Other means to address the missing

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/03/2014 (4299 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

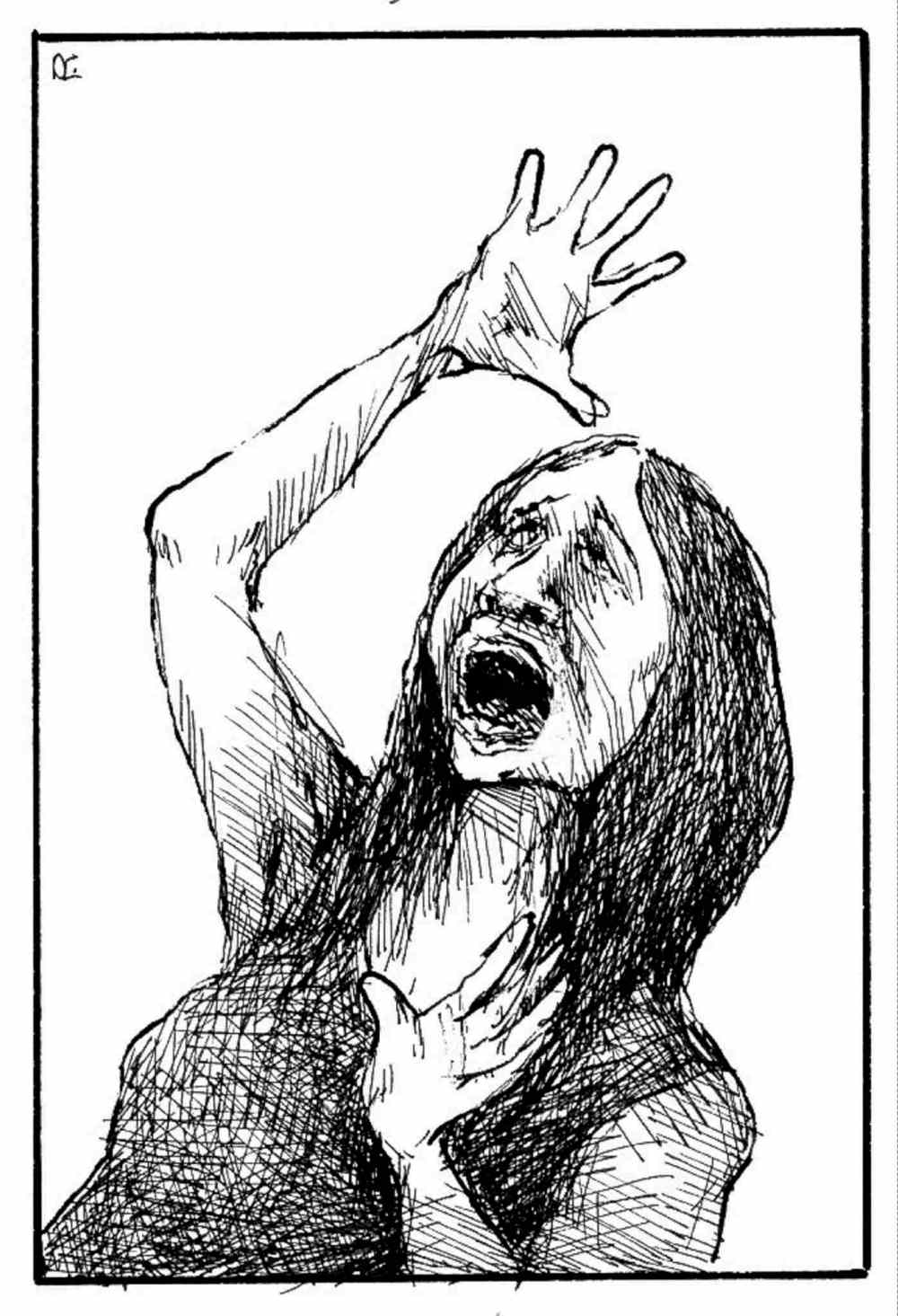

The immediate dismissal of a federal parliamentary committee’s report on Canada’s missing and murdered aboriginal women shortchanges the evidence collected that points to what should be done, now, to protect indigenous girls and women. It begins with money.

Many criticized the Tory-dominated committee for not backing the widespread demand for a national inquiry into the problem. Not everyone agrees — a British Columbia advocacy group and the Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada both said there have been enough studies, and now it is time to attack the factors that lead to heightened risk.

Aboriginal women, disproportionately, grow up in poverty, often in homes of turmoil, and battle racism and systemic discrimination, and many live in communities where violence against women is endemic. They are three times more likely to be the victims of violence generally and far more likely to be targeted by strangers, trafficked or murdered.

Further, the committee accepted the accounts it heard that police continue to dismiss relatives’ calls for help out of the belief the woman was just looking for a fix, was doing what she usually does and would turn up eventually. This, despite families telling them that such behaviour was out of character.

The Harper government rightly is refusing the demand of advocacy groups and many provinces for a national inquiry. It should heed, however, the consensus that what aboriginal communities need is adequate funding to areas that can protect women, keeping them from risk — schools, robust preventive child-welfare programs, adequate women’s shelters, second-stage housing on reserves and Inuit communities, and programs in communities where violence is endemic. The problem was described in stark numbers: There are 633 First Nations communities and only 44 shelters across Canada.

Attorneys general must act on accounts that police continue to downplay reports of missing women. An audit of cases could reveal whether and why delays in investigations exist. The fact that aboriginal women, especially those involved in the sex trade, are at heightened risk should speak to speedier, not delayed, action when they go missing.