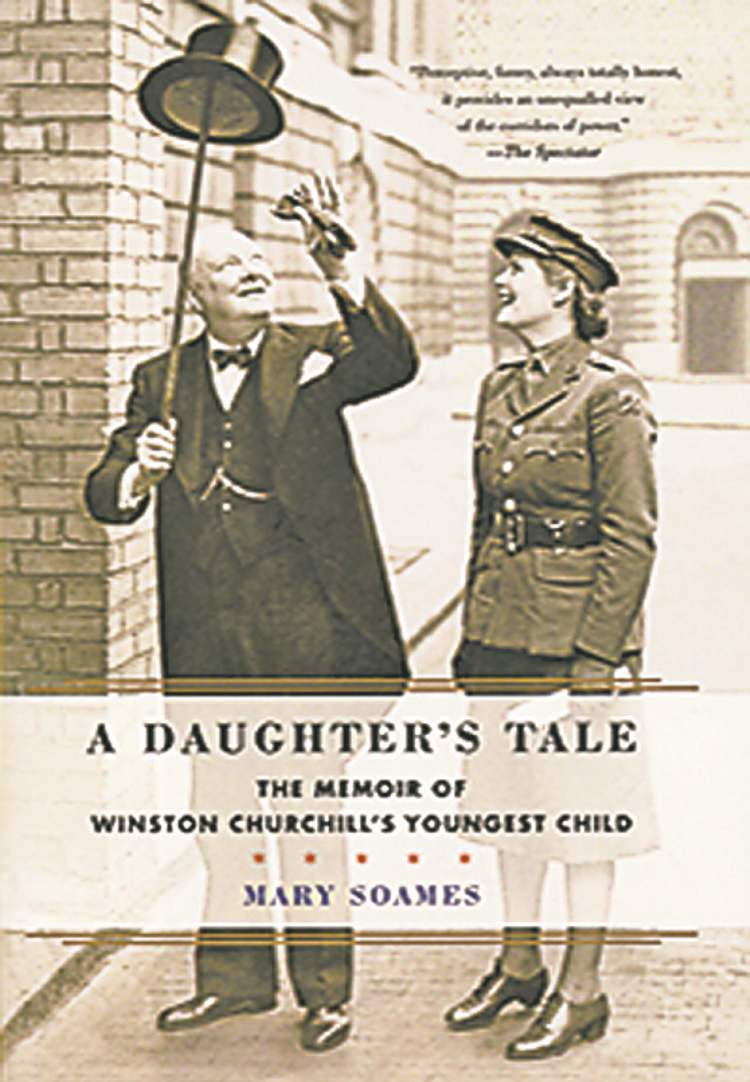

A look at wartime through the eyes of Churchill’s daughter

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/08/2012 (4800 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

THIS memoir should come with a tea cosy.

At 89, Mary Soames is the youngest and last surviving child of British prime minister Winston Churchill and his wife Clementine. Soames has made extensive use of diaries, research and her circle of friends and influence to give a detailed account of her Second World War experiences. That includes the civilian and the military.

Soames was only 17 when war was declared in September 1939, while her father, soon to be elected PM, was 64. His career was seemingly over, and his speeches against appeasement and in favour of Britain re-arming had been met with either stony silence or outright hostility.

She offers a loving and pugnacious daughter’s perspective on the great man and his battles, with never a hint of doubt.

Keeping in mind her youth at the time, she expresses her emotions without reservation.

The early part of the book describes home life before the war, including the purchase of the family home Chartwell, which Churchill acquired in 1922 on a whim. This was done without consulting his wife, Clementine, and produced a rare tiff.

Even now a visit gives a feel of Churchill at ease, what with some brickwork he did himself and rooms that leave the visitor with the feeling that he has just stepped out. Soames’ book produces the same feeling.

Considering her position of privilege, Soames comes across as young for her years. But accompanying her father on some of his political rounds and the coming of the war provided her with an early maturity in some respects.

As to affairs of the heart, she seems to have had a crush on someone new every few weeks. She’s quite willing to provide the diary entries to describe the swooning and mooning.

Viewers of Downton Abbey won’t be disappointed. She describes the customs, costumes and comestibles of the 1930s and ’40s in some detail befitting a young lady of fashion. As well, she name drops something fierce, although to be fair, there’s usually a good reason to mention someone, and those not up on their Debrett’s will find footnotes to help identify the nobs.

War may have been expected in the Churchill family, but Soames provides a unique view of the shock and dismay upon its outbreak. She recounts the early phoney war, then the growing awareness of the seriousness of what was to come, followed by the London Blitz, the advent of the V1 flying bomb and then the V2 rocket attacks.

We see an aging Churchill in full war mode, but from his daughter’s perspective — not one often presented, and this includes his defeat of the black dog of depression (if only temporarily) — by showing him at home.

“Papa in excellent form,” she quotes from her diary, “sang Poultry and Half a Woman & Half a Tree.”

Balancing the war news is Soames’ description of the almost desperate attempts by young people to be just that — young.

She recalls the parties, going to the theatre and the outings, suggesting that even rationing couldn’t stop them from having a “knees up” (or the upper-crust equivalent).

It is a narrow social history, but A Daughter’s Tale offers an entertaining (if overlong) feel for the time and place and the waves of optimism and despair that came with each newscast or loss of a young friend.

Soames’ war service in a mixed anti-aircraft battery both in England and on the continent gives her the credentials to tell her tale.

Ron Robinson is a Winnipeg broadcaster who keeps a Karsh-like tiny bust of Winston Churchill on his mantle.