Titanic teaches vigilance

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/04/2012 (4936 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

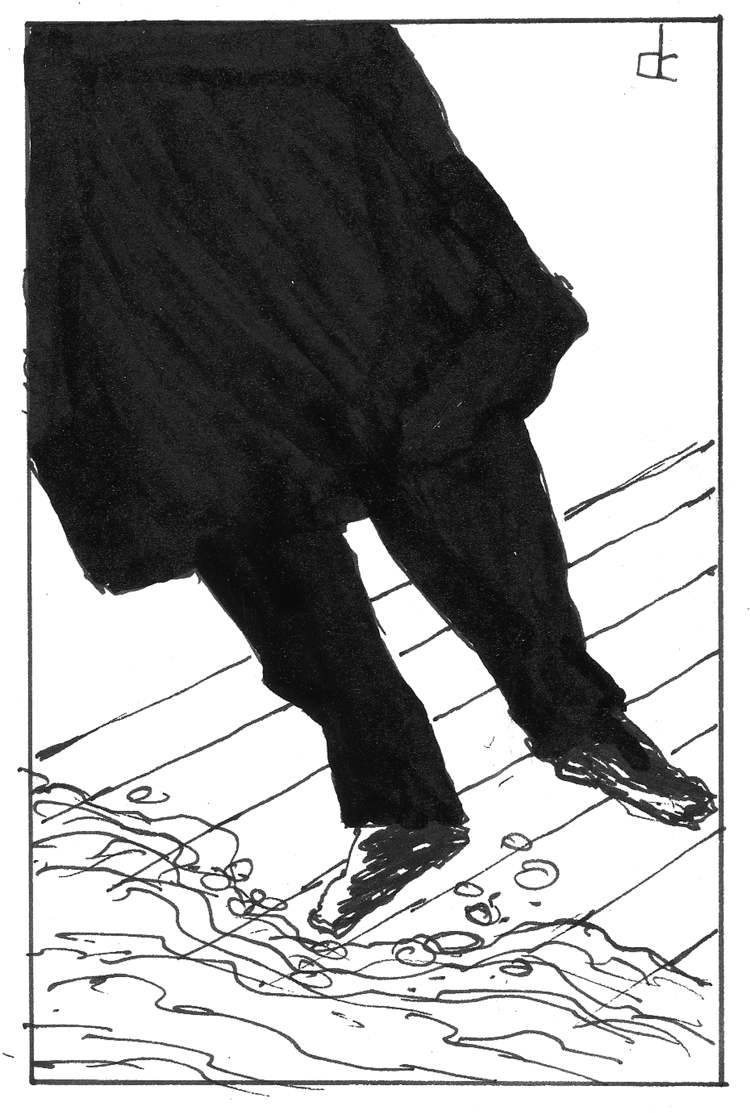

In January 1945, a converted German hospital ship, the Wilhelm Gustloff, was sunk by Russian torpedoes in the Baltic Sea, killing more than 9,000 people, most of them civilians, including 4,000 children. It is the greatest seagoing disaster in history. The worst maritime disaster in Canadian history happened in 1914 when the Empress of Ireland collided with another ship and sank in the St. Lawrence, with more than 1,000 lost.

And yet, when the subject of ocean disasters is raised, it’s the Titanic that towers above them all. The catastrophe has spawned an encyclopedia of metaphors for wilful blindness in the face of disaster, avoidable catastrophe, incredible stupidity, hubris and a range of other superlatives that worked their way into the English lexicon over the last 100 years.

Movie director James Cameron has even called it a metaphor for the end of the human race caused by global warming. Apparently the human race is heading toward disaster by ignoring the warning signs about climate, much the way the Titanic’s captain disregarded numerous reports the ship was heading toward a massive icefield.

As evidenced by the proliferation of TV documentaries, books and exhibitions on the 100th anniversary of the sinking, the Titanic is truly unsinkable in terms of its impact on the imagination and the quest for an enduring meaning.

The sinking affected people around the world, including in Manitoba. Some 30 passengers had a Manitoba connection, according to author Michael Dupuis. Other sources say at least 22 of them died along with 1,500 others that frigid night in the North Atlantic. The city went into mourning for all the victims, with special church services and fundraisers to help orphans and widows.

The White Star Line, owner of the Titanic, had an office in a building at 333 Main St., adjacent to the Bank of Montreal building. The building’s windows featured the Titanic in various stages of construction, evidence of the worldwide interest in the project. When the building was demolished in 1980, there wasn’t a peep about its link to the disaster.

Five years later, the wreck was discovered at the bottom of the Atlantic, and the story surfaced once again.

While there have been greater disasters since the Titanic, the ship’s brief life had all the elements of a great novel. It was the greatest, largest, fastest and most luxurious ship of its time, an unsinkable leviathan, as its owners boasted. The ship’s manifest was a microcosm of the contemporary class structure and a reflection of the great disparity in wealth and status between the poor and the rich. The poor also died in the disaster at a higher rate than the wealthy. It was an epic disaster transmitted around the world via the new technology of wireless telegraph.

The central lessons of the Titanic remain relevant today. It’s about risk, and how much of it scientists, explorers, government and society are prepared to accept in the pursuit of more knowledge, convenience and scientific achievement.

As Mr. Cameron stated at a NASA symposium: “Titanic teaches us to be constantly vigilant, to assume nothing about our methodology, to constantly ask the question, ‘What are we doing wrong right now?’ “

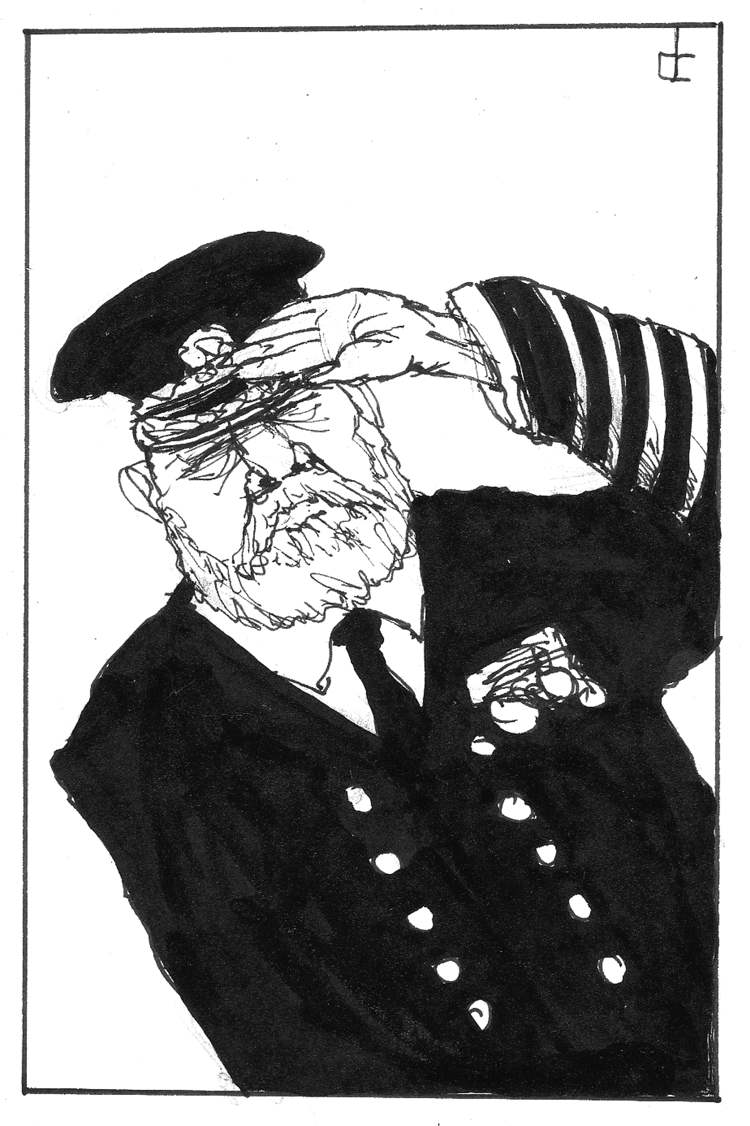

He noted the Titanic’s captain was criticized for steaming at full speed into a icefield, but that’s the way ships had always operated because they had the ability to slow down and turn quickly. The Titanic, however, was much larger than any other ship afloat, and its designers failed to ask whether the old practices followed by smaller ships would work.

It was hubris of a sort, but more important, it was a failure to constantly re-evaluate our methods and our knowledge to ensure they are valid. It’s the kind of mistake that has been repeated numerous times since the Titanic met its end. One hundred years later, the lessons of eternal vigilance and humility remain as valid as ever.