Houston: we have a solution Texas city’s housing-first approach has been widely lauded for tackling chronic homelessness. Can Winnipeg learn from its model?

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/03/2024 (691 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

HOUSTON — The bright Texas sun bears down on the cracked cement landscape behind a gas station on the city’s outskirts. Here, an elaborate makeshift structure shields its resident, a lanky man called Slim, from the elements — it can get cold at night, he says.

Slim is an open book. Sitting in the shade at the front of his shelter, he tells a reporter how his life went downhill just over a decade ago after the death of his wife. He met someone new, started using heroin with her, and ended up on the street. He desperately wants a home.

CALLAGHAN O’HARE / FREE PRESS Slim sits inside his makeshift home during a visit with members of the outreach team at the Coalition for the Homeless on Wednesday, February 14, 2024, in Houston, Texas.

His visitors this February day — members of the Homeless Outreach Team — hope to get him just that. Within an hour, intake forms are signed and Slim is one step closer to receiving a permanent residence.

This is the Houston model in action.

The sprawling Texas city is internationally regarded as a success story when it comes to addressing homelessness. So much so that politicians — and reporters — flock to the southern U.S. metropolis from other cities to learn how it works. Recently, Winnipeg Mayor Scott Gillingham was among those who made the trek. Manitoba’s NDP government has also expressed interest in the Houston model.

However, none of the visiting leaders have replicated Houston’s level of success in getting people housed and keeping them housed.

Since 2012, partners of the Way Home — the city’s homelessness initiative — have housed more than 30,000 people, with a 90 per cent success rate, meaning people did not return to homelessness within two years. This is a marked improvement from 2011, when Houston had one of the highest homeless populations in the U.S., at about 8,000 people. It’s since seen a 61 per cent drop in homelessness and today, there are about 3,000 people who are homeless, according to a recent survey. The area surveyed, and served by the Way Home, includes three counties within Greater Houston: Harris, Montgomery and Fort Bend, which have a total combined population of about 6.2 million.

The city has found success by taking a strict housing-first approach — meaning the priority is getting people into housing without any preconditions attached — supporting people with wraparound services, co-ordinating with all partners, being hyper-organized and ensuring data drives decision making.

Could Winnipeg learn from the city’s success? The Free Press travelled to Houston to find out.

The question was put to Kelly Young, president and CEO of the Coalition for the Homeless, the key group tasked with overseeing Houston’s homelessness mandate.

Her answer? Only if Winnipeg wants to.

“It’s a mindset,” she says of the buy-in needed to carry out an approach that at times didn’t make sense. “You just have to be willing to work through the absurdity.”

CALLAGHAN O’HARE / FREE PRESS Complete buy-in is critical, says Kelly Young, of the Coalition for the Homeless.

Young says the key ingredient in what might be regarded as Houston’s “secret sauce” is simple: co-ordination.

“You have to have all the players come to the table, you need to be clear about everybody’s agenda and you cannot deny other people’s agenda,” she says.

What that means is it doesn’t matter if you’re a concerned citizen looking to assist people who are homeless, a politician who wants to make constituents happy or a suburb-dweller who doesn’t like the look of encampments, she says. What matters is that you support eradicating homelessness — by getting people housed.

It also means everyone working to address homelessness — outreach teams, housing co-ordinators, police and the litany of groups at the street level — are all working together.

Houston didn’t get here by accident.

In 2009, the U.S. federal government passed an act requiring cities to adopt “housing-first” policies to access federal dollars. Groups addressing homelessness also had to start working together, sharing data and accepting oversight of one agency. Houston’s homeless rate was so high in 2011 that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development identified it as a “priority city,” a warning to figure out what it was doing wrong.

Houston accepted the challenge and ran with it.

The homeless response in Houston is called the Way Home Continuum of Care and the lead agency is the Coalition for the Homeless. There are more than 100 partners working under the Way Home umbrella, among them homeless service agencies, local governments, public housing, non-profits and community stakeholders.

However, it wasn’t easy getting groups with varying agendas moving in one direction, Young says.

She would know. Back then, Young was running an organization that housed people who were HIV-positive and homeless. Suddenly, she was being told her organization had to focus simply on housing people who were chronically homeless, meaning they were living on the street for more than a year, or were homeless repeatedly, and had a mental or physical disability.

“Every bed became a chronically homeless bed,” she says, and anyone outside that criteria moved down the priority list. “It was the craziest thing ever.”

Breaking down the silos caused an “uproar” in the social service world, Young says.

Now, however, she views the approach as the most “fair and just” thing to do; helping those who’ve been on the street the longest first. By moving people into housing regardless of what else is going on in their lives, the belief is they can stop living in survival mode and start feeling secure and able to tackle their challenges.

Young encourages other cities to unite stakeholders before they’re forced to.

“It wasn’t necessarily pretty,” Young says. “But at the end of it, because everybody had to do it, we figured out how to get along.”

Today, the work is data-driven, with all interactions and supports given to homeless people tracked to avoid duplication and to ensure they get the best help they need.

Another key plank of the Houston model: the housing is not just permanent, it’s “permanent supportive housing.” This means keeping people housed with wraparound supports, such as mental-health counselling, detox and food assistance, and assigning case workers to help along the way. These case workers can also act as intermediaries between landlords and tenants, addressing issues as they arise.

But first, connections have to be made. That’s where the outreach teams come in.

Jessalyn DiManno is wearing a black long-sleeved shirt with “Homeless Outreach Team” printed on the back in bold white letters. Jumping into an SUV in downtown Houston, the outreach manager joins two colleagues for a morning of work in the community.

The first stop is Slim’s shelter.

Slim knows the team well; he’s been homeless on and off for 12 years.

CALLAGHAN O’HARE / FREE PRESS The Homeless Outreach Team’s Jessalyn DiManno, Khena Minor and Fryda Ochoa begin a housing application process with Slim (left), who lives in a makeshift structure adjacent to a Houston gas station.

It’s clear life on the street has been hard on him. He talks about hearing gunshots at night, getting robbed and beaten up, being harassed by police, dealing with health issues including a golf-ball-sized cyst on the back of his head and feeling isolated from his family. He cries when he talks about not seeing his grandkids.

“I don’t want to be out here,” he says.

But the outreach team doesn’t force Slim to do anything he doesn’t want to do, even if that means he stays on the street when they could get him into housing.

He seems to wrestle with the idea that a different life is possible, even though he had stability and owned his own business in a past life. He feels stuck in a rut, he says. However, today he seems open to change.

Outreach worker Khena Minor pulls out an iPad the team uses to track all interactions with people who are homeless. She starts an assessment, asking Slim a range of questions, including his full name, how long he’s been on the street and if he has mental health conditions. This helps identify what housing programs he might be eligible for and also what support services he would need should he get into housing.

Sharing this information requires trust — and patience on the part of outreach workers trying to establish it.

“A lot of people have been defeated by the system before,” DiManno says. “They don’t trust us.”

CALLAGHAN O’HARE / FREE PRESS Slim hugs Jessalyn Dimanno, the manager of outreach for the Coalition for the Homeless.

She points to two folks setting up camp nearby. She asked for their last names but they didn’t want to share that information. The outreach team moved on, but they’ll probably come back, DiManno says, maybe offering a care kit with essentials like blankets, or seeing what else they may need.

“We’ll go get a burger if they want a burger,” DiManno says.

However flexible the outreach workers may be, the data-tracking system they work with is precise and accurate — to the point third-party verification is sometimes required.

This is what happens during Slim’s assessment. After Minor wraps up her questions, the foursome treks over to the gas station. They need someone else to verify Slim is, in fact, homeless. An attendant at the checkout counter who recognizes Slim is more than happy to do so, diligently filling out a form attesting to his homeless status while a lineup of customers forms. They can wait.

Before parting, Slim shouts “Happy Valentine’s Day!” to the outreach team. Everyone but him seems to have forgotten it’s Feb. 14.

As the outreach team drives to the next location, they keep their eyes peeled for others who are homeless. They know which piles of clothing and sleeping bags under freeways are new, and they seem able to see what the average passerby wouldn’t — a pile of items in tall grass is a hint someone lives there.

By another gas station, they spot a billowing tarp and a woman sleeping in its shade. They pull up and approach, apologizing for waking her, asking if there’s anything they can do to help.

CALLAGHAN O’HARE / FREE PRESS Slim’s shelter. He has been homeless on and off for 12 years.

Just then, a man abruptly exits the gas station and marches toward them. Everyone braces for a confrontation of some sort. Tensions die down when he explains he’s the gas station manager and says he keeps an eye on the woman. He tells her where to hide if law enforcement are coming by. He was curious to know who the team was and why they were there.

As DiManno and the man chat, Minor speaks with the woman and enters her information into the iPad. The woman tells her someone stole her phone and that she wants to connect with her mom, and possibly move in with her. She only has the number of her niece, though, which Minor takes down.

“Now I’ve got to do some digging,” Minor says, back in the vehicle.

Meanwhile, a young guy wearing a button-up T-shirt and backpack slowly approaches DiManno.

Quietly, he asks her where he can find a food bank, confiding in her — a stranger whose outreach team shirt is enough to prove she’s trustworthy — that he’s been in and out of jail and deals with mental health and substance use issues.

DiManno is glad to help. Too many people “fall through the gap,” she says.

Could this work in Winnipeg?

Mayor Gillingham sure hopes so, though he says the model would need to be tailored to fit Winnipeg’s needs.

“I really believe that if we’re truly going to make an impact in reducing homelessness, we need to have one co-ordinated approach,” Gillingham says.

He wants every group supporting homeless Winnipeggers “in one dragonboat,” paddling in the same direction, rather than in “separate kayaks,” doing their own thing.

“I really believe that if we’re truly going to make an impact in reducing homelessness, we need to have one co-ordinated approach.”–Scott Gillingham

Gillingham notes many city organizations do co-ordinate among themselves, “but Winnipeg is not yet at the place Houston is at, as far as one approach, one plan that everyone is … committed to.”

He says takeaways from his September trip to Houston included: all stakeholders — from non-profits to various levels of government to the private sector — are committed to a single co-ordinated approach; data is shared among all parties; the housing-first model, rather than temporary emergency shelters, is front and centre; and that a third party is responsible for program delivery, not government nor a front-line agency.

Winnipeg has around 1,300 people experiencing homelessness on any given day, according to a street census conducted in 2022, though experts believe the true number is much higher.

The provincial NDP, meanwhile, has also expressed commitment to bringing the Houston model to Manitoba, something they were vocal about long before last fall’s election. Now in government, they seem committed to following through, though details aren’t yet available.

In a statement, Minister of Housing, Addictions and Homelessness Bernadette Smith said the government hopes to end chronic homelessness. She said the Houston model offers lessons for how to implement the housing-first approach and providing wraparound supports.

“We are approaching this work collaboratively with all levels of government, community partners and those with lived experience and look forward to sharing more details after the upcoming budget is released.”

Back in 2010, before the city was committed to the Way Home response, the Houston Police Department formed its own dedicated team to help people who are homeless.

The police Homeless Outreach Team, or HOT, started with one sergeant and one officer, and has grown into a team of about 10 including a few civilians, such as social workers. They work in tandem with many of the same partners who fall under the Way Home umbrella, connecting people on the street to support services.

“We start with outreach,” says Derrick Fontenot, a sergeant with the HOT team. “We don’t do enforcement.”

His team is focused on building rapport with those who are homeless, trying to understand what circumstances led them to where they are today and asking how they can help.

They don’t want to throw people in jail, perpetuating a problematic cycle, says senior police officer Nick Vogelsang.

“When we’re able to find the barrier to the long-term solution, it breaks that cycle,” Vogelsang says.

“When we’re able to find the barrier to the long-term solution, it breaks that cycle.”–Nick Vogelsang

Asked why officers are the right people to carry out this work, Fontenot says he recognizes this is not traditional police work and that people might not always trust law enforcement. He says his team is committed to helping people and they have the training to go into situations that might be unsafe for other groups.

They also have the ability to issue ID cards to anyone who at one point had one in Texas, or who is in their database. This ID can be key for accessing social services or securing other personal documentation.

If there is one expert on housing and homelessness public policy in Houston, Marc Eichenbaum is it.

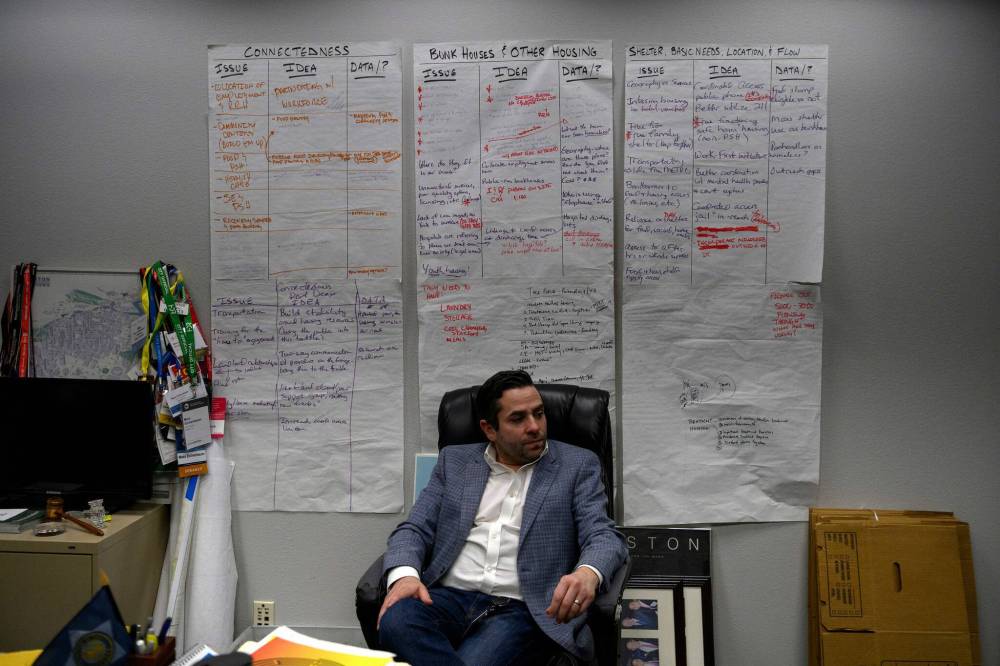

The longtime special assistant to the mayor of Houston for homeless initiatives, Eichenbaum knows the ins and outs and middles of everything homelessness-related. He’s got a slideshow with graphics and is ready to convince whoever walks through his city hall office doors that Houston’s approach to homelessness is the one to beat.

The approach, he stresses, is a pragmatic one.

“It costs money to keep homelessness at the levels that it’s currently at,” Eichenbaum says. “And it’s not enough to merely house individuals, you have to house more individuals out of homelessness every month than are becoming homeless to get a net reduction.”

CALLAGHAN O’HARE / FREE PRESS Marc Eichenbaum, the special assistant to the mayor for Houston’s homeless initiatives, says permanent supportive housing is the only solution.

In 2012, the city decided it didn’t want to tackle homelessness with transitional housing or shelters — keeping people living in survival mode with emergency health care and social services. Instead, it wants them in permanent supportive housing.

“Housing is the only way,” he says.

But it takes “major investment” to see success, he says. And hard work, commitment, partnerships and an overhaul of existing approaches.

The bulk of the funds supporting the initiatives in Houston are not coming from the city — they’re from the feds. City officials have used federal relief money provided after 2017’s Hurricane Harvey and COVID funds to keep clients housed. The Department of Housing and Urban Development provides tens of millions — US$59 million this year — to the Way Home’s initative on an annual basis. Additionally, the Coalition for the Homeless seeks out funds from other federal, state, local and private groups.

“Housing is the only way.”–Marc Eichenbaum

Eichenbaum says one of the first things the city and its partners realized in 2012 was that there existed sufficient housing supply for people who were vulnerable — but those who were chronically homeless weren’t first in line. Now, with the Way Home, there is one co-ordinated approach that triages and assesses and gets folks into the right accommodations for them, he says.

There’s another piece to Houston’s homeless puzzle: encampments.

Eichenbaum says residents also need to see the city’s approach is working. This means addressing tent encampments. The city works with its partners to “decommission” encampments, in the same way emergency shelters are decommissioned after natural disasters, Eichenbaum says.

With the Houston model, everyone in an encampment ends up housed, he says. Outreach teams come in first to connect with encampment residents, days later, they may be moved to what’s called the navigation centre as a living situation is worked out. Eventually, they get housing. And the encampment disappears.

The logistics of how and where people are housed varies, but when private landlords are involved, they may be offered incentives to house those in need. While some are reluctant to accept housing vouchers, it’s not uncommon for a bonus to be offered to a landlord to secure housing, Eichenbaum says.

“We believe that you can buy into your market,” he says.

Shalina Polkey is one of Houston’s many housing success stories.

After leaving an abusive relationship years ago, Polkey, who has a disability that makes it difficult for her to walk, found herself living in a car with her young son. They were in that situation for more than a year. It would have been longer if a flood didn’t destroy everything about six years ago. Polkey recalls swimming through her vehicle just to rescue important papers.

CALLAGHAN O’HARE / FREE PRESS For Shalina Polkey, with her son, Jabriel Polkey, 3, getting a permanent roof over her head was like winning the lottery.

Now, sitting in her sun-filled, three-bedroom, high-ceilinged townhouse, with her youngest son napping nearby, that life feels very distant.

“Now, I can breathe,” Polkey says. “It’s a blessing.”

She’s here because of help from Northwest Assistance Ministries, or NAM, one of the Way Home’s partners. After the flood, while living in a hotel paid for by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, she persistently called around, looking for anyone who could help her and her son, and she eventually connected with NAM. Within 30 days, the organization found her permanent supportive housing and covered her rent.

She moved again and has been in her new home for two years. She’s now working on getting her GED and wants to run her own home health-care business. Her rent is taken care of by NAM — which gets its funding from a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development grant — she gets social assistance and pays her own utilities and a case worker is in regular contact with her to make sure she has everything she needs. NAM even set her up with furniture.

Polkey has her dignity back, but she remembers clearly how demoralizing it felt to live in her vehicle with her son. She remembers how it felt to tell her son he couldn’t have his friends over.

CALLAGHAN O’HARE / FREE PRESS Polkey used to live out of a car. She now has a three-bedroom townhouse.

“That hurt a lot,” she says. “A lot of tears a lot of nights.”

As she tours a reporter and a photographer around her home, she talks with pride about how much she loves the bathroom she decorated, how her younger son is learning Spanish and how her older son is learning to cook. He is still at the rice stage.

Regardless of anything else, she’s grateful to finally feel safe and comfortable in a home with her family.

“Most people dream of winning the lottery. I just want a roof.”

katrina.clarke@freepress.mb.ca

Next week: Winnipeg stakeholders weigh in on the Houston model

Katrina Clarke

Investigative reporter

Katrina Clarke is an investigative reporter at the Winnipeg Free Press. Katrina holds a bachelor’s degree in politics from Queen’s University and a master’s degree in journalism from Western University. She has worked at newspapers across Canada, including the National Post and the Toronto Star. She joined the Free Press in 2022. Read more about Katrina.

Every piece of reporting Katrina produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, March 1, 2024 9:04 AM CST: Changes subheadline

Updated on Friday, March 1, 2024 3:13 PM CST: Fixes typo