Then and now — what’s changed in 25 years

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/09/2013 (4482 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

“A century of paternalism and duplicity in government policies has had disastrous consequences. Canada’s original citizens have lost much of their land and livelihood, family life has been ruptured, and community leadership and cohesion have broken down. These policies have left many aboriginal people not only impoverished, but also dependent and demoralized. These government policies must also be held ultimately responsible for a good portion of the high rates of aboriginal crime, which are the almost inevitable result of social breakdown and poverty.”

— Report of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of Manitoba: The Justice System and Aboriginal People.

KEY INDICATORS

The AJI report produced an exhaustive enumeration of the root causes of crime — the despair, dependency and dislocation born of poverty and cultural collapse. Many of the AJI’s findings still hold true today.

POVERTY — Marginally better

THEN: The AJI report cited 1986 census data that showed the average First Nations person earned $6,100 less per year than the average Manitoban. More than 20 per cent of status Indians reported no income, compared to 11.5 per cent of the total Manitoba population. At the time, Winnipeg’s Social Planning Council reported more than half of all aboriginal households subsisted below the poverty line.

NOW: Measuring poverty is always tricky, and measuring change over a generation is even tougher. It’s safe to say there has been some marginal improvement in aboriginal poverty, but the gap is still huge. In 2006, according to a national report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the median income for aboriginal peoples was still 30 per cent lower than the $27,097 the average Canadian earned. The gap has narrowed a little since 1996, though. A more recent report by the Social Planning Council says that, while the poverty rate of among aboriginal kids in Winnipeg has improved since 1995, more than one in three still live in low-income families.

EDUCATION — Better

THEN: “Aboriginal education has suffered from a long history of being primarily a tool of cultural assimilation,” wrote the AJI commissioners, long before the shameful history of residential schools became widely known. According to the 1986 census, a third of Manitoba’s First Nations population over the age of 15 had less than a Grade 9 education, compared to 18 per cent of the total provincial population.

NOW: Funding for on-reserve schools is still a fraction of what off-reserve children receive, and thousands of teenagers must still leave their reserves to attend high school. But university enrolment rates — the ultimate litmus test — are showing improvement. According to data gathered by Harvey Bostrom, Manitoba’s longtime deputy minister for aboriginal affairs, university enrolment among aboriginal people shot up 77 per cent between 2005 and 2008, and college enrollment by almost as much. And more aboriginal Manitobans are graduating from high school.

UNEMPLOYMENT — Better

THEN: “The Indian unemployment rate is four times the non-Indian rate,” the AJI report said. Back then, more than a quarter of aboriginal people were unemployed, compared to 7.6 per cent overall. “We believe that the actual rate of unemployment among aboriginal people in some communities is two to three times higher than that.”

NOW: According to Bostrom, in the five years leading up to 2005, aboriginal employment increased by 30 per cent. It’s still well below the employment rate among non-aboriginal people, but it’s getting better, primarily in urban areas where half of all First Nations people live.

HEALTH — Marginally better

THEN: The AJI report painted a stark picture of aboriginal health and life expectancy. The premature-death rate for aboriginal people between 25 and 44 years of age was five times higher than the non-aboriginal rate. The suicide rate was more than double.

NOW: First Nations people now have double the premature death rate of all other Manitobans and an eight-year gap in life expectancy. Meanwhile, an extensive study of infant mortality in Manitoba has shown that the death rate for aboriginal babies is more than twice the Canadian average, and study after study points out far higher rates of diabetes, obesity, tuberculosis, heart disease and other ailments.

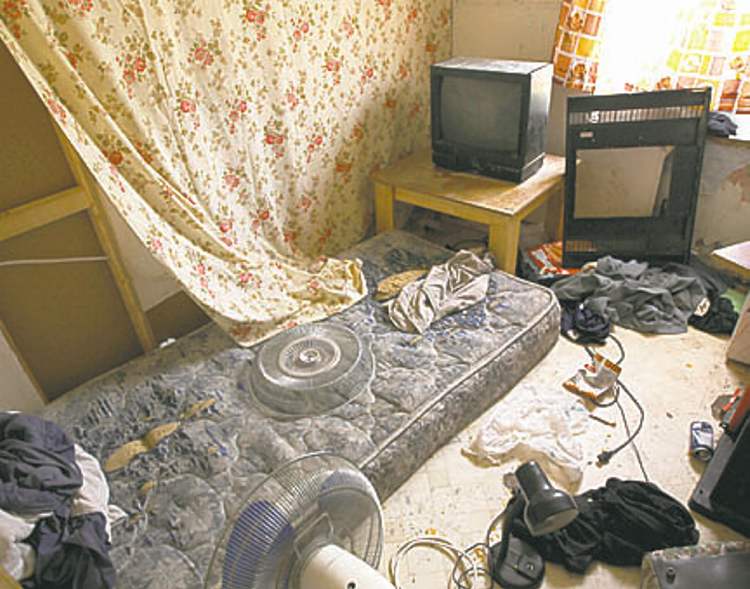

HOUSING — No change

THEN: In the 1980s, on-reserve residents in Manitoba lived in the most crowded and substandard housing conditions in Canada, according to the AJI. Homes were three times more likely to be in need of major repairs, and most lacked central heating and indoor plumbing.

NOW: Most Manitoba reserves are still in a housing crisis. About a quarter need major repairs and nearly two-thirds are over-crowded, according to 2006 census data. Thousands of residents in the Island Lake region alone still lack proper indoor plumbing, remarkable in one of the world’s richest countries.

INCARCERATION — Much worse

THEN: In 1989, in the middle of the AJI hearings, roughly 46 per cent of inmates at the Stony Mountain prison were aboriginal. Inmates at the provincial jail in Headingley made up about 40 per cent of the total population. Incarceration rates among youths were even higher. At the time, the AJI condemned the over-representation of aboriginal people in jails and prisons, calling it “a particularly inappropriate response to the plight of aboriginal people.”

NOW: Manitoba’s jails and prisons are stacked with even more aboriginal people. A 2011 Statistics Canada report said 70 per cent of adults in custody were aboriginal even though only 13 per cent of the total adult population is.

— Mary Agnes Welch