Unspeakable cruelty

Eisen's Auschwitz recollections difficult but necessary read

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/04/2016 (3475 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s easy for many of us to take the freedoms we enjoy — our comfortable homes, our livelihoods, routines, belongings, and even our very lives — for granted.

It’s incomprehensible for most of us to imagine being suddenly stripped of not just all these things but of all rights, to be deprived of food, water, and clothing, to be robbed of all human dignity and to have our lives and the lives of our family members regarded as utterly valueless — something only fit for extermination, murder or massacre.

But it happened — and not all that long ago — at Auschwitz and the many other death camps systematically built by the Nazis during the Second World War.

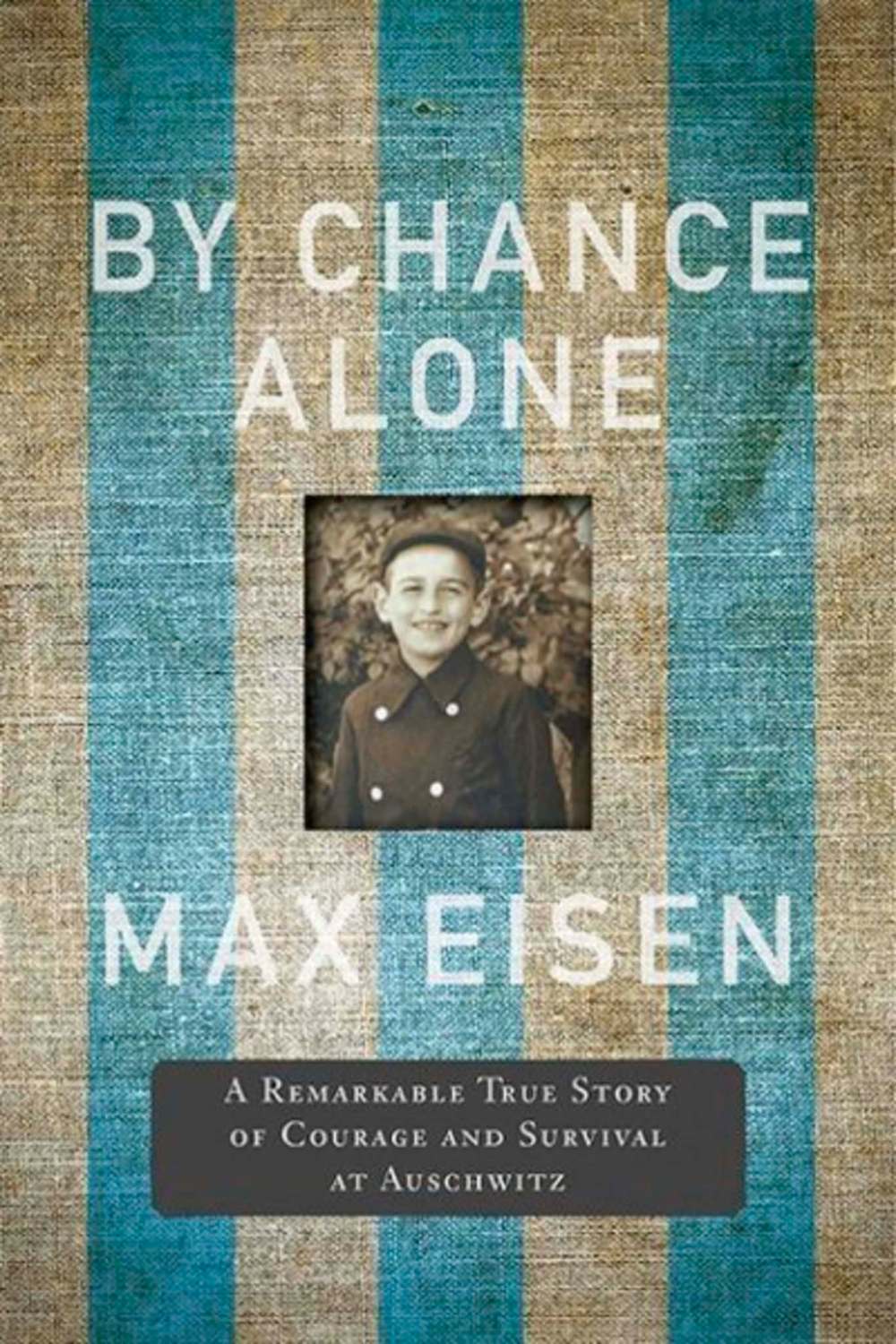

Max Eisen’s gripping memoir of his life before and after being deported to Auschwitz at age 15 is almost unbearable to read — so painful, it should be read in small doses.

But it’s an absolutely necessary, important read — even a crucial one. How much more horrifying would it have been to have lived that life than to simply read about it? To even write about it is an act of immense courage.

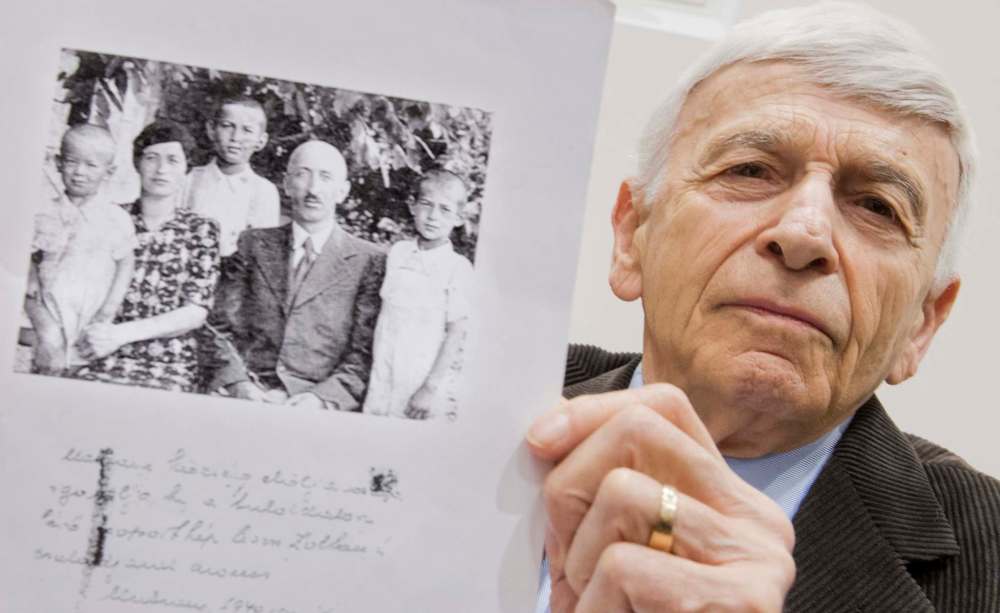

Eisen, who lives in Toronto, struggled to write about his experiences for years, even though he was a passionate Holocaust educator for decades, speaking at schools, universities and communities across Canada. Finally and painstakingly putting pencil to paper, Eisen committed at long last in his 80s to recording this heartbreaking story of loss, endurance and survival.

He wrote not just “to honour and remember the people and human potential that was lost” — it was also to honour a promise he made to his father, whose last words to young Max were: “If you survive, you must tell the world what happened here.”

It’s a story that has been told before, of course, but it bears repeating — requires it, demands it — because, as Eisen warns in his epilogue, people must always be careful “to prevent hate from disrupting, distorting and endangering our societies. We must all be alert to the dangers of hatred, speak out against discrimination, and defend the fairness and openness of a free and democratic society with rules of law to sustain it.”

Eisen tells the story of his life from his childhood in a small town in the former Czechoslovakia to his entire family’s deportation to Auschwitz in Poland.

He describes the insane brutality of the death camp, the daily horrors he endured there and finally writes of his long, achingly slow journey to freedom and eventual healing.

Born in 1929 in Moldava, Czechoslovakia, Eisen describes what seemed like an almost idyllic childhood.

He had both non-Jewish and Jewish friends, and lived in a large dwelling with a close-knit, loving family that included younger siblings, parents, grandparents, and an uncle and aunt.

The family made fruit preserves from their own orchard and raised their own grain-fed chickens and ducks on a spacious property. They were well-educated and prosperous. Young Max and his friends often gathered there to play cowboys and bandits.

But it was not to last. In 1939, Eisen says, “German troops crossed the Czechoslovakian border and took control of Prague. Czechoslovakia ceased to exist and the country was partitioned into three regions.”

After gradually having most of their rights taken away from them, Eisen’s family was deported to Auschwitz in the spring of 1944. He describes how every day brought certain death and new horrors at the hands of the Nazis.

His story is written in a manner that makes it difficult to put the book down. He pulls the reader into the story and holds them there until the final page has mercifully been turned. The prose is straightforward, utterly simple, sincere and completely absorbing.

Likely the result of Eisen’s decades speaking to students, By Chance Alone is written in such a way that anyone from high school age and up will comprehend. He has said all of his royalties will be going to charities “that promote education and humane causes.”

Eisen tells readers that today, “with anti-Semitism on the rise — and so blatantly expressed in contemporary Europe,” we need to be ever-alert to “an understanding of how evil can operate when it remains unchecked.”

Yes, it’s easy to take our lives and our freedoms for granted. But Max Eisen’s amazingly courageous and incredible memoir serves as an excellent reminder to never do so again.

Cheryl Girard is a Winnipeg writer.