‘They’re waiting for the Titanic to go down’ Front-line health-care employees speak out on crushing weight of COVID-19 pandemic, damage to fragile system

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/12/2021 (1437 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

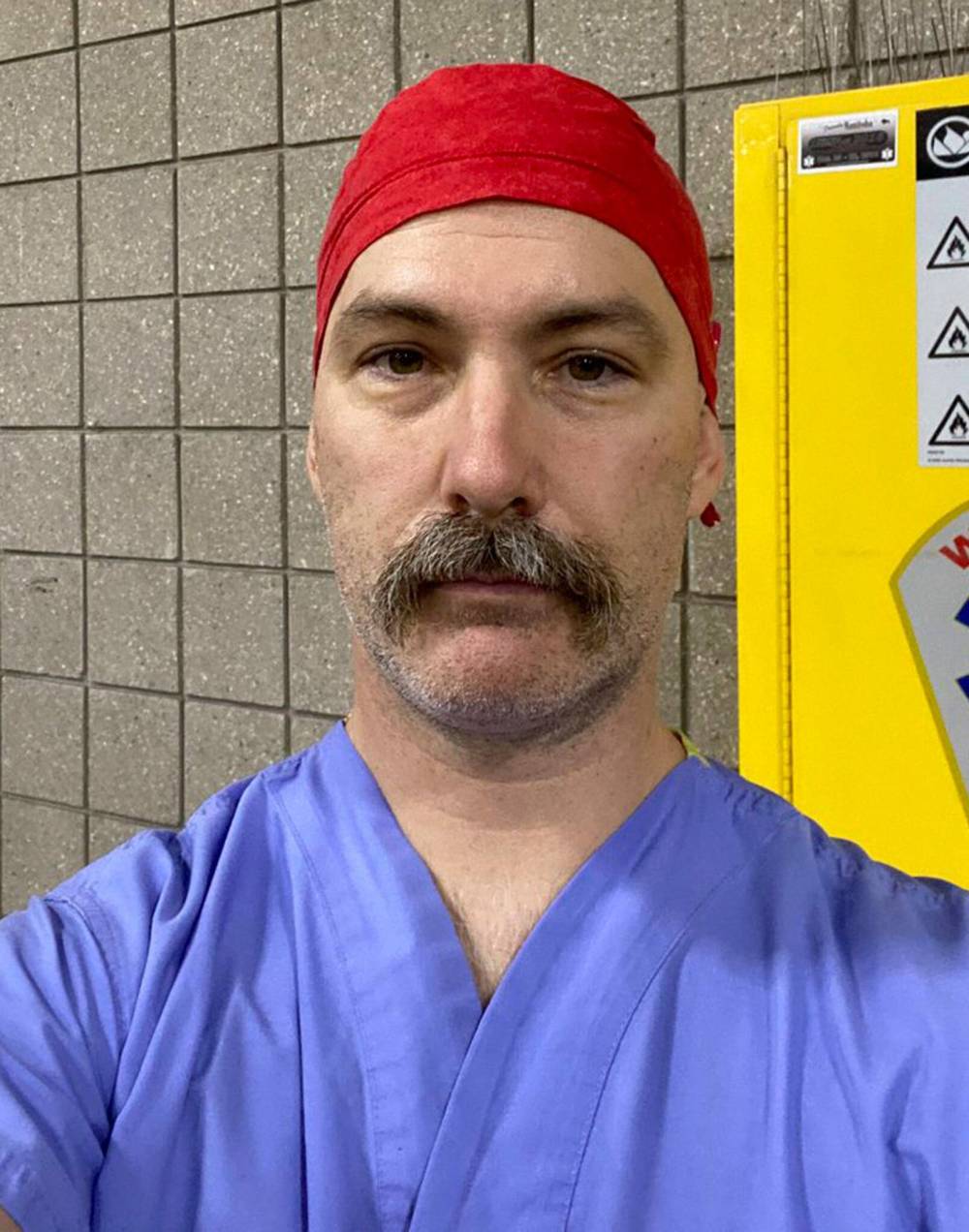

Craig Doell doesn’t know how to answer when patients ask him if they’re going to die.

His decades of work as a respiratory therapist never prepared him for putting so many people into a coma, so a ventilator might give them a chance at recovering from COVID-19.

“You can’t sugar coat it. How many times I have been asked by people, ‘Am I going to die?’ and I can honestly tell them: ‘I do not know.’ That doesn’t get easier every day,” said Doell, who works at the Boundary Trails Health Centre, located between the southern cities of Morden and Winkler, Manitoba’s epicentre of COVID-19.

“You can be 30 years old and the odds are stacked in your favour, but I can’t guarantee anything, with this kind of bug it’s not predictable,” he said.

“It’s hard when it’s so preventable.”

As officials sound the alarm about the Omicron variant set to take over hospital capacity, the Free Press spoke with four front-line medical workers about bracing for a surge and how Manitoba’s health-care system ended up in such a critical state.

“Never in my life did I think I would be privy to so many patient conversations between family members over the phone, crying or watching people as they’re getting sicker — praying, hoping for hope, that they don’t have to be going on a ventilator,” said Doell.

“A lot of people don’t realize until it’s very late how serious this is.”

In the Southern Health region, misinformation has been a key driver of COVID-19 spread since early in the pandemic.

It’s worsened since Labour Day. Cases have been on the rise, and Doell said a majority of COVID-19 patients at the hospital have tried to take things into their own hands and ingested ivermectin.

A preliminary study suggested a human version of the horse-dewormer drug might make COVID-19 infections less severe, which anti-vaccination groups latched onto. But much more research has shown the risks far exceed any possible benefits.

“It’s rampant around here; for the most part, we’re very surprised if people are not taking it,” Doell said of the antiparasitic developed in the 1970s.

“It used to be a question of, ‘Are you taking this?’ and it’s now, ‘How much of this are you taking?’”

Doell said these patients aren’t the people who show up at anti-vaccination protests. Instead, they read something on Facebook from someone they trusted, instead of listening to doctors.

COVID-19 patients who arrive at Boundary Trails have often never been tested, making it nearly impossible for officials to anticipate hospital workloads and ICU needs.

Instead, they come in two weeks into a COVID-19 infection; by which point, they often have to be put on a nasal prong (an oxygen tube that runs under the nose) in order to keep them cogent long enough to talk about the possible need for a ventilator.

“They’re mothers or fathers — they’re parents and have parents themselves, and sometimes we have really young people,” Doell said.

“You can’t sugar coat it. How many times I have been asked by people, ‘Am I going to die?’ and I can honestly tell them: ‘I do not know.’ That doesn’t get easier every day.”

– Craig Doell, respiratory therapist

Some patients don’t want to go on a ventilator, after reading the machine might kill them, when the reality is it’s their best shot at keeping alive while their body tries to cure itself.

Sometimes, they beg for a vaccine dose, but that won’t help them so late into an infection.

Earlier this month, Doell worked 22.5 hours to help to transport three patients to the ICU at Health Sciences Centre in Winnipeg in bad weather.

Only a few sent to Winnipeg or Brandon return to the Boundary Trails rehabilitation wing; most of them complete treatment in the ICU.

“We don’t get any closure on whether they lived or died; there’s a lot of us left wondering what happened to these people,” Doell said.

At the start of the pandemic, there were social media postings about the hospital’s empty parking lot and waiting rooms, which don’t account for the facility barring visitors, and private rooms crammed with patients on ventilators or oxygen.

Doell said the public doesn’t notice ambulances leaving the hospital with sirens on and coming back quiet, because they’re sending patients to ICUs, as are the helicopters that sometimes come multiple times a day.

When he’s pointed this out on social media, he’s had harassing voicemails.

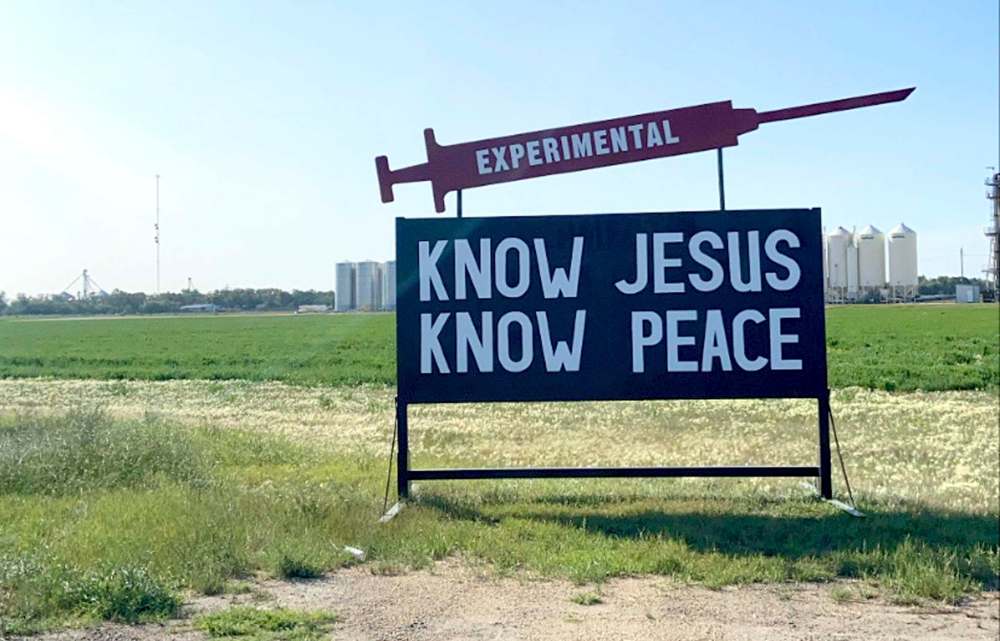

In the summer, he cycled to work from his Morden home, passing a sign that called COVID-19 vaccines “experimental” and urging people to “Know Jesus, Know Peace.”

Doell doesn’t want to focus on criticisms the province isn’t cracking down enough on clandestine church gatherings. He instead wants to highlight the work of politicians like Morden Mayor Brandon Burley, who has encouraged people to get a shot.

“Public health should never be politicized, and that’s what it became, and it’s a big barrier,” said Doell.

He said vaccine mandates for activities such watching children play hockey have enticed people to get a shot but, sadly, so has people seeing relatives die.

“There have been a lot of tough lessons learned.”

Doell said government officials have tried hard — hosting information town halls, having vaccine medical task force lead Dr. Joss Reimer in awareness campaigns, and doctors having individual conversations with patients.

“It’s obviously not getting through to a lot of people.”

Doell worries about the Omicron variant’s ability to reinfect people, given how many in the Southern Health region already caught COVID-19 and plan to rely on natural immunity.

His colleagues try to stay positive. His wife and kids make him waffles. He takes his two dogs on walks to de-stress.

“We want people to live long, happy lives,” Doell said after a Friday nap; he’d finished his last shift at 2 a.m. “You see a lot of things, and we’re tired.”

● ● ●

Dr. Renate Singh is tired of cancer patients having their surgeries delayed.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the anesthesiologist has had a front-row seat to the best and worst things about Manitoba hospitals.

She’s seen doctors, nurses, health-care aides and respiratory therapists come together — and burn out.

“The willingness to lend a hand and help each other — that, to me, has been the high point; it reminds me why I love the hospital environment,” she said. “At the same time, it wounds me very deeply to see this level of compassion fatigue.”

Singh says both recent NDP and PC Manitoba governments are to blame, with the former commissioning consultant David Peachey in 2015 to design a health-care reform that the latter executed.

The plan was to get unsustainable health-care spending under control, but experts argued the recommendations didn’t fit Manitoba’s tertiary and acute care needs.

“They began a process of basically dismantling any capacity we had to deal with any sort of surge,” she said. “Prior to the pandemic, we were operating pretty much close to capacity all the time; once we got a surge it was impossible to be able to keep up.”

The result is that colleagues put in 16-hour shifts day after day, particularly nurses who went without a union contract for years.

“I don’t think the public truly understands how maligned nursing has been in this pandemic,” said Singh, who splits shifts between the Grace Hospital and HSC Winnipeg. “I’ve seen a lot of early retirements and resignations from the profession.”

Those who do stay on the job are often pulled from their wards to help COVID-19 patients in ICUs.

The knock: one result is delayed surgeries, particularly for colon, breast and pancreatic cancers.

“You try very, very hard to advocate for your patients and get them care, only to be hit by the reality that there’s not always a bed to put them in and there’s not always staff available to perform the procedures,” Singh said.

In trying to prevent burnout, a patient with a fracture from five days ago is asked to wait another day for care.

“We push ourselves to the brink and work as many hours as we possibly can, in order to make this happen. But all the same, there are just not enough bodies to make this achievable.”

“You try very, very hard to advocate for your patients and get them care, only to be hit by the reality that there’s not always a bed to put them in and there’s not always staff available to perform the procedures.”

– Dr. Renate Singh

The lowest point for Singh was in May, when Manitoba became the first province to send ICU patients to other jurisdictions for care.

“To see our system deteriorate to the point that we needed to do that, was a real kick in the stomach to me; it was a real knife in my heart.”

A task force is underway to deal with the surgery backlogs, but everyone know it will take years to train and hire nurses.

Singh described this wave as scaling a mountain, with the summit being reached either by gradually pacing to each level or a sudden ascent that will leave many behind.

Vaccinations will prevent severe cases of the highly contagious Omicron variant, and some exposed to it won’t even get infected. But the unvaccinated could be hit hard. New public health restrictions aim to slow that process.

“With Omicron coming, everybody who has not seen this virus before is going to see it, and mount some sort of immune response to it,” she said.

Still, front-line health-care workers are exhausted. On the clock, they constantly play catch-up in an overstretched system. Outside of work, they’re writing open letters, giving interviews, meeting with officials and advocating for patients.

It’s no wonder so many are leaving medicine all together.

“They’re waiting for the Titanic to go down, because they’re resigned to the fact that it is and everybody is grieving what we’ve lost.”

● ● ●

Dr. Christine Peschken keeps trying to convince her patients to go to the hospital.

As head of rheumatology at HSC, almost all of her patients are immunocompromised and have complex needs.

“I’m talking to them, saying you need to go to the emergency room, and they’re saying, ‘I don’t want to do that’ — because they’re frightened of what will happen when they get there; they know what it’s like on the wards.”

What that looks like seems chaotic to her. Hospitals have pulled staff from other wards, who have been replaced by clinicians from other services.

“We are all being asked to pitch in, so we have a real domino effect,” she said. “Everybody’s doing their best, but when people are doing care that is not in their usual expertise, it’s not going to be as good. There’s no way around that.”

Her patients know, so when someone with lupus or complex arthritis needs care, they often try to stay home.

Peschken was among 10 Manitoba experts who signed an open letter this week pleading for increased public health restrictions, some of which the province announced Friday it would implement as of Tuesday.

The letter warned that doctors will have to soon triage patient care, rationing medical attention on those most likely to survive.

They’re not the only ones predicting such a scenario. This week, the Canadian Medical Protective Association, which provides legal counsel for physicians, sent out a reminder about its guide on legal liability for when provinces activate triage protocols.

Peschken was encouraged Manitoba asked Ottawa last weekend to send ICU nurses to re-enforce efforts, but she fears there will still be a catastrophic increase in cases because the new restrictions will have come so late.

“I cannot pretend to have a lot of optimism right now; we have a few tough weeks ahead of us,” she said. “Before Omicron, we thought we were going to have a slow increase and (wondered) how we were going to cope with that.”

In every wave of COVID-19, Manitoba has seen trends weeks later than other provinces. And while the province was proactive in rolling out a proof of vaccination and procuring rapid tests, it’s often been among the last to implement restrictions to slow transmission.

“We should have the advantage of looking around us, and saying, look what happened; what can we learn from that (and) what can we do differently,” she said.

“Almost all the time, we have not done that.”

● ● ●

Dr. Doug Eyolfson felt hopeful just two months ago, for the first time in years.

After Tory premier Brian Pallister resigned in the summer, his potential successors promised to listen. This fall, Manitoba avoided the large fourth wave its Prairie peers endured, by keeping restrictions and a vaccination mandate.

But that only went so far.

The ICU ward at Grace Hospital in Winnipeg has been maxed-out for weeks.

“We’re full. As soon as we discharge someone, there’s always someone else to fill the bed,” said the former Liberal MP. “You’re just forced into a situation where you’re not giving as good care as you should be giving.”

He can’t fathom why Premier Heather Stefanson has refused to follow other provinces by requiring personal care home workers to get vaccinated.

“I was white-faced with anger when I read that,” Eyolfson said, noting 56 people died in the Maples personal care home outbreak (October 2020 to January 2021).

“The anger is that this was largely preventable.”

– Dr. Doug Eyolfson

Meanwhile, cases have been on the rise in the Southern Health region, where the government has been loathe to criticize illegal church gatherings.

At the Grace, Eyolfson said cancer patients are getting tests that had been delayed by a year and, “Now it’s either not operable or just beyond any type of cure.”

Eyolfson hopes new restrictions will stem the worst, and he’s hopeful the request for federal nurses will help delay the worst.

But he can’t shake the resentment that replaced his hope earlier this fall.

“The anger is that this was largely preventable.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca