Large exodus of front-benchers highly unique

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/11/2014 (4077 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

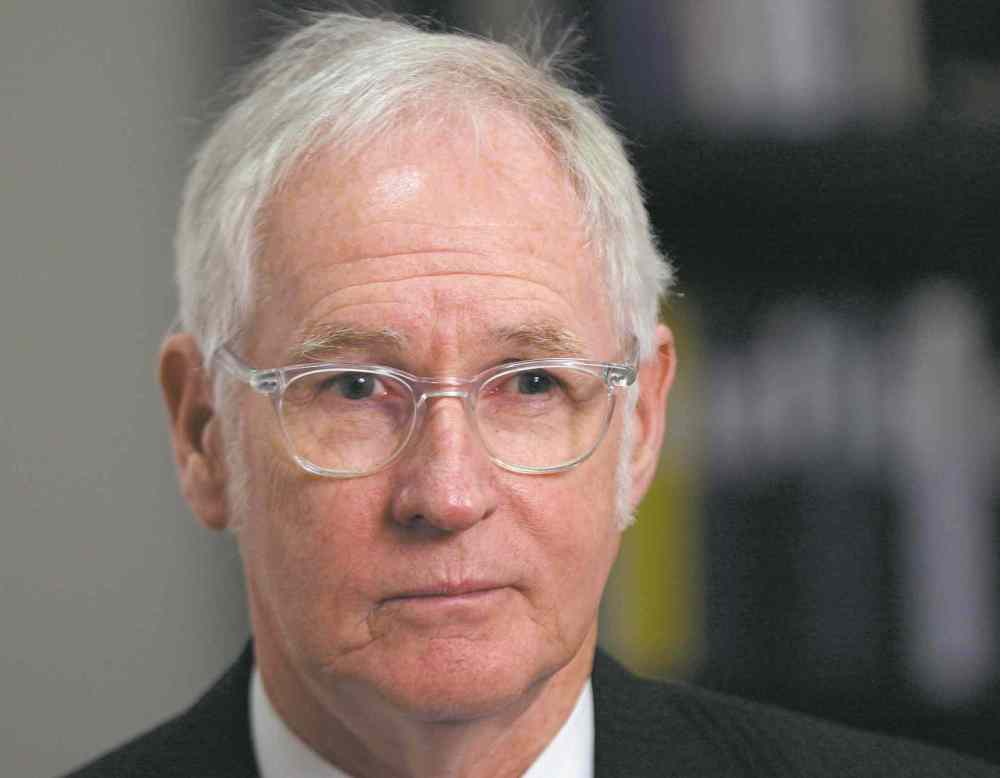

MANITOBA’S messy caucus revolt is unique in English Canadian parliamentary history, at least in the last 118 years. Not since 1896 has a first minister been buffeted by the resignation of nearly his entire front bench, which is what happened to Premier Greg Selinger Monday after more than a week of internal turmoil.

Most caucus revolts are mild in comparison, but few leaders survive even the small ones. Former Liberal prime minister Jean Chrétien finally succumbed to long-standing internal rivalries, and premiers such as Alberta’s Alison Redford stepped down before a full-fledged coup could occur. The revolt in the senior ranks of Manitoba’s NDP appears far more crippling.

Caucus uprisings, especially public ones, are rare to begin with. University of Toronto political scientist Graham White has written Canadian premiers and prime ministers are “all but impervious to cabinet or caucus revolts,” largely because party leaders are chosen by party members, not by MLAs or MPs. In Selinger’s case, only party members can force him out, and it’s still not clear how, when or even if that might happen. Until then, the only recourse for unhappy NDP MLAs is a non-confidence vote, a catastrophic step that would require at least nine New Democrats to vote against their own government.

As we get used to this stalemate, here are five (relatively small) caucus revolts to consider.

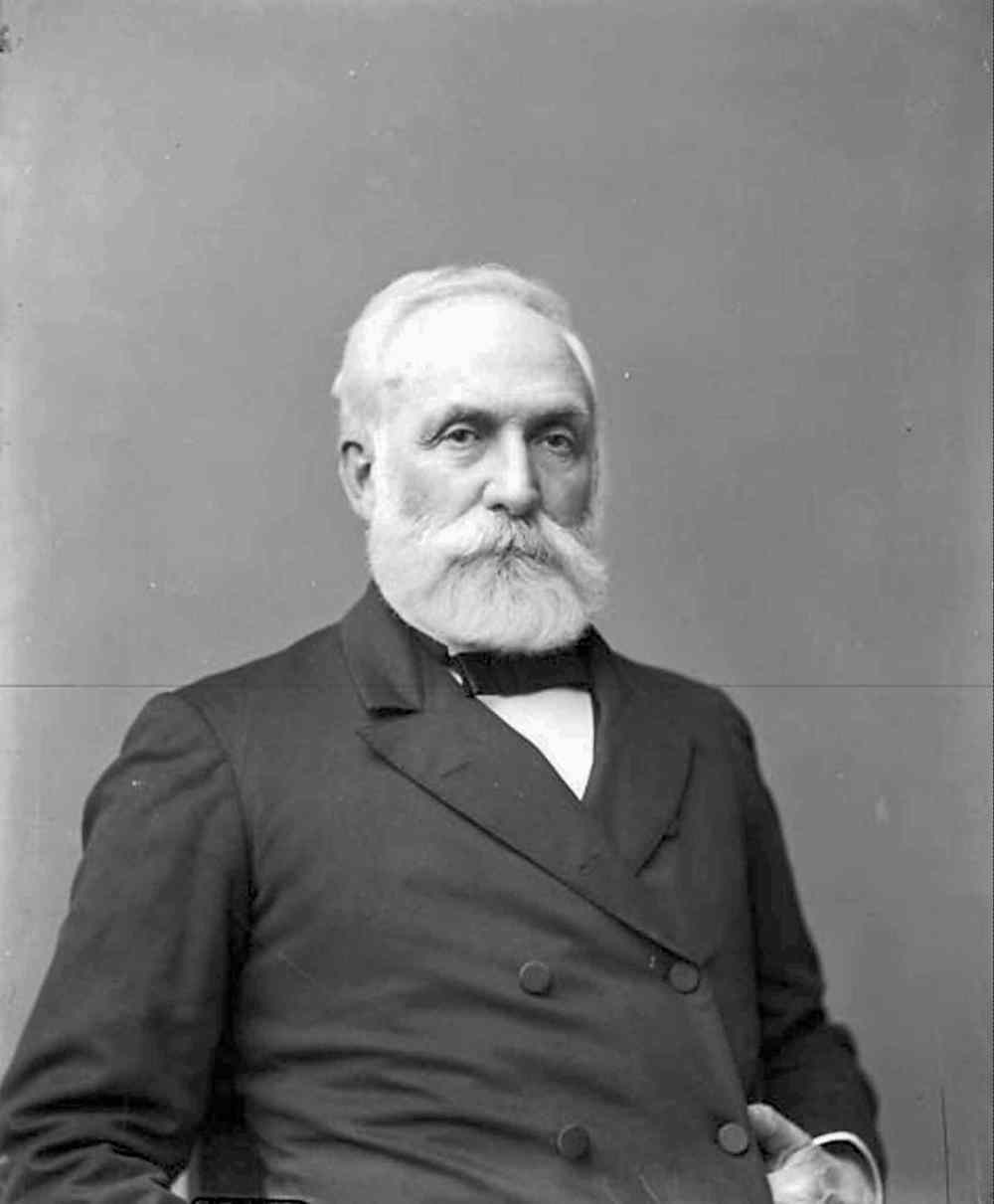

Prime Minister Mackenzie Bowell

You’d be forgiven if you’ve never heard of him. He was Canada’s fifth prime minister, serving for two years in the mid-1890s. He struggled with the Manitoba Schools Question and was seen as a mediocre leader, a compromise candidate who lacked a firm hand. One biographer noted his reputation for “evasion, weakness, unreliability and fatuity.” In January 1896, half of Bowell’s Conservative cabinet, seven ministers, resigned en masse and asked the governor general to replace Bowell as prime minister. That sparked several months of political confusion before Bowell finally resigned in April 1896.

Alberta Premier Alison Redford

After months of scandal over exorbitant travel and personal expenses, Redford stepped down in March after just two years as premier. Even Redford, by then one of the least popular premiers in the country, didn’t fall victim to the mass resignation of senior cabinet members. In fact, in the days before her resignation, only one backbench MLA and one junior minister resigned in protest, though several others were considering leaving caucus. Redford’s resignation came about largely due to pressure from party officials.

Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Kathy Dunderdale

Like Selinger, Dunderdale took over her party’s helm from a wildly popular premier, Danny Williams. She lasted three years as premier, weathering one defection, poor polling figures and then growing criticism of her handling of power outages and rolling blackouts in early January. In the days before her Jan. 22 resignation, her former caucus chair crossed the floor to join the Liberals. But her departure was seen as largely voluntary, a pre-emptive move that wasn’t precipitated by days or weeks of public sniping.

Quebec Premier René Lévesque

In the lead-up to the provincial election following his failed 1980 referendum, the combative separatist leader of the Parti Québécois was accused of abandoning Quebec’s independence in favour of new constitutional talks with then-prime minister Brian Mulroney. Ten backbenchers and ministers resigned in protest, but Lévesque survived a leadership review in January 1985. Weakened and tired, he resigned less than six months later.

Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chrétien

Chrétien managed to fend off for some months intense pressure to resign by former finance minister Paul Martin and his supporters. The feud consumed much of 2002. When Martin left cabinet, he began openly organizing a leadership bid. By August, less than half of Chrétien’s caucus signed a letter supporting him in an upcoming leadership review and Chrétien announced he would step down in 2004, a date he later moved up. It was among the most divisive political street fights in Canadian politics, but even then there was no mass resignation of caucus or cabinet members.

Manitoba Conservative Leader Stuart Murray

Though not a first minister, Murray resigned as Tory leader following a caucus revolt in 2005. Interestingly, much like the current NDP revolt, the Tory mutiny was led by women in caucus, such as Mavis Taillieu, Bonnie Mitchelson and Myrna Driedger. Some were demoted from shadow cabinet for speaking out in favour of a leadership review. At the party’s annual convention, only 55 per cent of delegates voted against a motion, seconded by Taillieu, to review Murray’s leadership, a lukewarm endorsement Murray said was not enough to continue.

— Mary Agnes Welch