New HQ couldn’t come soon enough for cramped police

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/04/2016 (3445 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The 1960s was a decade of great change in the city hall district of Winnipeg.

Until that time, most of the city’s services were headquartered in a collection of turn-of-the-century buildings located within a couple of blocks of each other. There was the old city hall with the market building, which had been converted to civic offices in 1919, located behind it. The central fire hall was situated on what we now know as Old Market Square Park.

“The six-storey, 117,906-square-foot PSB was initially dubbed the Fortress in some media articles, and that appearance was no accident.”

Few doubted a new headquarters was needed

The Central Police Station on Rupert Avenue was the newest of the civic buildings. It was built in 1908 and expanded in 1911 to house a projected police force of 180 officers. By the late 1950s, though, the department consisted of nearly 450 officers and about 100 civilian staff. The men’s jail, with a capacity of 40, regularly held between 65 and 90 prisoners. Technologies not thought of when the building was constructed — such as traffic-signal control, radio dispatch and a 999 emergency call centre — were shoehorned in whatever space could be found.

Police chief Robert Taft, the leading proponent for a new central police station, complained at one police commission meeting: “I’m getting frantic. The jail is overcrowded, and my help are sitting in each other’s lap. We may lose competent, well-trained help.”

Few doubted the need for a new police headquarters, but it was going to have to wait until a site for the new city hall was chosen. The front-runner location through the late 1950s and early 1960s was across from the legislative building. Today it is Memorial Park, but at the time it was home to an array of University of Manitoba buildings that were slowly relocating to the institution’s Fort Garry campus.

It was assumed when the new city hall was completed, the police station would be built on the site of the old city hall.

To prepare for the eventual move, the city held a referendum in October 1960 to approve the $4.2 million needed for the planning and construction of a new central police station. It was narrowly defeated. As a consolation, Taft was given $6,000 to retain architects Libling Michener and Associates, now known as LM Architectural Group, to at least start the planning process.

A political clash between mayor Stephen Juba and premier Duff Roblin scuttled the Broadway city hall deal, and the decision was made to instead build the new city hall on the site of the old one. This shifted the site for the new police station to the west, sharing the block with a proposed multi-storey parkade.

In April 1964, another referendum was held to approve funding for the new police station. This time, it won. What made the project more palatable to voters was the lower price tag of $3.2 million. This was thanks in part to a federal government infrastructure program that would pick up 25 per cent of the construction costs if the building was completed by March 31, 1966.

The vote could not have come soon enough for Taft and his force, as the old police headquarters was condemned in April 1963 after the city’s health department declared it did not meet “minimal acceptable standards” for health and safety.

A daunting task

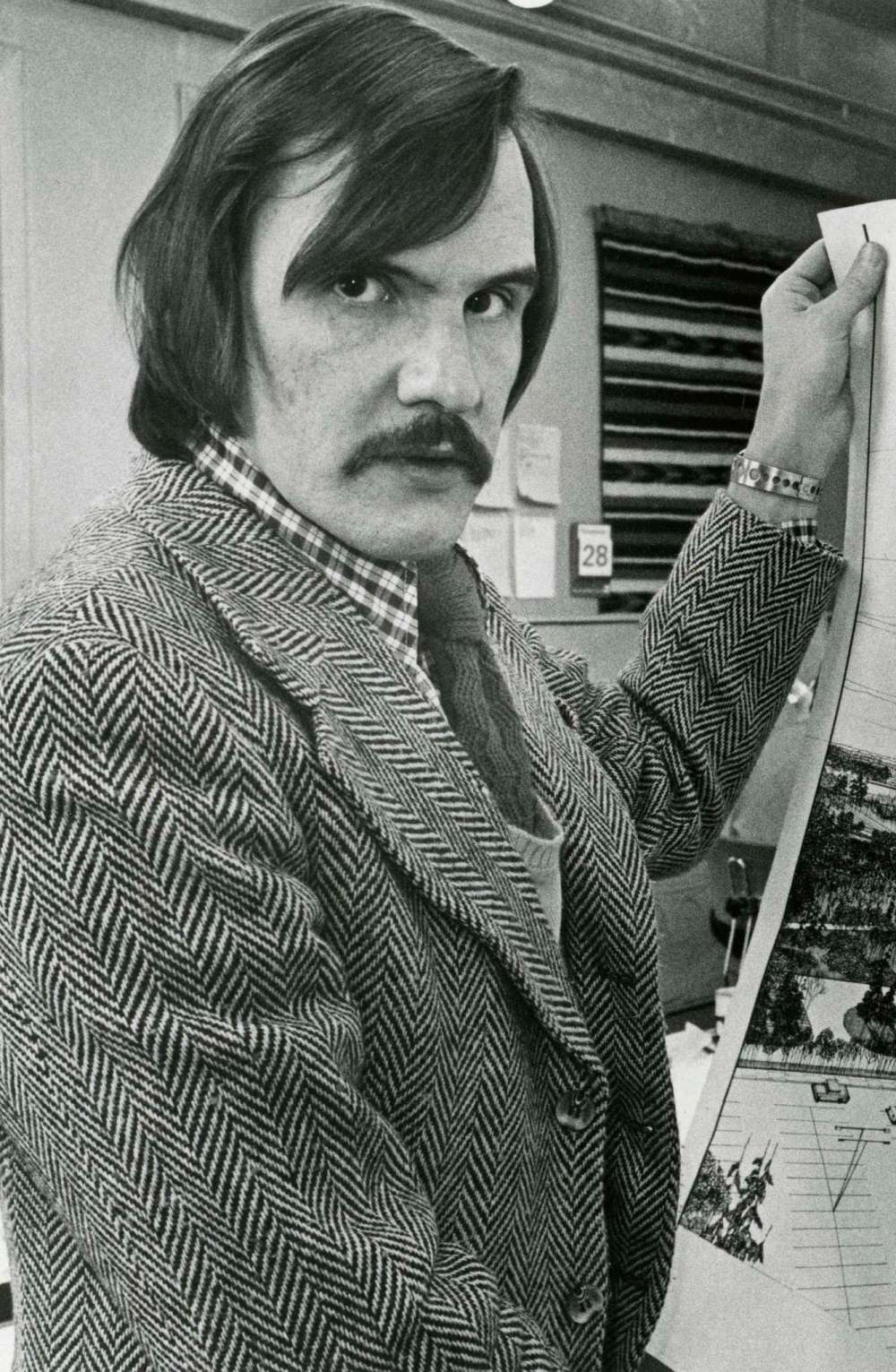

Libling Michener’s lead designer for the project was Les Stechesen, a 1957 graduate of the University of Manitoba’s faculty of architecture. One of his first local projects was the Bridge Drive-In on Jubilee Avenue (1958), but by this point in his career, he had been the lead designer on more substantial buildings such as St. Paul’s High School (1965). He went on to design the Manitoba Teachers’ Society Building (1966), the Leaf Rapids Town Centre (1970) and the Royal Winnipeg Ballet School (1988).

Stechesen had quite the task ahead of him. The new building would not only be home to the city’s police department but also the administrative headquarters for the fire department and the traffic-signal division. Accompanying the men’s and women’s jails were a pair of provincial magistrates’ courthouses and Crown counsel offices. Each department had their own ideas about what size and type of space they needed.

In the end, their competing issues were worked out, and city council gave its blessing to the final design of the Public Safety Building in September 1964.

Construction did not begin until January 1965. This left the contractor, Peter Leitch Construction, with just 15 months to complete the building if the city was going to meet the federal government’s March 31, 1966 funding deadline. In the end, the Public Safety Building came in on time and on budget.

Though today its appearance raises the ire of many Winnipeggers, at the time there was little mention of it in newspaper stories or at city council or committee meetings.

This was likely because the building was seen as just one in a series of modernist structures that had just been completed or were in various stages of development throughout the district. This included the other buildings of the Civic Centre, the Council and Administrative buildings (1962-63) and Civic Parkade (1965) and the Centennial Centre’s Manitoba Theatre Centre (1969-70), Centennial Concert Hall (1967) and Manitoba Museum and Planetarium (1968-70). It was expected others, such as a Metro Winnipeg administration building, would soon join them, but they never did.

To emphasize this variation in modernist styles, Libling Michener were granted a last-minute change to the site plan. They moved the Public Safety Building to the southeast corner of the block instead of directly adjacent to the parkade. This allows for a single view of all of the Civic Centre’s buildings from Main Street.

The six-storey, 117,906-square-foot PSB was initially dubbed the Fortress in some media articles, and that appearance was no accident. The building was to be the headquarters to the city’s protection services, and its strong, stoic facade was meant to reflect that.

The narrow windows and bold mullions, which disappear at the courthouse and jail portions of the third and fourth floor, not only mimicked cell bars, but were also a safety feature. In the social turmoil of the 1960s, police were concerned about snipers shooting into the building from nearby rooftops.

The Public Safety Building had to wait a few weeks for its tenants. The city faced serious flooding in the spring of 1966, and the police department didn’t want to disrupt its officers or the radio dispatch and 999 call centre until the emergency was over.

The police department finally relocated from its Rupert Avenue home on May 5, 1966 between 5 p.m. and midnight. At 6 a.m. the next morning, the prisoners — 35 men and eight women — were transferred in time to have breakfast in their new cells.

‘They wanted to tear the building down’

A plywood-covered walkway has enclosed the sidewalk below the building since 2006 because of the risk posed by its crumbling Tyndall-stone facade.

Earlier this month, councillors on the city’s property and development committee approved an administrative recommendation calling for the PSB to be demolished. The cost of restoring and modernizing the building was determined to be too expensive. The decision will soon go before city council for final approval.

After the committee’s vote, Stechesen told the Free Press he’s devastated by the decision.

“I have the impression this day was predetermined from the start — they wanted to tear the building down,” he said.

Christian Cassidy writes about local history on his blog, West End Dumplings.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.