Spine assessment clinic cuts wait times

Innovative model touted as a way to decrease lines for other specialty services

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/01/2018 (2860 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The wait-list for a Manitoba spine assessment has dropped from “forever” to under six months in two yellow clinic rooms tucked down a first-floor hallway at Health Sciences Centre.

The nearly empty, nondescript rooms are part of what Dr. Michael Johnson likes best about the provincial spine assessment program, which started as a trial in May 2015 and is now being touted as a model to cut wait times for specialty services like MRIs across the province.

“There’s no $25-million machine,” he said.

“Instead of chucking money at the problem, we threw a high expertise group of people at it: good, old-fashioned medicine, face-to-face conversation, good physical exams and very thorough histories.”

The spine surgeon wait-list was nearing 5,000 people in 2014, binders and binders full of patients — some of whose files had been accumulating since 2002 — awaiting assessment.

To be a non-urgent patient on that list was practically a guarantee that you’d be waiting endlessly (there are only five full-time spine surgeons in the province).

If the system hadn’t changed, Johnson said, “You’d still be waiting.”

To make matters worse, the vast majority of those on the list aren’t even good candidates for the surgery, meaning they’d wait years to be assessed and told, “sorry, go back to your family doctor.”

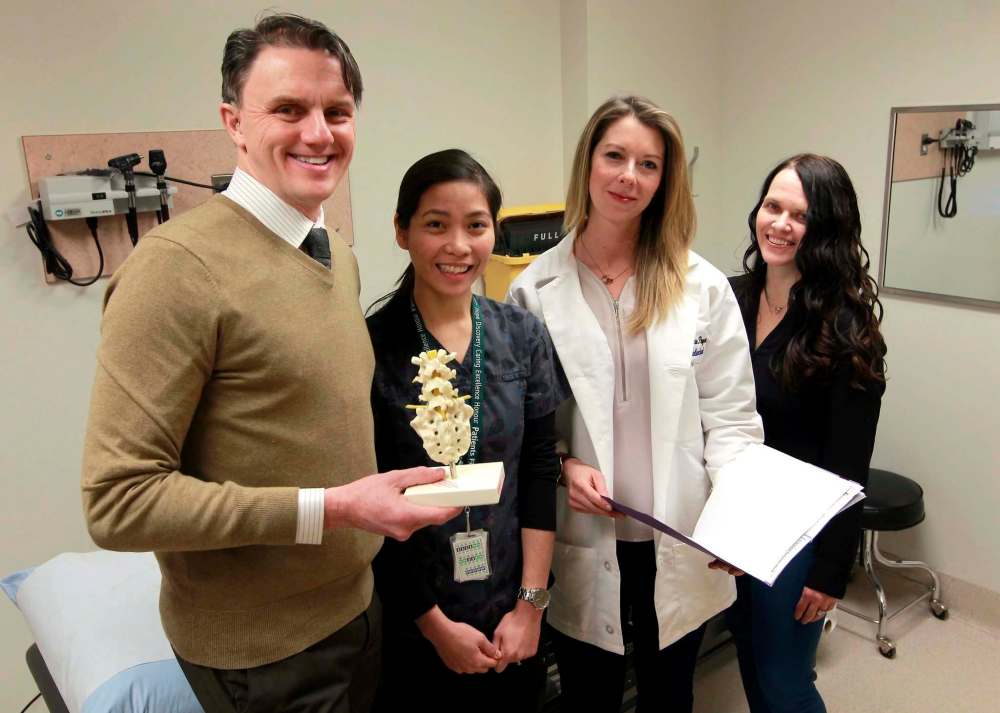

That’s where Karen Malenchak and Shelley Sargent come in.

The two physiotherapists both work part-time in the Spine Assessment Clinic, serving as “surrogate assessors” for Johnson and his fellow surgeons, handling the referrals from doctors for patients with back pain that the doctors can’t treat.

Both women already knew how to conduct the physical examinations, they just needed practice at identifying what type of back pain makes someone a surgical candidate.

“There was a lot of education,” Sargent said. For the first year and a half, they would each spend an afternoon, or morning, a week in the clinic with the surgeons, observing them as they conducted physical assessments and interpreted imaging results.

Slowly the pair segued into doing partial assessments and, finally, they began conducting their own assessments.

It was “about developing an appreciation for what signs and symptoms indicate surgical intervention,” Malenchak said.

She learned to ask patients about bowel and bladder problems, about balance issues and about other neurological “red flags.”

“There has to be a very strong correlation between subjective history, objective history and what we see on imaging to make a case for them for surgery,” Sargent said.

The process works because Johnson and his fellow spine surgeons trust the physiotherapists doing the assessments, said Hamilton Hall, executive director of the Canadian Spine Society.

Spine surgeons can see a patient on an urgent basis as referred by the physiotherapists, knowing more definitively that it’s actually an urgent case.

“As long as they buy in, the system runs,” Hall said.

The Canadian Spine Society called for this type of triage system back in 2011, amid burgeoning wait-lists. The outlook is more positive now, Hall said, with variations of the Manitoba clinic existing and expanding across the country.

The result is more efficient, cost-effective care.

The spine assessment clinic received permanent funding in 2016, but even that is minimal: just enough to cover the cost of a full-time clerk and a full-time therapist (Malenchak and Sargent both work part-time), about $200,000.

Instead of patients waiting upwards of two years to see a surgeon who is likely to bounce them back to their family doctor, Malenchak and Sargent are able to refer a patient to outpatient physiotherapy services, or to the anesthesia pain clinic.

In some cases, they can even discharge a patient without needing to refer them elsewhere.

“It’s called the spine assessment clinic, but it’s almost poorly named,” Johnson said.

“It’s an assessment and treatment clinic because… if surgery is not appropriate, then what’s the plan? That’s been a huge part of our success.”

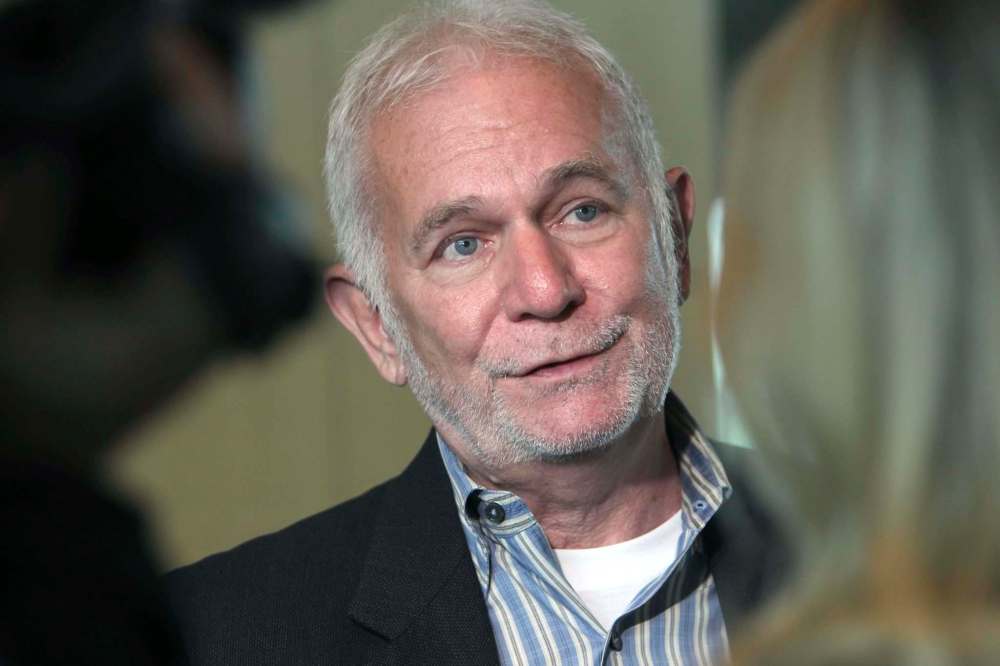

Its success is something Dr. David Peachey, the independent consultant who authored the report guiding many of the current health-system changes, wants to see replicated elsewhere.

He recommends psychologists play a similar screening role for psychiatrists as physiotherapists do for spine surgeons.

“With this model, the people that need a spinal assessment on an urgent basis get seen virtually the next day or the same day, so you’ve achieved timely access and quality in using the proper roles,” Peachey told the Free Press last month.

“The problem is pretty similar with psychiatry and spinal surgery,” he said. “That is, are you getting the right people to do these specialized services in a timely fashion?”

The authors of the Wait Times Task Force, released last month, would also like to see the spine clinic model replicated when it comes to combating high wait times for hip and knee surgeries, as well as MRIs.

In both cases, the task force feels that adapting the spine assessment clinic model could help cut down on unnecessary surgery assessment wait times and inappropriate MRI use.

While he said the government won’t speak to any specific projects in the near future, Health Minister Kelvin Goertzen said there’s always interest in “innovative and creative models that involve team-based service delivery.”

Opportunities that build on the spine assessment clinic concept are expected to be part of the clinical work at Shared Health.

jane.gerster@freepress.mb.caTwitter: @Jane_Gerster