The ghosts of New Iceland Now a picturesque waterway popular for outdoor recreation, more than a century ago the Icelandic River was a hub of industry for waves of Nordic settlers in the Interlake

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/08/2023 (855 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In early August, musicians, vendors, runners, carnies, folks in horned helmets and the like converge on Gimli for Íslendingadagurinn, the Icelandic Festival of Manitoba.

And while it’s a weekend filled with fun events and some cultural touchstones, venturing beyond Gimli and all the fest’s fanfare offers another side of the Icelandic-Canadian experience in Manitoba — tangible examples of settler life along the western shore of Lake Winnipeg over the last 150-plus years.

Meandering its way through what was once New Iceland is the Icelandic River, which starts in the Rural Municipality of Fisher.

Before eventually emptying into Lake Winnipeg to the east, the river connects a pair of communities in the Bifrost-Riverton municipality with a shared history — Arborg and Riverton.

Today the river is a modest, picturesque waterway, home to walking trails, monuments and the odd kayaker. But in the late 19th century, the river and its banks was the hub of industry — fishing, lumber production, agriculture and more.

While both communities have evolved and flourished, stories from the older generations have vanished.

Eager to retain the traces of the past, residents in both Arborg and Riverton are working to preserve the history of New Iceland, and to restore remaining structures to their former, if not modest, glory so their legacy doesn’t completely disappear.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

The first group of Icelandic immigrants arrived on Willow Point near Gimli in October 1875, having left their failed settlement in Ontario.

Among them was Sigtryggur Jonasson, one of the first Icelanders to arrive in Canada in 1872, and who would become known as the father of New Iceland.

The immigrants, along with another larger group of Icelanders who arrived in 1876, settled on the western shores of Lake Winnipeg, with the 58-kilometre strip of land running from Boundary Creek near Winnipeg Beach north to Hecla eventually being dubbed New Iceland.

It wasn’t long before hardship befell the newcomers. That winter the smallpox virus decimated both the Icelandic settler and Indigenous communities. “Some families lost up to four or five children,” explains Nelson Gerrard, local historian, genealogist and a member of the Icelandic River Heritage Sites group.

Naming the homesteads

Visitors to the Rural Municipality of Bifrost-Riverton can discover where various Icelandic homesteads stood, and what they were named, thanks to an initiative through the Icelandic National League group in the 1980s.

Blue-and-white signs erected throughout the area indicate where homesteads once stood — and the names they had been given.

Visitors to the Rural Municipality of Bifrost-Riverton can discover where various Icelandic homesteads stood, and what they were named, thanks to an initiative through the Icelandic National League group in the 1980s.

Blue-and-white signs erected throughout the area indicate where homesteads once stood — and the names they had been given.

“Virtually every farmstead, homestead had a name at one time,” says Gerrard.

“When I first moved up here in 1979, I was aware of a lot of this history, but it wasn’t visible — you had to know that this was such-and-such a homestead yourself; there was nothing to show that.

“The names were quickly falling from memory as the older people passed away, and the names weren’t being used. Many people didn’t even know the homesteads had names.”

One of many signs that dot the region, signifying where original Icelandic settlers had their homesteads. (Mike Deal / Winnipeg Free Press)

One of many signs that dot the region, signifying where original Icelandic settlers had their homesteads. (Mike Deal / Winnipeg Free Press)

Subsequent years brought additional challenges. Exceptionally wet weather, accompanied by a brutal season of mosquitoes, arrived the following year.

Then came a religious clash within the Icelandic community in 1877-78, with one group led by Lutheran reverend Jón Bjarnason and the other by reverend Pall Thorlaksson. The groups had differing ideas about New Iceland’s future; Thorlaksson was more conservative, Bjarnason more liberal.

“The rivalry between the two groups turned neighbour against neighbour, family member against family member, and a lot of the hostility was directed at the founders of the settlement,” Gerrard says. Thorlaksson and many of his followers soon departed for what is now North Dakota.

Extensive flooding in 1880 was the last straw for some of the settlers, who pulled up roots and headed south to the Baldur-Glenboro area, leaving New Iceland’s population waning.

“There were very few left in Gimli… Arnes was almost totally abandoned, Hecla Island was all but abandoned and the Hnausa area was hard hit as well,” Gerrard says.

Those who stayed resided in and around what is now known as Riverton, where there were still jobs available thanks to Jonasson.

“He and partners had established a sawmill with logging operations, and they had bought a steamship called the Victoria and were providing employment. There was also a store that they ran — they extended credit, of course… they were also hauling lumber, which had been produced locally, by barge to Selkirk, where it was sold.”

After New Iceland became part of Manitoba in 1881, Jonasson would go on to serve as an MLA from 1896-99 and 1907-10. It was his dealings in government that helped revive the New Iceland region.

Jonasson was key in getting rail lines extended to Gimli in 1906, Arborg in 1910 and Riverton in 1914.

“Shortly after that, the influx of what we today call Ukrainian settlers began arriving,” Gerrard says.

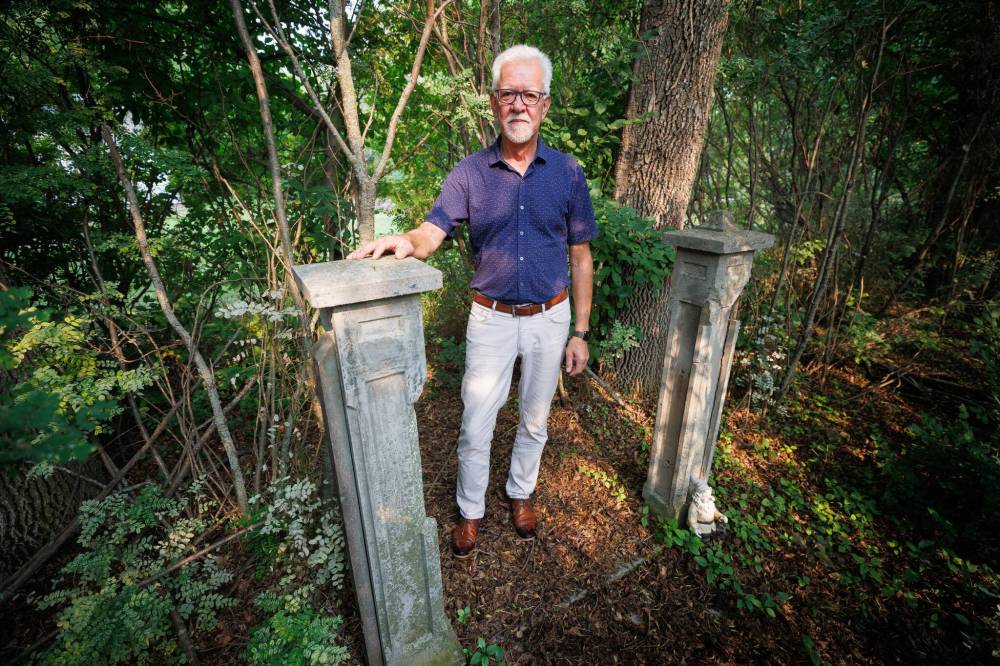

The Icelandic River is exceptionally low this summer. “The last few years have been so dry,” says Mayor Peter Dueck at his riverside home, which sits on the site of a former convent, orphanage and seniors’ centre.

“This year the river is so overgrown with weeds and lilypads — we don’t really have any current.”

Dueck, first elected mayor in 2018, is now in his second term in office. A “Fisher Branch boy,” as he says, Dueck moved to Arborg with his wife in 1995. His father-in-law started Vidir Solutions, which grew into a manufacturing company; he continues to work for Vidir, which is the Icelandic word for willow.

And while the river level might be low, Arborg — located about 70 minutes north of Winnipeg at the end of Highway 7 — is a community on the rise both population-wise, with 1,279 residents, and in general outlook.

“I would say pretty soon Winkler will want to be known as the Arborg of the south.”–Mayor Peter Dueck

Dueck cites many factors as part of the town’s upswing.

“First of all, this is obviously an agricultural-based community… farming is becoming quite a profitable enterprise for many people, especially the way land is appreciating. And our area grows some of the best canola seed in the province,” he says.

“But we are also blessed with an amazing manufacturing component in the area. We have in the neighbourhood of 400-500 manufacturing jobs in the vicinity.”

Those jobs have helped change the face of Arborg’s population.

“I think what would surprise a lot of people is how diverse the town is ethnically and culturally,” he says. “Because of the manufacturing jobs, the medical and technical jobs, we have a tremendous amount of cultural diversity. That’s really enriching our area.”

The rail line may no longer run to Arborg, but its history is still preserved — the former station, across the street from the popular Arborg Bakery, is now home to the town library, while the rail span that once traversed the Icelandic River is now a walking bridge.

Dueck’s property hints at traces of the past, which caused problems when he built his home on the site.

“Six hours into the project, we were behind schedule and over budget — we ran into the foundation of the old (convent/orphanage) building,” which they were unable to remove, he says.

Still standing on his property is an old outdoor brick oven, which Dueck reckons dates back to 1902, as well as the pillars that stood at the gate to the original property, tucked in the brush near his driveway.

For Dueck, the future of Arborg looks bright.

“When we want to feel good about ourselves, we call ourselves the Winkler of the north, because we have so many manufacturing jobs. But as mayor, I would say pretty soon Winkler will want to be known as the Arborg of the south,” he says, laughing.

Nowhere is Arborg’s slogan, “A Tradition With a Future,” better embodied than in the Arborg & District Multicultural Heritage Village and Campground.

Pat Eyolfson was among a group of businesswomen who helped create the heritage village in February 1999. “We weren’t tapping into tourism — we had the beautiful Icelandic River, but no drawing card for people to come to town other than if they were coming for groceries or clothing or whatever,” she explains.

Eyolfson and company struck a grassroots committee, became incorporated, got non-profit status and started the logistical work of moving the smattering of historic buildings still standing in New Iceland to what would become the heritage village.

The site is on the southeast end of town on Highway 68, tucked next to the river.

“We wanted good visibility when people would come into town,” Eyolfson says. “You see this beautiful village now nestled along the Icelandic River… you see it as you’re coming from the lake, from cottage country.”

The first structure, the Trausti Vigfússon building, was dragged to the site in October 2000.

“We moved it with two teams of horses, because that’s the way it was moved in 1898, from Riverton to the Geysir area… we wanted to recreate that,” she says.

“These two beautiful teams of horses drew this building down the highway; they were so proud, they held their heads up high — they were working.”

The last building to be moved was the Oddleifsson house, a homestead brought from Geysir dating back to the 1880s, and is likely the oldest surviving log house in New Iceland.

The Poplar Heights schoolhouse, also on site, was built in 1918 in the RM of Woodlands; it features one classroom with a second storey added in 1944.

“This is the school that my Afi (Icelandic term for grandfather) went to, and when I came here on a field trip I got to meet his teacher — he was volunteering here,” says young tour guide Emma Sigvaldason as she shows off the projectors, old photos, textbooks, inkwells and an original disciplinary strap in the classroom.

As indicated by the “multicultural” part of the village’s moniker, not every structure has Icelandic roots.

There’s the St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Parish Hall, St. Demetrius Ukrainian Catholic Church and the Kowalski House, formerly occupied by Pete and Betsy Kowalski, their three children and a teacher, who paid $15 in monthly rent for a room.

Then there’s the Hykaway grist mill, which was built near Meleb around 1910 by John Hykaway, a Ukranian-Canadian.

“When it would start up, they would engage the wind vanes and you could hear that sound for miles,” Eyolfson says. “Then the farmers would line up with their horses and wagons, bringing their grain to be milled into flour.”

Joe Stoyanowski has been instrumental in preserving the grounds. Opening the door to the grist mill, he points into the structure to highlight some of its unique characteristics. “There’s like a railroad track up there, with wheels on it — so the whole top turns,” he says.

The grist mill, Stoyanowski adds, was built by a blacksmith from Ukraine.

“I’m pretty sure he was self-taught,” he says. “He just had pictures of windmills from Holland; he developed his own pattern for everything. He didn’t have any real plans.”

Stoyanowski has a passion for the past. “I’ve been into antiques all my life. My dad grew up in the ’30s, during the Depression, and so everything to him was precious,” he says.

When it came time to furnish some of the buildings with items from the period in which they were built, Stoyanowski was able to pitch in.

“We were offered a 1890-something pump organ. But we’ve got organs in just about every house already.”–Joe Stoyanowski

“I collected cameras for years — I donated 275 cameras to the village,” adding “our biggest problem right now is we have to reject some donations because we have so many of them. Like sewing machines — we probably have 10 or 12 of them. We were offered a 1890-something pump organ. But we’ve got organs in just about every house already.”

In the back of the heritage village general store and auto garage (not an original building of the area, but built to look like one) is perhaps Stoyanowski’s most prized and most striking contribution to the heritage village — his father’s truck.

“He came out of the army, came out of the war,” Stoyanowski says. “He started his business, Veteran’s Garage in Arborg. And he needed a truck. And what he had was a ’28 Pontiac — it was kind of a rattletrap car.

“So he pulled the body off of it, and he found this ’32 Dodge coupe body, cut the coupe part off, which is the trunk on the back, and mounted it on here.

“And then he bought a Model T Ford box or Model A Ford box — I’m not sure which vintage it is — and he mounted that on there.”

The truck still sports wooden spokes on the tires; Stoyanowski restored the truck in 1985-86 and says it runs, although “right now we have a gas problem.”

Like Dueck, Eyolfson trumpets what “multicultural” looks like in today’s Arborg — far more than just European settlers.

Each fall, Arborg hosts a festival called Culturama. Food is front and centre along with entertainment provided by relative newcomers including from Bolivia, Ukraine, Britain, Nigeria, Philippines, Mexico, Belize.

“You pay $10 to come into the hall, you get a plate at the door and cutlery,” she says. “And you go around to every booth and see what they have on offer, on display…

“All these different cultures make your community strong. It becomes a close-knit community.”

The Icelandic River drains into Lake Winnipeg about four kilometres northeast of Riverton.

It flows within about 25 metres of where the Reggie Leach Arena stands on Main Street; Reggie Leach Drive, meanwhile, runs east-west and ends near the river walking bridge.

The former Stanley Cup and Conn Smythe trophy winner (and current Hockey Hall of Fame absentee) is modern-day Riverton’s most famous export; he was famously known as the Riverton Rifle while playing in the bigs during the 1970s, primarily with the Philadelphia Flyers.

Legendary goaltender Johnny Bower (left) presents the Conn Smythe trophy for NHL playoff MVP to Philadelphia Flyers winger Reggie Leach in Montreal in this June 9, 1976The street named after the Ojibwa sniper from Berens River First Nation ends at a statue of Riverton’s other well-known resident — Sigtryggur Jonasson, the father of New Iceland.

Located on Highway 8, anyone driving to Hecla ends up passing through the hamlet of around 500 people. It’s on Riverton’s main drag where Kahleigh’s Brew Barn and Kahleigh’s General Store are located, just a few doors from each other.

Kahleigh Olafson opened the eatery 10 years ago. “The restaurant is extremely busy throughout the year. It’s lots of work, but there’s constant traffic through Riverton, so that’s good,” she says.

Busy season used to be summer, when cottagers would be heading north to Hecla-Grindstone Provincial Park or holed up at nearby Balaton Beach or Hnausa (pronounced “nay-sa”).

“Since COVID, the ice-fishing around Sandy Bar Beach, which is just a few miles from Riverton, keeps us busy in the winter,” she says.

The general store, meanwhile, has been open for a year. It offers groceries, toys, ice cream in the summer and plenty of other goods.

Olafson lived in Riverton until she was 18, moved to Winnipeg for a few years and then came back.

“I always knew I wanted to have my kids grow up in Riverton; it’s always been home to me,” she says. “It’s a super close-knit community. My oldest is nine; I can let him go uptown by himself and he’s safe. Everybody keeps an eye on each other’s kids. It’s a good place to live and bring up kids.”

Like Arborg, Riverton is a community on the upswing.

“There’s a lot more tourism in Riverton compared to 10 years ago when I started the restaurant,” Olafson says. “Now if it’s packed at lunch and I come out from the kitchen, chances are I don’t know anybody in the restaurant, whereas before it was all locals.”

And like Arborg, Riverton is seeing plenty of newcomers take root in the community, notably from Ukraine, and the reception has been welcoming.

“Most of them really like it here,” Olafson says. “They’re happy they ended up here… when they have a baby, somebody in the community will throw them a baby shower. Whereas when they move to the big cities, they don’t have as much of that.

“The community really comes together here, tries to make them feel welcome in Riverton.”

Riverton has managed to keep an eye on the future while retaining elements of its past.

The community’s railway station, long shuttered, has been converted into the Riverton Transportation and Heritage Museum. The ghost of the tracks can be seen heading south between rows of trees near Main Street.

A statue of Sigtryggur Jonasson stands at the foot of the foot bridge spanning the Icelandic River, the fourth to stand in the spot since 1892 (the previous three were destroyed by ice floes).

And just across the river’s banks are a pair of houses with a long history in the area, and which are being restored to their former glory.

The Engimyri house on Queen Street sits on the spot where it was built; the oldest part of the house (which has seen a number of more recent additions) dates back to 1900, says Gerrard, who lives two properties away and has helped spearhead the restoration.

An entire portion of the house was moved to King Street in 1915 and transformed into its own structure — it still exists, but “has been modified beyond recognition,” he says. What remains on the original spot has been carefully restored.

“When we took over this house about 12-13 years ago, it was a wreck. It was really on the brink — the roof was leaking, windows were broken, vandals had been in and parts were starting to pull up, parts of the foundation were failing,” he says.

“Usually those houses are done. We caught it just in time. And it’s now good for another 100 years.”

Originally constructed by Trausti Vigfússon and Jónas Jónasson, Engimyri was the homestead of Tómas Jónasson and Gudrun Johannesdóttir, who arrived in New Iceland among the second wave of immigrants.

“This couple actually spent the first winter on Hecla, and then in 1877, the spring of ’77, moved in here onto this property. It’s still owned by the same family,” Gerrard explains.

“Tómas Jónasson was the first owner; his son, Tómas took over from them. And then his son, Tómas took over from him. And now there’s a fourth Tómas that still owns the property. We have a 99-year lease,” Gerrard says.

Engimyri has been meticulously restored, its contents a reflection of the time the Jónassons homesteaded here. And from 1922 to 1928, they had a rather important guest lodging in one of their rooms.

“This room is significant because it was Sigtryggur Jonasson’s office,” Gerrard says as he surveys a small room ordained with books, a trunk and other items owned by the father of New Iceland. “He spent eight years here in his semi-retirement.”

Sigtryggur Jonasson died in 1942 at age 90.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

“He kind of outlived his generation, and died in not obscurity, but in very quiet retirement,” Gerrard says.

“As far as his physical legacy, there’s no house. He owned several beautiful houses throughout his life, but this is the only physical space left that he occupied. And he was here as a renter from his nephew — he was a brother to Tómas.”

Next to Engimyri is another house in the process of being restored, although it’s much further from being completed. Fagriskogur, as it’s called, had been used as a summer home for a number of years before Gerrard and the Icelandic Heritage River Sites crew took it over.

Like Engimyri, Fagriskogur (which means “beautiful forest”) has required extensive restoration — that is, after paying $12,000 to move the building and another $15,000 to build the foundation.

“There was all kinds of structural work once it was lowered, because this is actually four different buildings,” Gerrard explains.

On the wall of Fagriskogur, one of the oldest log structures still standing in New Iceland, hangs portraits of a couple — Olafur Oddsson and Kristbjorg Antoniusardottir, the original proprietors of the homestead.

Dream visit protects gravesite

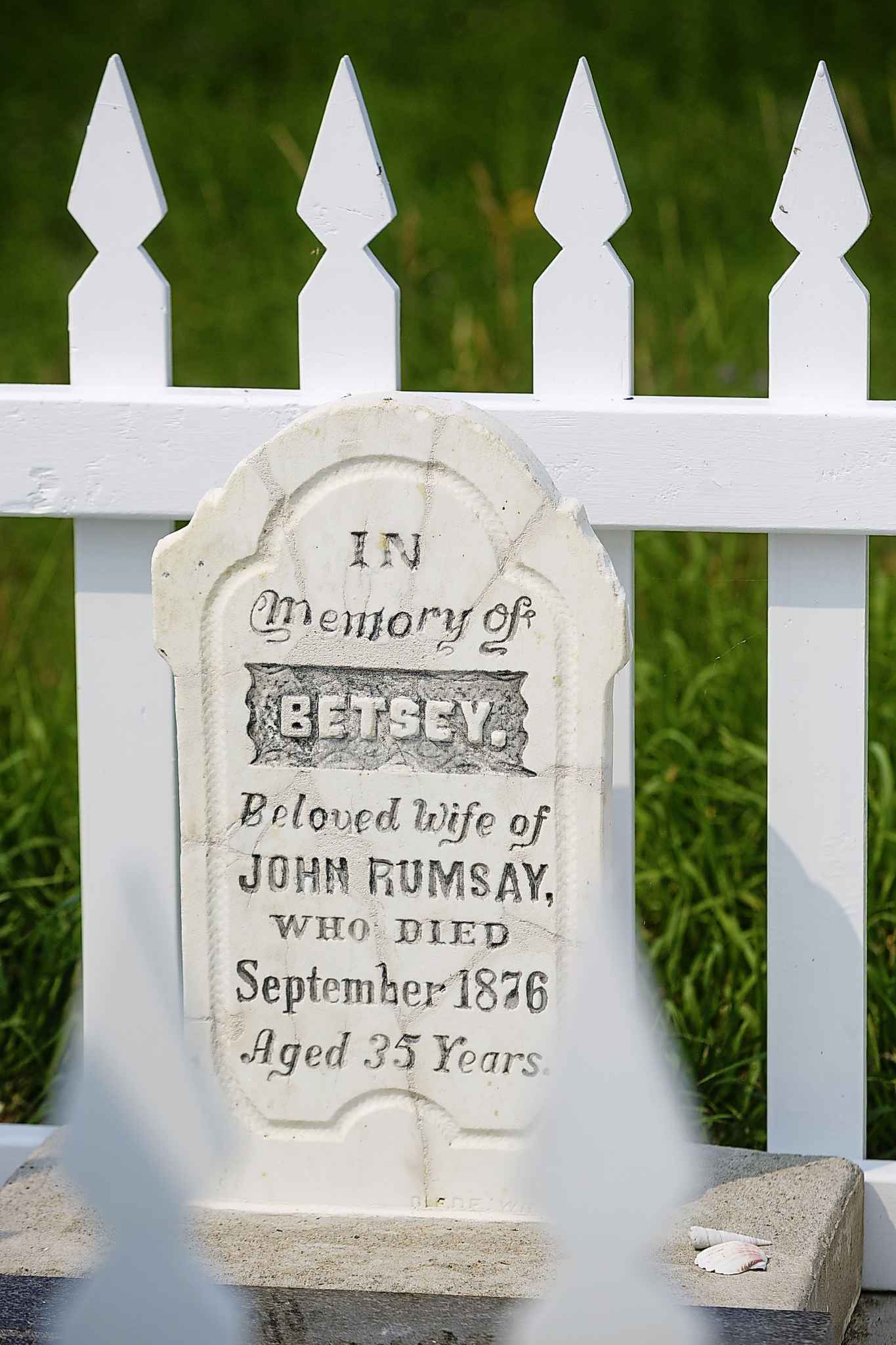

Among those who saw multiple family members die from smallpox in the 1876 outbreak was John Ramsay, a Saulteaux member of the Sandy Bar Band, who lost his wife Betsey and three of their four children to the disease.

Years later, John travelled south to Lower Fort Garry on a toboggan loaded up with many of his best furs, which he traded for a headstone for Betsey.

Among those who saw multiple family members die from smallpox in the 1876 outbreak was John Ramsay, a Saulteaux member of the Sandy Bar Band, who lost his wife Betsey and three of their four children to the disease.

Years later, John travelled south to Lower Fort Garry on a toboggan loaded up with many of his best furs, which he traded for a headstone for Betsey.

The Ramsays’ resting place is in a field near the shores of Lake Winnipeg, where the Sandy Bar settlement once was. It is inaccessible parts of the year, and tough to get to even when it is accessible.

Follow Provincial Road 222 west to the beach, then look north. In a field, among hay bales, there’s a shock of white — a brightly painted picket fence where Betsey, John and family are laid to rest.

The Betsey Ramsay gravesite, located a few minutes walk north of the Kaltenthaler Beach on Lake Winnipeg. (Mike Deal / Winnipeg Free Press)

The Betsey Ramsay gravesite, located a few minutes walk north of the Kaltenthaler Beach on Lake Winnipeg. (Mike Deal / Winnipeg Free Press)

The Ramsays’ story connects to Trausti Vigfússon, whose log house was the first building moved to the Arborg & District Multicultural Heritage Village in 2000.

Vigfússon was said to have been visited by John Ramsay (after his death) in a dream; he asked Vigfússon to rebuild the picket fence and tend to Betsey’s grave, which he did. (Various accounts mention the potential for good luck, or the threat of bad luck, based on what Vigfússon decided to do or not do.)

The RM of Bifrost-Riverton declared the grave a historic site in 1989.

Today, Vigfússon’s handiwork at the gravesite has been touched up with a rebuilt fence and a fresh coat of paint, and the splintering headstone (said to be the first stone grave marker in the area) was restored this past January.

The Betsey Ramsay gravesite located a few minutes walk north of the Kaltenthaler Beach on Lake Winnipeg. John Ramsay lost his wife Betsey and four of their five children to smallpox. (Mike Deal / Winnipeg Free Press)

The Betsey Ramsay gravesite located a few minutes walk north of the Kaltenthaler Beach on Lake Winnipeg. John Ramsay lost his wife Betsey and four of their five children to smallpox. (Mike Deal / Winnipeg Free Press)

“One of their descendants has been a major, major supporter in terms of making it possible for us to undertake the restoration, which will happen this fall.”

The plan is to turn the house into a centre that focuses on folklore — factual legends, tales of the huldúfolk (Icelandic elves), ghost stories and more.

“The house is said to be haunted. I’ve heard stories about this from more than one source,” Gerrard says.

“There’s a little old woman who appears at the top of the stairs, appears and disappears. And then there’s the half a man who climbs the stairs,” says Gerrard, adding with a laugh, “although I don’t know which half.”

Gerrard’s own property, dubbed Viðivellir and located next door to Fagriskogur, has a history of its own.

The property was owned by poet, composer, satirist and playwright Guttormer J. Guttormson, considered the greatest Icelandic poet born in North America (Stephan G. Stephansson, the better-known Icelandic writer of the time, was born in Iceland).

Gerrard has converted the property back into a farm, and also tends to the Nes cemetery on the adjacent property near the east side of the Icelandic River — a spot with few actual grave markers, but which is home to the bodies of many Icelandic and Indigenous victims of the 1876 smallpox outbreak.

Like the Icelandic River, the communities of Arborg and Riverton have waxed and waned through the years.

But like the lazy little river that snakes its way through both communities, they have managed to meander forward while retaining traces of the past.

ben.sigurdson@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Sigurdson

Literary editor, drinks writer

Ben Sigurdson is the Free Press‘s literary editor and drinks writer. He graduated with a master of arts degree in English from the University of Manitoba in 2005, the same year he began writing Uncorked, the weekly Free Press drinks column. He joined the Free Press full time in 2013 as a copy editor before being appointed literary editor in 2014. Read more about Ben.

In addition to providing opinions and analysis on wine and drinks, Ben oversees a team of freelance book reviewers and produces content for the arts and life section, all of which is reviewed by the Free Press’s editing team before being posted online or published in print. It’s part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.