Message received

Taylor's indigenous sci-fi stories tackle hard truths

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/10/2016 (3368 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Much has happened in the fictional central Ontario Anishnawbe (Ojibway) community of Otter Lake over the years that it has served as a home base for the imagination of Canadian writer, playwright and journalist Drew Hayden Taylor. For the first time, however, aliens, super-human beings, sentient robots and government mind control have descended upon the peaceful town.

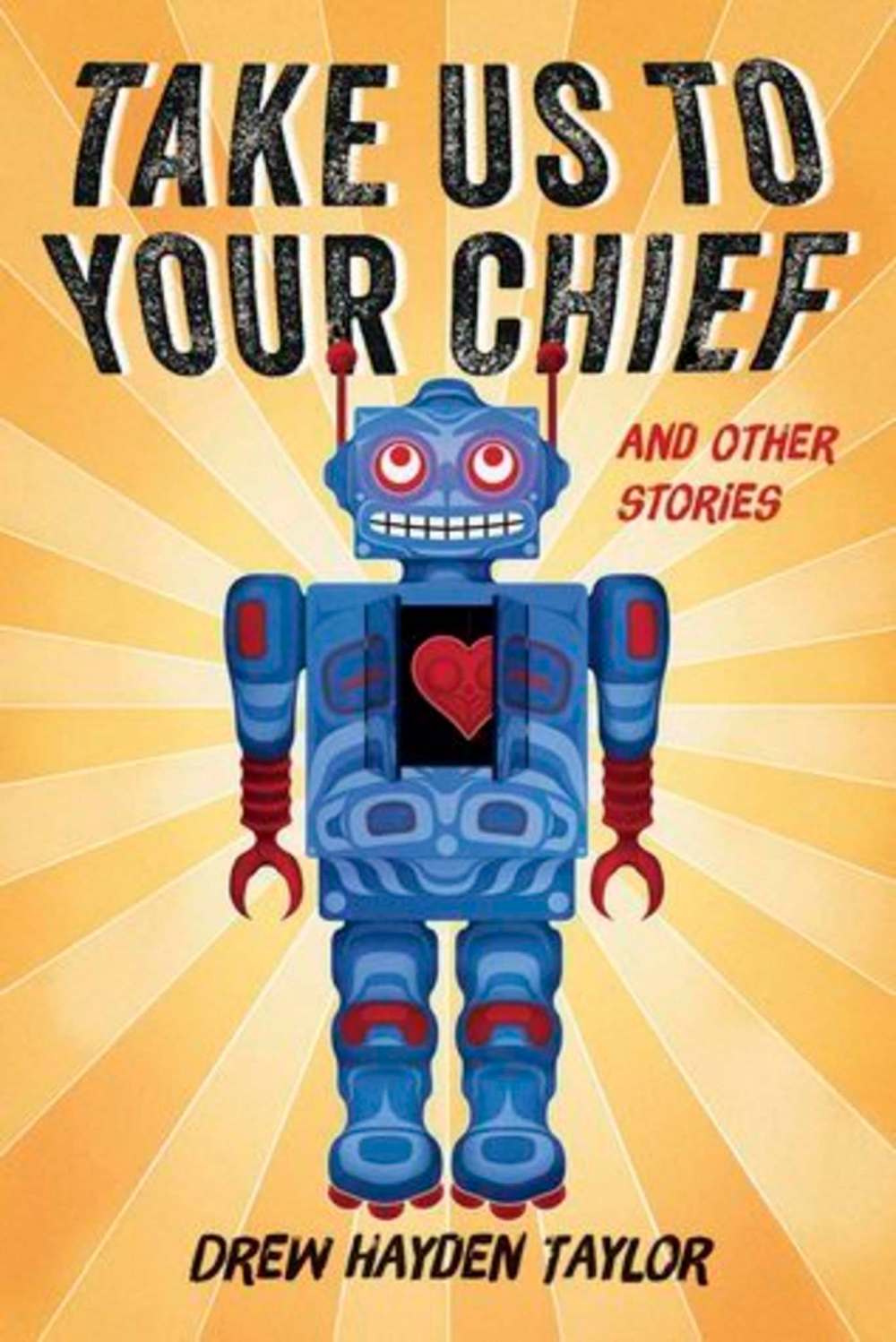

In Take Us to Your Chief, Taylor (author of Dead White Writer on the Floor and Funny, You Don’t Look Like One: Observations from a Blue-Eyed Ojibway) indulges his love of classic science fiction filtered through an aboriginal lens. Avenging aliens summoned to Earth by radio waves broadcasting ancient recordings of traditional songs wipe out most life on the planet in A Culturally Inappropriate Armageddon. A half-Ojibway astronaut remembers his Otter Lake-born grandfather while traversing the universe to mine valuable minerals in Lost in Space. A journalist for the Otter Lake newspaper runs for her life when she discovers the nefarious plot of a secret government department to keep Canada’s indigenous peoples subdued using mind control through high-tech dream catchers in Dreams of Doom.

Beyond being purely personal writing and “a labour of fun” for Taylor, he has found a brilliant way to spotlight the true dystopian condition of Canada’s First Nations people through classic themes first used by Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, and even Stan Lee, with his superheroes born either on other planets or in freak accidents involving toxic chemicals.

Case in point is Superdisappointed, where Kyle Muncy struggles daily with the complications of being a superhero: his super-sensitive sight and hearing make it hard to get a good night’s sleep; he could fly but chooses to hitchhike to town for fear of accidentally damaging property or killing livestock in the way; his skin is impenetrable and his strength superhuman, causing his boyfriend to break up with him. His doctor speculates toxic chemicals are to blame. Agricultural runoff flowing into Otter Lake’s drinking water, high levels of undetected radon gas, plus the black mould in Kyle’s house turn him into the first aboriginal superhero. Given that these problems persist in real life on many reserves in Canada, Taylor’s wry speculative twist on a despicable situation turns tragic into strangely empowered.

Occasionally, Taylor chooses a darker tone. With reflective Bradbury-esque melancholy, Taylor presents the truth of the human condition through the perspective of a newly-awakened artificial intelligence. In I Am…Am I, researchers feed information about human life and history to a computer program that has taken on a life of its own. Quickly, it aligns with aboriginal spirituality, explaining to the bewildered lab-coated humans that “Many Aboriginal cultures believe that all things are alive…. They would believe that I have a spirit. That is comforting.” Upon learning about the extinction of many indigenous cultures owing to colonization, however, the computer brain becomes inconsolable and chooses a similar fate for itself.

Strangely, Taylor apologizes in the book’s foreword for juxtaposing what he thinks is an unheard of combination of literary genres to create “Native Science Fiction,” but he shouldn’t have to. He tries to pin it on personal reasons: “I’m half Ojibway and half…not. Combining genres of writing is a favourite hobby of mine.”

But with a recognized need for change in the perception of Canada’s indigenous peoples, literature like this is timely, needed and logical.

Christine Mazur holds a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Manitoba. In an odd juxtaposition, her science-fiction graduate seminar was taught by a Milton professor: truth can be stranger than fiction.