The fox and the town: Emerson mayor seeks to restore historic barn

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/04/2012 (4908 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

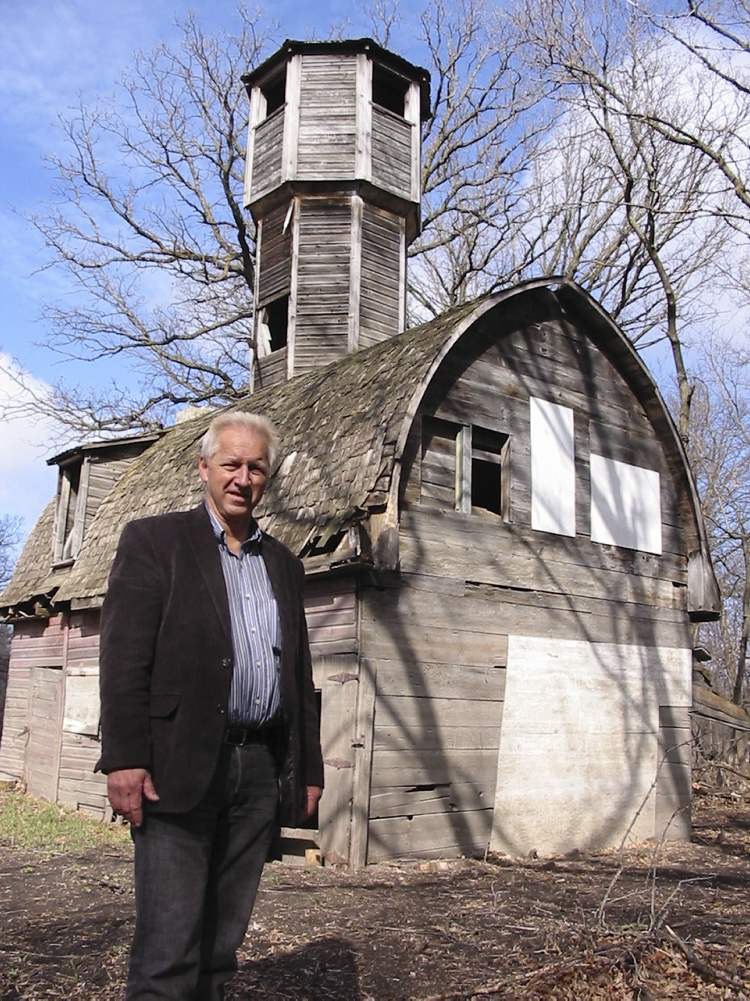

EMERSON — You might say Emerson Mayor Wayne Arseny is crazy like a fox barn when it comes to heritage preservation.

His latest project is restoring a century-old fox-fur barn in this border town steeped in history from its Fort Dufferin days.

Fox barns are hooped barns with those strange towers poking out the middle of their roofs. They have all but disappeared from the Prairie landscape.

The fox-farming craze — its most profitable years were from 1907 to 1921 — was triggered by Paris-led fashion trends in Europe. Fox barns soon spread like Russian thistle across rural Manitoba and fox farming became the most lucrative enterprise on many traditional farms. In the 1920s, farmers could get $300 to $400 per pelt, and breeding stock could sell for up to $1,800 per animal, according to former Manitoban Bob Hainstock in his book, Barns of Western Canada.

The barn in Emerson was built in 1911 “at the height of the domestic fox-fur craze,” said Arseny. As late as 1935, there were still 328 fox farms in Manitoba, said R. H. G. Bonnycastle in an address to the Manitoba Historical Society that year, reprinted in the society’s online archives. In Prince Edward Island, where fox farming began in Canada in 1895, there were 448 fox-fur farms in 1923, says the Fur Institute of Canada website.

And about that strange tower sticking out of the roof? Well, let’s just say the term ‘foxy’ is either a misnomer, or describes behaviour reserved for the privacy of one’s own home, or lair. The canines will not mate if they think someone is watching.

“Fox towers were needed to manage the brief but critical mating period, Hainstock explains. “Farm help had to stay at observation posts (the towers) for days at a time without disturbing the rather bashful animals, but also be ready to move the male to another female pen once he had done his required duty. Today, the whole business is one of drugs and artificial insemination, without the peeping towers.”

Then came the 1930s. The stock market crashed and fashion trends did an about-face. Fox-pelt prices fell below $15. The industry vanished, although not entirely: Fox and mink farming industries today contribute about $115 million annually to the Canadian economy.

“In their day, barns like these were an interesting part of Canada’s landscape,” said Arseny. He doesn’t know of any others in Manitoba, but a fox barn is believed to still exist in Stonewall.

The barn is along the short walking trail that connects the old Fort Dufferin site of 140 years ago with Emerson. Arseny’s research indicates farmers raised red foxes back then, as opposed to the silver fox raised today on farms.

The barn, which has two small cubby holes on each side — similar to cat doors — for the foxes to enter and exit, has a lot of wear. Arseny said Manitoba Historical Resources advised him against restoration. He doesn’t see it.

“If I can still climb up there (to the top of the tower) and look out and wave at you (which he did), that’s solid,” he said.

Some people have already come forward, volunteering various services. JKW Construction in Plum Coulee has offered to remove the turret so the building can be disassembled and repaired. Original material — the lumber was hewn from early sawmills — will be used where possible. Arseny will try to obtain those materials from other abandoned regular barns so the fox barn maintains its weathered look. Arseny expects it will be difficult to replace some of the one-by-18-inch siding.

He plans to begin restoration this summer. He is not looking for government dollars but will do some fundraising and try to enlist volunteers. He has restored heritage houses before, including his own home, which was built in 1882.

He envisions Plexiglas windows, where tourists can look inside and see fox pelts and other artifacts from the period. Someone has already offered the fox pelts. Both red and silver foxes were raised. Arseny hasn’t decided where it should be located.

It’s a small miracle the barn is still standing, considering how many floods it has endured. In the 1997 flood, all that was sticking out of the water was the peeping tower. Normally, a barn like that would lift up but the stone chimney and a century of silt may have weighed it down.

Arseny said it has to be saved before it falls down. “To me, it’s calling us. It’s saying, ‘I’ve lasted this long. Help.’ “

Interested people can email him (at warseny@mymts.net).

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca