Breezy, accessible modern art history

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/11/2012 (4718 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

As a former media director of England’s prestigious Tate gallery, Will Gompertz has been a front-row witness to what he calls “a central tension in the art world: public engagement versus scholarship.”

Clearly the 47-year-old Brit is trying for a bit of both in his debut book, a breezy, accessible and educational history of modern art.

The Oxford-based Gompertz starts with a shout-out to two previous historians of art, E.H. Gombrich and Robert Hughes. While Gompertz can’t manage Gombrich’s intellectual depth or Hughes’s incisive edge, he is a genial popularizer. Having worked as the BBC arts editor since 2009, he knows how to write jargon-free prose for a general audience.

The book had its genesis in a one-man show Gompertz performed at the 2009 Edinburgh Fringe. It’s not surprising, then, that he often favours anecdotes over analysis. He explains how Matisse’s and Picasso’s frenemy relationship helped to kick-start 20th-century modernism, for instance, and gives an entertaining description of a fist fight between Tatlin and Malevich over the coveted corner spot in a 1915 exhibition of Russian abstraction.

Gompertz has a knack for making contemporary connections, as when he describes Henri Rousseau, a provincial painter with a naive style who was picked up by Paris’s avant-garde, as “the Susan Boyle of his day.”

But he often strains after relevance. Is there really a direct line from analytic cubism “to the Modernist aesthetic of stripped pine floors?”

And sometimes Gompertz tries way too hard to “get down with the kids.” (We’re pretty sure no one over the age of 23 should use the expression “rocked up.”)

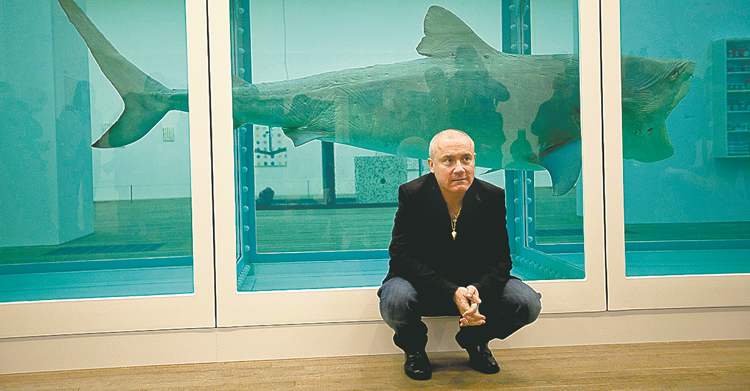

The book does benefit from its comprehensive timeline, which starts with the 19th-century French realists and goes right up to Damien Hirst, his swaggering pickled shark, and the contested period of late contemporary art that Gompertz calls “Entrepreneurialism.”

Here Gompertz’s Brit-weighted emphasis makes sense, since Hirst and his cohort of Young British Artists really were at the centre of the hyper-accelerated global art market and the blurred realm of “artertainment” (a terrible, terrible word, even as neologisms go).

The book’s scholarly high point is a passionate, eloquent chapter on Cezanne, in which Gompertz offers a close reading of key works to explain why the reclusive painter was considered by Matisse and Picasso to be “the father of us all.”

But Gompertz often skimps on larger historical and social frameworks. We could use more on the shattering effects of the First World War, or on humankind’s ambivalent relationship with modern technology, which runs through 20th-century art like a double-edged knife.

But the book’s greatest problems probably come down to the current economic state of publishing. Gompertz could use a stern copy editor. And there simply aren’t enough visuals — only 29 small colour plates for 150 years of art, along with some grainy black-and-white illustrations.

It’s hard to feel “the shock of the new” of a Fauvist landscape, for example, when Gompertz is reduced to written descriptions of how crazy the colours are.

Public engagement and scholarship are more effective with pictures.

Alison Gillmor is a Winnipeg arts writer.

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.