Work explores relationships between violence, masculinity, sport and show business

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/04/2013 (4670 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Our culture tolerates and even champions male aggression, up to and including physical violence. We relish hockey fights, honour war heroes, and celebrate general pugnacity in everything from the meat-headed, spandex-clad pageantry of pro wrestling to the cutthroat tactics of politicians and businessmen.

The glorification of bellicosity doesn’t, for the most part, extend to bellicose women, however, and in practice it only applies to certain men some of the time. Race and class largely determine which dudes are encouraged to clobber which other dudes, when, and for whose benefit or entertainment, but the ability and willingness to knock the stuffing out of an opponent remains, for many people, central to what it means to “be a man” (if by “man,” I suppose, you mean “prehistoric imbecile”).

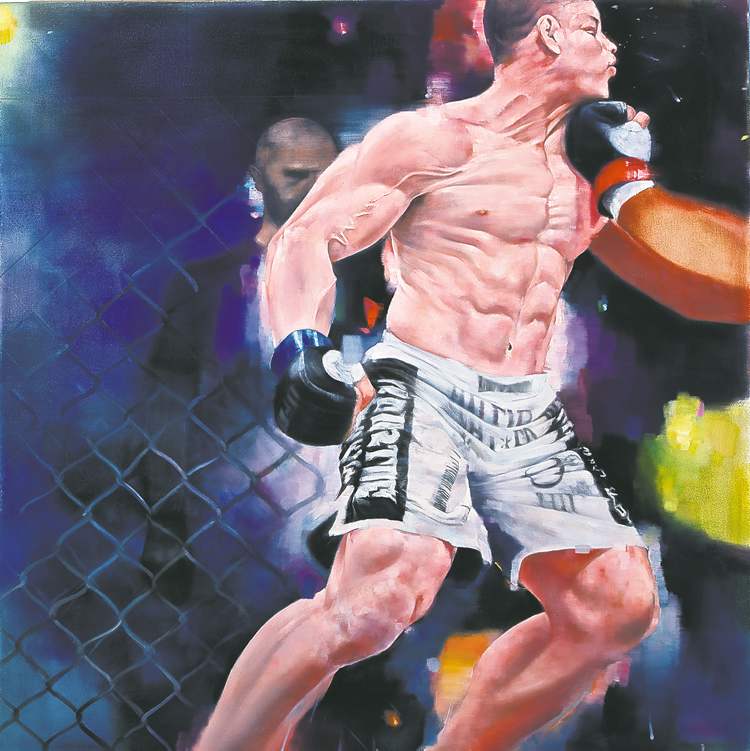

Fight, Tom Lovatt’s current show at Gurevich Fine Art, investigates how this perceived link between masculinity and violence plays out in sporting arenas and on television screens. His traditionally-minded depictions of brawling boxers and mixed martial artists, large-scale oil paintings and intimate drawing studies, echo a collective fascination with ritualized hostility and its powerful association with gender identity, inviting consideration and critique.

Lovatt maintains an ambivalent stance, neither flinching from his subject matter’s disturbing intensity nor denying its spectacular, even seductive appeal, and what viewers take away from the work will largely reflect their existing views and sensibilities. The paintings depict actual matches between historical and contemporary fighters, so a familiarity with combat sports likely adds a layer of interest in this respect. (Coming to the show, I was dimly aware of the career-ending 1951 match between Rocky Marciano and an aging Joe Louis featured in Lovatt’s Do or Die but wasn’t familiar, for instance, with Wanderlei “The Axe Murderer” Silva).

The works frequently reference art history, too. Lovatt clearly aspires to the gritty dynamism of early 20th-century American realist George Bellows’s own boxing pictures, but while Lovatt’s preferred palette skews unexpectedly toward saturated hues and seasick pastels, lending these familiar images a lurid, television-ready sheen, the occasional anatomical issue and a tendency to overwork leave some of them a bit stiff. Bellows also depicted noteworthy real-world fights and fighters, and, like Bellows, Lovatt highlights the jeering faces of spectators who serve as visible reminders of our own complicity in the scenes.

An image of UFC’s Chael Sonnen and Nate Marquardt grappling on the mat overwhelmingly echoes the “Uffizi Wrestlers,” a famous copy of a third-century BC Greek sculpture of a virtually identical scene. In recalling that classical celebration of male beauty, Lovatt touches the issues of submission and homoeroticism that complicate so many displays of male aggression, themes that arguably re-emerge in his series of small, highly realized sketches. Made with sanguine conté (a type of brittle, reddish-brown crayon with a look similar to coloured pencil), the drawings have a delicate quality at radical odds with their brutal imagery, while open, “unfinished” passages and overlapping figures help create a sense of movement and choreographed commotion that the paintings sometimes lack.

Fight may not break new ground as such, but whether one’s inclined to see the images as barbarism or beefcake (or “images of strength and athletic prowess,” I guess), they provide a worthwhile opportunity to reflect on the interrelatedness of violence, spectatorship, gender, and identity. Now pass the peanuts.

Steven Leyden Cochrane is a Winnipeg-based artist, writer and educator who will never understand the appeal of boxing.