and supporting recruitment and retention.

The deal includes a new blended funding model, intended to increase patient rosters and incentivize physicians to spend more time with patients.

It replaces a decades-old fee-for-service model, which encouraged volume.

“That doesn’t work for today’s day and age where patients are more medically complicated and have multiple concerns per visit that they want addressed and we want to address, too,” said Bradshaw.

In multiple interviews, doctors said a new funding model would help to improve working conditions and provide better care.

“No one wants to join a sinking ship,” said Desilets. “If we can show that we have really robust retention strategies in place, I think that indirectly acts as a recruitment measure.”

The agreement aims to draw more physicians to rural and northern communities, provide more mental-health supports and continue efforts to reduce the administrative burden.

Ahead of the election, non-partisan Doctors Manitoba released a seven-point plan with recommendations to add 650 physicians and enhance care.

The organization requested an aggressive expansion of team-based care, with 250 additional health professionals in physician practices.

The NDP has promised to set up five more team-based clinics, which would put professionals such as mental-health experts and social workers alongside family doctors and nurses, to offer a broader range of care under one roof.

It has also pledged to meet Doctors Manitoba’s ask for 400 more physicians to reach the Canadian average of 246 doctors per 100,000 residents.

NDP Leader Wab Kinew said the NDP’s $500-million, four-year recruitment plan would add 300 nurses, plus rural paramedics and home-care staff.

So far, the Liberals have pledged to expand medical training seats, set up a Brandon campus dedicated to rural and northern areas, and eliminate barriers for foreign-trained health-care staff.

The PCs are still to unveil their campaign health-care pledges.

However, the Tory government rolled out commitments leading up to the election. One of the biggest announcements was a $400-million plan to add 2,000 health-care workers, retain existing staff and improve patient care. It includes the expansion of training seats at the U of M.

The PCs have faced much criticism for their record on health care — under premiers Brian Pallister and Heather Stefanson — since coming into power in 2016.

An Angus Reid survey in June suggested a majority of Manitobans was dissatisfied with the party’s performance on the health-care front — a total of 81 per cent of respondents said the Tory government had done a very poor or a poor job, while 17 per cent said it had done a very good or good job.

Before dissolution, the government hired Toronto-based Canadian Health Labs to recruit 150 family doctors (50 each for Winnipeg, rural communities and northern areas).

It also made regulatory changes intended to allow internationally educated doctors to start working sooner.

The College of Physicians and Surgeons said in a statement it has been working from a regulatory standpoint to make it easier to attract physicians to the province and to streamline and fast-track licensing requirements for out-of-province doctors and international medical graduates.

As for recruitment, Desilets said family medicine students tend to want to stay rural when they begin practising.

That speaks to the importance of recruiting efforts outside bigger centres, she said.

As rural communities take on a bigger role to entice doctors or nurses, it’s important to demonstrate that needs such as employment for partners, child-care spaces or housing can be met, said Desilets.

“You’re not just recruiting a doctor, you’re recruiting their family,” she said.

Dr. Chukwuma Abara started practising as a family physician in Thompson in 2017, after beginning his career in Nigeria.

He lives in northern Manitoba’s largest community with his wife and their two children, who were born in Thompson.

“One thing I really enjoy about working in the north is the opportunity to practise more broad-based primary care,” he said. “It’s very rewarding and fulfilling.”

When he arrived in 2012, he chose to settle in Manitoba because he had an uncle here and he believed the province would be the best fit, given his upbringing in a smaller city.

Abara is the medical director of Thompson’s primary-care clinic. He also works at the local hospital and travels to health centres in remote communities.

He said it is critical to maintain supports and funding to help recruit and retain doctors and their families in the north.

“Our biggest challenge in northern health care is the deep shortage of physicians,” said Abara. “Physician turnover here is high. Most people in the north that have left have done so due to their personal family circumstances.”

He said international medical graduates are being recruited as physician assistants in Thompson to give them exposure to and experience in the north.

The hope is they will return to Thompson or remote communities, when they are practising as doctors.

“Working in geographically isolated areas is not meant for everybody,” he said. “For those of us that have a passion for working in the north, that’s what we love to do. It’s where we want to be.”

chris.kitching@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @chriskitching

Chris Kitching is a general assignment reporter at the Free Press. He began his newspaper career in 2001, with stops in Winnipeg, Toronto and London, England, along the way. After returning to Winnipeg, he joined the Free Press in 2021, and now covers a little bit of everything for the newspaper. Read more about Chris.

Every piece of reporting Chris produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.