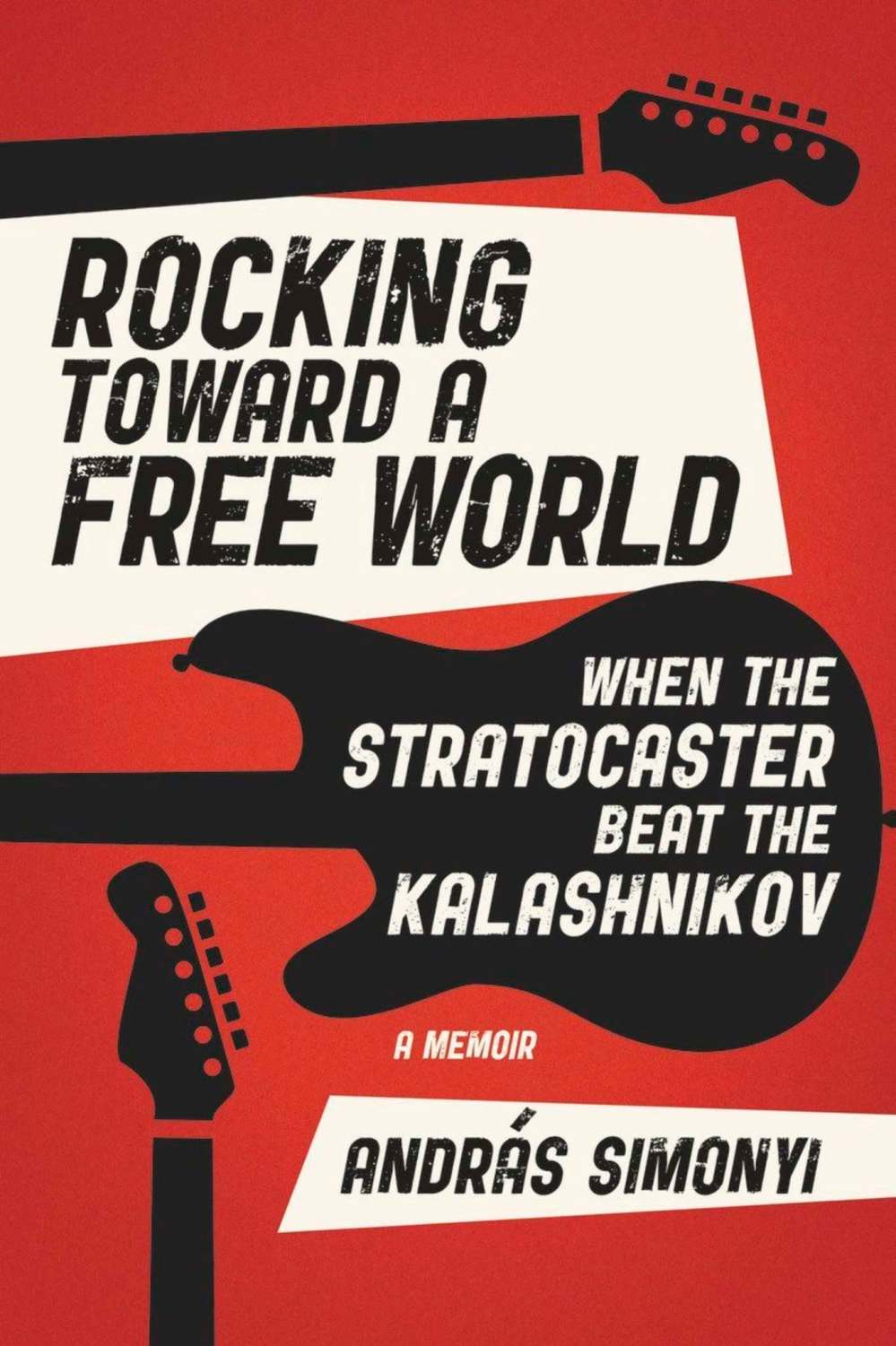

Hungarian diplomat’s rock roots revealed

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/07/2019 (2343 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Rock ’n’ roll, at base, is about freedom, gusto and rebellion — notions that conflict with the regimentation demanded of a totalitarian state.

Doctrinaire Marxist states know this. So they hate rock music.

Author András Simonyi is the former lead guitarist for 1960s Budapest rock band the Purple Generator. He’s also Hungary’s former ambassador to the United States.

His memoir is only about his first career — that of a teenage rock ’n’ roller who played guitar riffs against the background of an authoritarian system.

The first third of the book is a fairly humdrum coming-of-age memoir, made marginally exceptional only due to Simonyi growing up partly in dismally oppressive Hungary and partly in a democracy. His civil-servant father was posted to Copenhagen, so his family spent six years, which included Simonyi’s impressionable early teen years, in Denmark.

The early part of the memoir skips over just how dreary life in a Soviet puppet regime was — seemingly due to young Simonyi sometimes being oblivious to his privileged-kid status, unaware of the state’s increasingly pervasive control of most citizens’ lives.

But the pace accelerates, and so does the quality of the writing, as the memoirist warms to his own story — a warming triggered by two defining life events.

The first was a 1968 rock concert in Budapest by the British band Traffic.

Western rock bands were pretty much persona non grata behind the Iron Curtain in those days, but somehow Steve Winwood and company landed a groundbreaking gig in Budapest.

Sixteen-year-old Simonyi attended the concert, finessed an invite to the band’s post-concert hotel-room party, and chatted at length about music with Winwood. The next day, he escorted drummer Jim Capaldi and flutist/saxophonist Chris Wood on a daylong excursion to a nearby lakeside restaurant. His acquaintance with Winwood wasn’t fleeting; five decades later, the rock star and the retired diplomat remain friends.

The other defining event was the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia later that same year.

The “Prague Spring” communist government of Alexander Dubcek had initiated a series of liberalizing reforms. Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev saw this as “counter-revolutionary” and ordered Warsaw Pact troops and tanks to occupy Czechoslovakia and arrest Dubcek.

The Soviets’ brutal crushing of the Czech initiative to lessen state control and increase individual freedom chilled the reform movement in neighbouring Hungary.

The book ends abruptly and darkly in 1974 with the return to prominence of the “Butcher of Budapest,” Béla Biszku, so called for his brutal suppression of pockets of resistance after the failed 1956 Hungarian revolution. The “lackey of the Russians, a lapdog of Leonid Brezhnev” impaired the modest loosening of state control over citizens’ daily lives Hungarians had enjoyed.

As Simonyi sums it up, it took another “fifteen years before the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and Hungary and the other captive nations of Central and Eastern Europe walked free.” And though rock didn’t actually conquer communism, as Simonyi’s subtitle suggests, he nicely captures how it helped speed its exit.

And the retired diplomat still plays guitar. He now lives in Washington, D.C., where he fronts a band called the Coalition of the Willing.

Douglas J. Johnston is a Winnipeg lawyer and writer.