Punk’s poet laureate

Biography of the legendary Art Bergmann tackles the rocker’s rollicking highs and lows

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/11/2022 (1135 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In March 1990, I was a young reporter covering the Juno Awards in Toronto for the Winnipeg Sun. The awards show was broadcast on Sunday, March 18, but the weekend’s real action took place the night before, at a WEA Canada showcase in the Royal York Hotel.

As Crash Vegas performed, 37-year-old Vancouver punk Art Bergmann, in town to promote his upcoming album, Sexual Roulette, tried to crash the show by jumping up to join the band. After being ushered offstage Art, a long-established soil disturber, attempted to heave a heavy planter in the band’s direction but succeeded only in scattering its contents over the ballroom’s parquet dance floor.

I’d been introduced to Art just moments before by Shelley Breslaw, the transplanted Winnipegger who was the publicist for his label, Duke Street Records. He and I were scheduled to meet for an interview the next afternoon at his hotel near Maple Leaf Gardens.

Mikael Kjellstrom / Calgary Herald

Art Bergmann, seen here in 2007 near his home in Airdrie, Alta., has released three albums of new material in the last decade, including 2021’s Late Stage Empire Dementia.

Later that evening, Art stormed into a men’s washroom at the Royal York, yelling: “Do any of you f***ers have any drugs?”

Hearing no response, he shouted: “Of course you don’t — no one in Toronto does drugs anymore!”

Art managed to show up the next day, looking rather grey and still wearing the same clothes as the previous night. He waved away his antics as just “a bit of fun,” then drank coffee and smoked as we chatted.

Afterward, we stepped out of the hotel into a crowd of well-dressed, middle-aged adults standing outside the Gardens — parents waiting for children to emerge from a New Kids on the Block matinee. Art grinned broadly when I told him.

“Flipper ate your mothers,” he shouted, referring to the 1980s San Francisco punk band. “Flipper ate your mothers!”

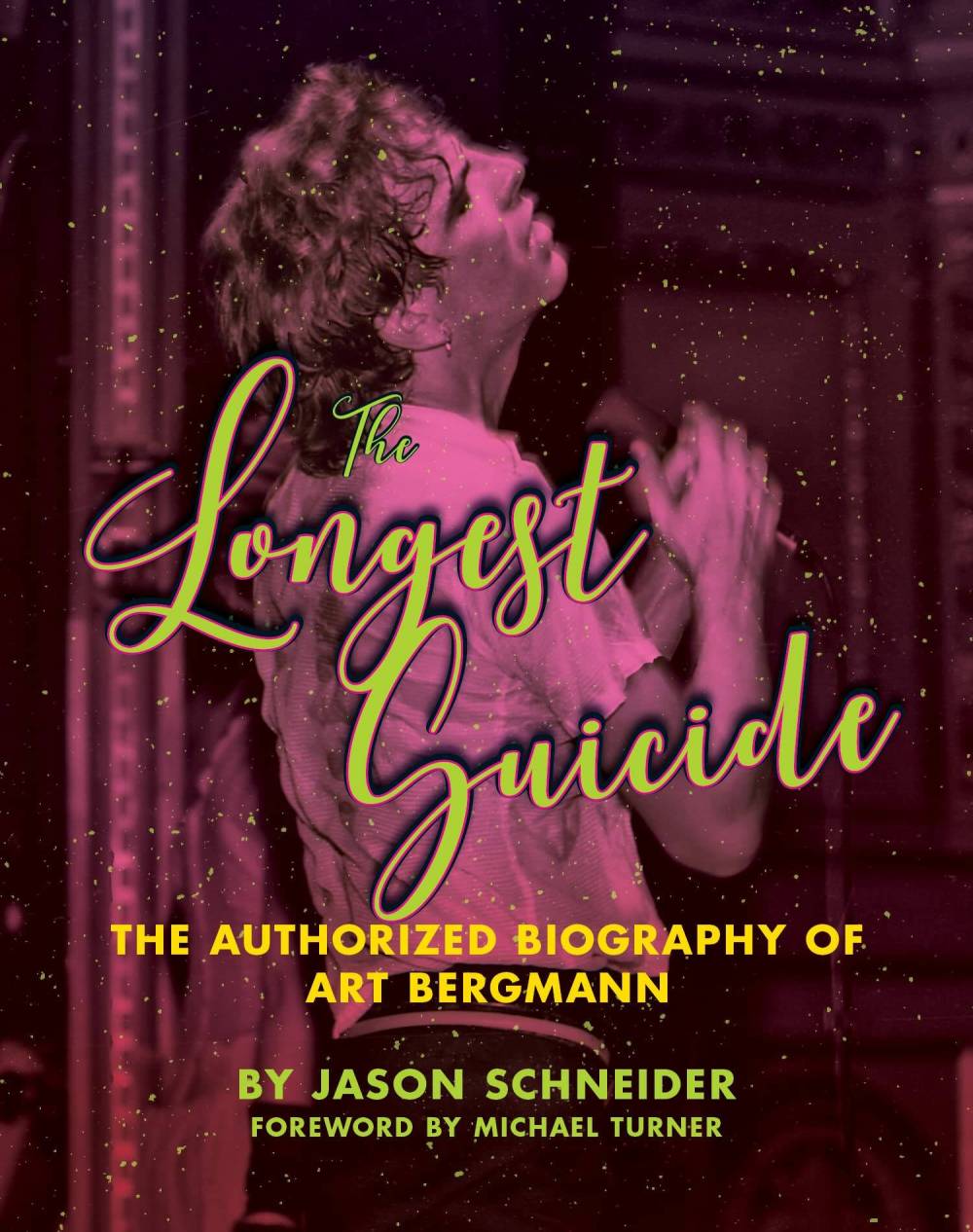

The Longest Suicide

He raised his fist in the air, repeated his cry… and disappeared into the crowd.

● ● ●

Jason Schneider, a veteran Canadian music journalist, takes on the unenviable task of separating the essence of Art Bergmann from the tangle of endless tales such as this one in The Longest Suicide: The Authorized Biography of Art Bergmann. Schneider is no stranger to the subject, having first tackled the story of Bergmann’s role in Vancouver’s nascent punk scene as co-author, with Michael Barclay and Ian A.D. Jack, of Have Not Been the Same: The CanRock Renaissance 1985-1995.

This biography, written with Art’s co-operation, eschews most of the ribald stories and chooses to tell the musical story of a brilliant but almost fatally flawed artist whose late-1970s recordings with Young Canadians are considered foundational, and whose solo work in the ’80s and ’90s revealed a master of rousing, darkly literate rock ’n’ roll unlike anything else coming out of this country (despite issues with producers and promotion).

Partly owing to his self-destructive behaviour, partly owing to poor management and partly owing to the music industry’s failure to “get” him, Bergmann never achieved the kind of success and financial stability he should have, although he did win the best alternative album Juno Award in 1996 for What Fresh Hell is This? (on the same day he was dropped by Sony Music Canada).

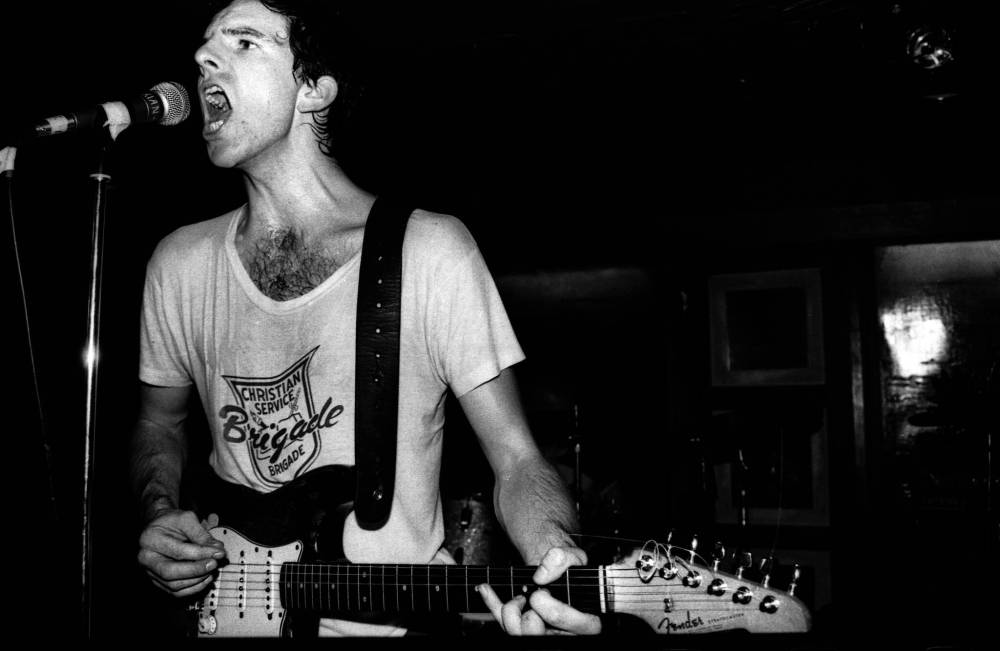

BEV DAVIES PHOTO

Art Bergmann during the Young Canadians’ last show.

By the late 1990s, Art and his wife, Sherri Decembrini (who, sadly, died unexpectedly this past March), were living an almost hand-to-mouth existence in Toronto before they moved, for family reasons, in 2005 to a farm just north of Calgary. They settled into a bucolic life and he eventually found his muse again. In the past decade, he’s released three independent albums of new material, including last year’s excellent Late Stage Empire Dementia. In 2020, Bergmann was installed as a member of the Order of Canada for his “indelible contributions to the Canadian punk music scene, and for his thought-provoking discourse on social, gender and racial inequalities.”

This is a tale well told in The Longest Suicide. The story of Art’s earliest years, his discovery of rock ’n’ roll and his first attempts at playing music is de rigueur in this kind of book, but Schneider’s best work is done as he paints, with the help of Bergmann and several bandmates and contemporaries, a vivid picture of Surrey, B.C., and the semi-rural expanse southwest of Vancouver as the Wild West of underground culture in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

It’s clear that the feral rock ’n’ roll spirit of the Shmorgs, Bergmann’s first real band, is something that has never left him.

John Kendle is a writer and editor who’s been writing about music in Winnipeg since 1985.