Love thy clear-eyed neighbours People living and working near a 66-bed men's addiction rehab facility in Calgary say Sturgeon Creek residents will have nothing to fear -- and plenty to appreciate -- when the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre opens its doors

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/03/2019 (2461 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Not in their backyard. Build it somewhere else.

Opponents of a proposed addictions treatment centre in a west Winnipeg neighbourhood wasted little time in organizing efforts to kill it. Dozens wore white in protest and carried placards to public information sessions punctuated by raw emotion and flashes of anger.

Letters of objection were sent to city hall, where attempts to block the facility with zoning appeals were exhausted.

When the ground is broken on the site of the permanently closed Vimy Arena this summer to signal the beginning of construction, the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre will become a reality for Sturgeon Creek residents confronted with the spectre of addicts moving into their quiet community.

Will they pose a danger, especially to children? Will criminals involved in the illegal drug trade be drawn to the area? Will property values take a hit?

The answer is an emphatic “no,” say people who live and work near a similar facility in Calgary.

“Don’t be afraid,” says Jacqui Esler, executive director of the Calgary business improvement zone where Simon House Recovery Centre has been located since 1983.

“They might have tattoos and piercings and whatever, but these guys are great for the community.”

“These guys,” say Esler and a host of other community members, shovel neighbours’ snow and cut grass free of charge. They volunteer at bingos and street festivals. They cook and serve a monthly brunch attended by more than 150 people from the community.

They staff the community’s annual bike race, arriving at 5 a.m. to erect street barriers. In the days before Halloween, they distribute pumpkins to area businesses. After Christmas, they scale trees to take down Christmas lights in retail areas.

They help churches erect tents for garage sales. A local yoga studio doesn’t charge them to attend classes so, as a thank-you, they installed new flooring and drywall there. A hair salon offers the recovering addicts free haircuts and, when it snows, they hurry to clear the pavement outside.

Police have never been called to Simon House. None of the centre’s neighbours has ever reported trouble from one of the recovering addicts.

In her four years of encounters with the men undergoing treatment in the 66-bed facility, Esler hasn’t met any who were high on drugs or acting improperly.

“Whatever they feel they have taken from the community, whatever they’ve taken from their families, they want a chance to give back,” she says. “Giving back to their community is a big part of their mandate, a huge part of their rehabilitation.”

The Bowness Seniors Centre, which is about five blocks from Simon House, has benefited immeasurably from the recovering addicts’ zeal to give back. They shovel all the snow that falls on the centre’s two parking lots and sidewalks. They cut grass, trim hedges and do renovations. They recently captured a panicked squirrel that was creating havoc under the centre’s roof.

In return, the centre allows Simon House residents to use the facility for their regular graduation ceremonies.

The recovering addicts also cook and serve a brunch at the seniors’ centre on the second Sunday of every month. They invite everyone from surrounding neighbourhoods and keep the price break-even low at $10 a person, so entire families can attend. They typically feed 165 people, and more than 250 on special occasions such as Mother’s Day.

“This is one of the ways they actually bring the community together,” says Sheila Clayden, a seniors centre past-president who has interacted with “the boys” for 16 years “without any problems.” They call her “Moms” or “Mamma Bear.”

“We see the changes so much, from when they first come in — some of them broken,” she says. “And as the weeks go on, it’s almost a miracle how much they change. They’re so proud of their sobriety chips.”

Clayden has attended the funerals of some men who couldn’t bear sobriety and left the recovery program. And she’s also had the joy of seeing long-recovered Simon House grads return — clear-eyed — to the seniors centre to proudly update her on their healthy lives and introduce her to their newborn children.

“Some come from communities where they were never valued, except for their drug use. Their recovery depends on getting accepted by a different community and finding out they are valued for who they are.”

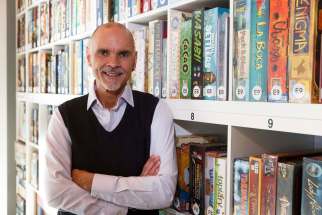

Simon House CEO Trevor Loria, who has 21 years of experience in the field of addictions and mental health, says he’s not aware of any research that shows an increase in criminal behaviour in communities where recovery centres are located.

“They’re clean and sober,” he says. “They’re not walking around like zombies who are high. And if they do relapse, the community around the recovery centre is the last place they want to stay.”

People who own houses near the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre’s Hamilton Avenue address need not worry about property values, he says. Homes close to Simon House start at about $500,000 and many crack the $1-million mark.

Loria is well-acquainted with the negative stereotypes about recovering addicts that fuelled much of the opposition campaign in Winnipeg. But in a letter of support he wrote for the Oake centre, he said that positive community connections are crucial to the recovery of addicts; they must break free of people and activities that revolve around alcohol and drugs, and establish new connections that are wholesome, he says.

“People seeking recovery from their addiction do not succeed if they are stigmatized and judged by their community,” he says.

The Winnipeg facility plans to adopt the protocols that have worked for well for Simon House: men are there of their own volition, adhere to abstinence-based programs, are supervised 24 hours a day and tested regularly for illicit substances. The regimen includes rigorous application of the 12-step program, which demands fearless introspection and making amends to other people.

A top priority is interacting in positive ways with the centre’s neighbours.

“Their inclusion in the community is the point to the facility being in a residential area,” says Hockey Night in Canada broadcaster Scott Oake, the tireless, passionate promoter of the non-profit, 50-bed Winnipeg facility for men.

“They will become good neighbours willing to lend a helping hand. Our hope is, as time goes on, even the most ardent opponents will come to realize it’s a benefit to their community.”

Although the capital fundraising campaign for the $14-million Winnipeg centre doesn’t officially start until May, money is already flowing, including a $300,000 contribution made March 16 at the Sons of Italy Gala Dinner. There have been envelopes with $20 inside from people who typically include poignant notes explaining they’re making the donation on behalf of a loved one struggling with addictions.

Oake said the groundbreaking will be Aug. 22, a date that is firm and purposeful; it would have been the 34th birthday of his son Bruce, who died at age 25 of a heroin overdose, and whose name will live on atop the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre.

carl.degurse@freepress.mb.ca