Life, death and lore Eastern Manitoba village of Elma has had its ups and downs and enduring mysteries

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/06/2023 (893 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

ELMA — For some, this is the end of the road. For others, it’s just the beginning.

The small village of 100 or so people sits at the intersection of provincial highways 15 and 11, roughly 80 kilometres east of Winnipeg.

Elma’s main cluster of homes is surrounded by the rocky, meandering Whitemouth River to the north and the linear, man-made Canadian National Railway tracks to the south. Tidy yards and thick swaths of forest open onto expanses of farmland in every direction — livestock, grain, strawberries.

On the edge of Whiteshell cabin country, the place boasts natural beauty and strange landmarks made stranger by local lore.

The history of the town is deeply personal. Many who live in Elma are descendants of the original pioneers, others have been called here by opportunity and cosmic destiny.

As one resident put it: “The people who are here really want to be here.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Elma is home to about 100 residents, many of whom are descendants of the original pioneers.

Welcome to Elma, home of a beloved midwife

Before Lydia Pajunen was a midwife, she was a “classy lady.”

“They had nice clothes, a nice house,” daughter Aili Lean says of her parents’ life in urban Finland prior to settling in rural Manitoba. “Here, there was nothing but mud.”

SUPPLIED Pajunen, Aili, and Lydia holding Toini, 1926.

Lydia’s name is the first thing you’ll see on your way into Elma. Large blue welcome signs proclaiming her prominence were erected in 2004 ahead of the RM of Whitemouth’s centennial anniversary. While many small towns pay homage to regional celebrities and athletes, it’s rare to see a historic caregiver celebrated.

(The nearby town of Rennie, on the other hand, welcomes visitors as the “Home of Something… or Somebody Famous… Someday… Maybe.”)

Lydia and her husband Walter Pajunen arrived at the settlement — known as Janow until the construction of the railroad — in 1902. According to an uncredited article in The Carillon in 1970, the pair spent their first winter working at a bush camp, where he cut pulpwood and she cooked and snared rabbits. Walter later took a job with CN, pushing dirt to build the rail bed, while Lydia worked at a girls’ home in Winnipeg. Their first log cabin included a sauna.

The couple’s early days in Canada were filled with heartache. Their first daughter died during the ship crossing and was buried at sea. Several years later, their second-born, a son, died in infancy.

The Pajunens returned to Finland in 1906, where Walter purchased and ran a successful butcher shop. Despite the prosperous business, they moved back to Elma in 1910 and established a small farm on the outskirts of town, joining a raft of Polish, Finnish, and later, Ukrainian immigrants to permanently settle in the area.

Whether Lydia was self-taught or completed a midwifery course in Finland is up for debate. Either way, she began attending births upon her return to Eastman. Over the course of her 40-year career, she delivered an estimated 2,000 babies and became the de facto doctor and social worker for the region.

Daughter Aili Lean was born in 1922, followed by sister Toini Hawthorn three years later. The sisters — now 100- and 97-years-old, respectively — met with the Free Press recently to share memories of their mother and of life in Elma.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Toini Hawthorn (left) and Aili Lean are the elderly daughters of a Finnish-born midwife who delivered an estimated 2,000 babies in the Elma area during her career.

Being the area’s first midwife was a busy job.

“We missed her,” Hawthorn says. “These births would take time, so sometimes she’d be away two nights and our dad and the two of us would be home alone.”

Whenever a woman went into labour, family members arrived on the Pajunens’ doorstep to solicit Lydia’s services. Roads were sparse at the time, so her modes of transportation varied across the vast territory.

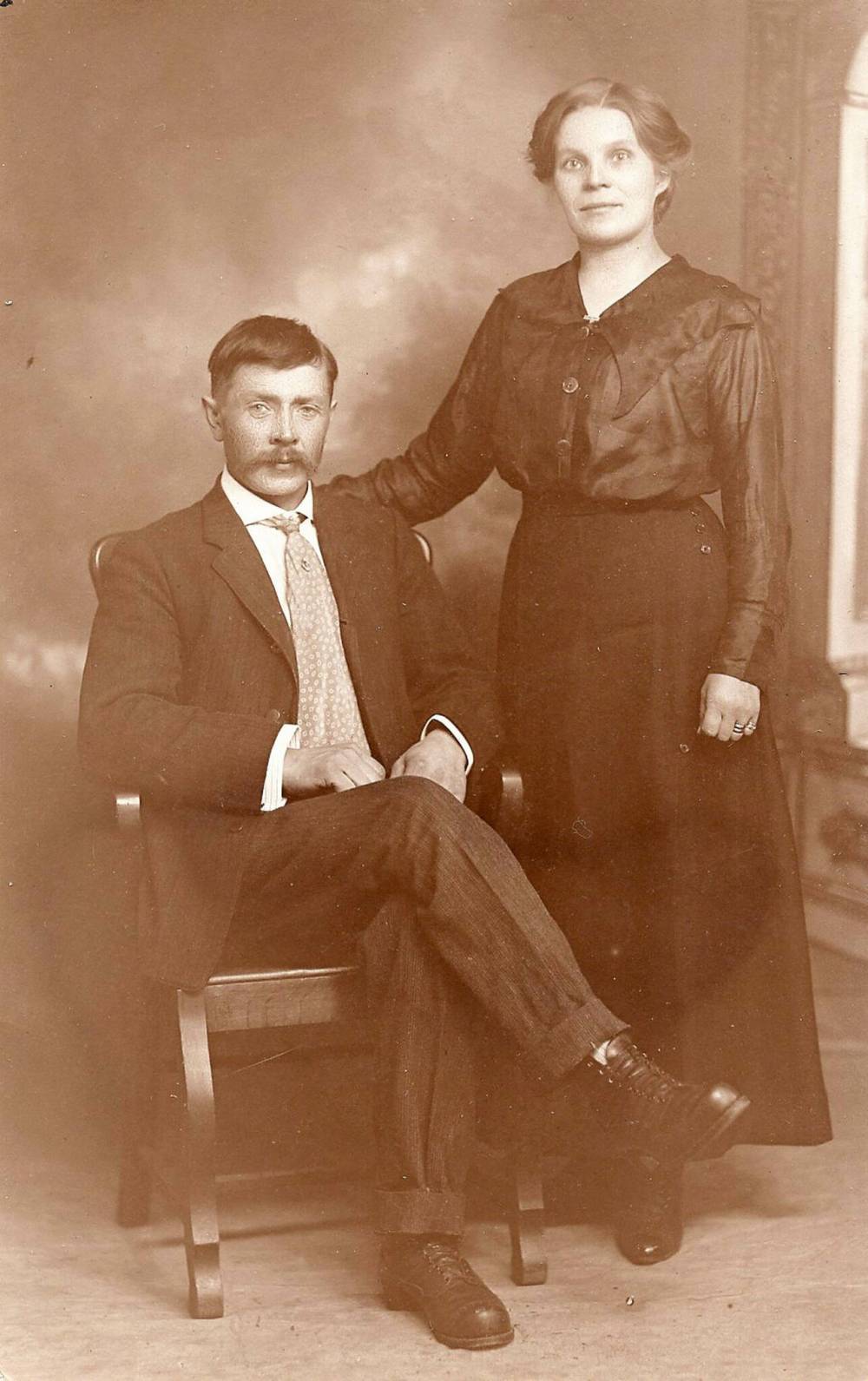

SUPPLIED Pajunen, Walter and Lydia

“She walked, she skied, she went by boat, she went by handcar on the railroad, there were cars and horses and dog sleds,” Lean says. “All kinds of ways.”

If the family lived close by, Lydia visited regularly in the days after the birth for checkups and to help bathe the newborns. She provided mothers with sugar to be boiled in water and given as an infant nutritional supplement, according to accounts in Trails to Rails to Highways, a book of local history.

Payment often came in the form of foodstuffs. What little money she did earn from midwifery was used to purchase medical supplies, which Lydia used to treat patients young and old.

“People came to her with all their problems — if they got hurt, if they were sick,” Lean says.

She provided care for minor injuries and offered a meal or a compassionate ear to those in need. When the issue was beyond her scope, Lydia directed house callers to the hospital in Winnipeg, often taking up a collection among neighbours to pay for those unable to afford train tickets into the city.

Finances were equally tight on the Pajunen homestead.

“It wasn’t a bowl of cherries,” Hawthorn says, recalling that she once received a spoon and a towel as Christmas gifts. “But we didn’t know any different… there were other kids in the very same boat as we were, so we didn’t stand out.”

Lydia is described as a “jack-of-all-trades” by her daughters. She was a dedicated wife, mother and master baker, who specialized in bread and buns. She spun wool and sold mittens, socks and quilts to supplement the family’s meagre farming income. Walter occasionally butchered livestock and sold the cuts in town out of the back of a wooden wagon.

The family lived south of Elma proper in a log cabin with a big living room, two bedrooms and no electricity. They kept a garden, cows and chickens.

Lean and Hawthorn spoke Finnish as their first language and learned English in school, which they attended from grades one to eight. Childhood involved a lot of walking.

“We walked three miles to school everyday,” Lean says. “And then we walked to meet the train in the evening.”

The Elma train station served as a gathering place for local youth, who eagerly volunteered to pick up the mail as a cover for socializing. (VIA Rail still provides weekly service through Elma, but the town’s charming former station was demolished in the 1960s.)

“You didn’t get mail every day, but we went to town anyway,” Hawthorn says with a laugh. “That was our entertainment.”

The sister’s paths diverged in adulthood. Hawthorn moved to Winnipeg, where she married and raised three children; Lean stayed in Elma, raising four boys a stone’s throw from her childhood home. She married another local and enjoyed a career growing trees in a nearby provincial greenhouse.

Lean, who now lives in Winnipeg, visited Elma recently to see a wooden bust of her mother created by local carver Walter Keller — the piece is currently on display at the Whitemouth Municipal Museum. The town isn’t what it used to be, she says.

She recalls a small but lively community-oriented village, where residents got together for baseball games, wiener roasts and dances. For decades, Elma was a rail hub with a bustling hotel, two active churches, multiple grocery stores and several local industries — including a mill, grain elevator and the aforementioned train station. Modern highways spelled the end of the boom years as services relocated to larger centres.

Still, Elma remains home. And it will always be “Home of Midwife Lydia Pajunen.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS A carved bust of Lydia Pajunen is on display at the Whitemouth Municipal Museum.

Lydia’s legacy lives on through local signage and local memories.

“She brought me into this world,” exclaims Patsy Kozak when reached by phone.

The longtime Elma correspondent for The Carillon was born in 1943 and formed a close relationship with the midwife growing up. She remembers a woman who was kind and caring, petite and powerful. She was beloved by kids and adults alike.

Lydia worked as a midwife until the 1950s, when a hospital opened in the adjacent town of Whitemouth. She died in 1965 at the age of 81.

Neither of her daughters are surprised by the recognition she’s received.

“I’m proud of her, she was a good lady,” says Lean, who, after her mother’s death, helped establish the former Lydia Pajunen Hospital Guild, which raised funds for health services in the municipality.

“It’s well-deserved,” Hawthorn says of the posthumous honours. “I realized when I was quite small that she was a little different than the other ladies — she did more, she was a very friendly, kind person.”

A sleepy village with a nightmarish past

Inside the chain-link fence bordering the Stony Hill Cemetery exists an arresting monument to a horrific local tragedy. A single grave, larger than the rest, marked by seven tombstones etched with identical death dates.

In the early morning hours of Jan. 29, 1932, seven members of an Elma farming family were murdered in their beds. The killing of Martin Sitar, his wife Josephine and five of his children remains one of the deadliest mass murders in modern Manitoba history.

Thomas Hreczkosy — whose last name is spelled a myriad of ways in newspaper accounts of the tragedy — was sentenced to death, and later committed to a psychiatric hospital, for the crime.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS The graves of the Sitar family, victims of a brutal axe murderer in the 1930s, at Stony Hill Cemetery .

The 28-year-old Polish labourer was Martin’s nephew who found work on the family farm after immigrating to Canada. In a confession after his arrest, Hreczkosy reportedly told police he had been visited by the devil and commanded by a “large buzzing black fly” to kill his relatives.

After finishing his morning chores, Hreczkosy entered the Sitars’ small farmhouse and bludgeoned Martin with an axe. He attacked Josephine in the same brutal manner before moving on to his cousins — Frank, 20, Walter, 11, Bert, 10, Jennie, 7, and Paul, 4 — and lighting the house on fire.

Neighbours noticed the blaze and rushed to help, pulling out several of the victims before the structure collapsed. The youngest, Paul, survived the attack and was rushed to St. Boniface Hospital in blizzard conditions on a special train. He later succumbed to his injuries, but not before allegedly declaring “Tom did it to us,” during a brief moment of consciousness.

The murders made international news with an Associated Press dispatch from Elma appearing in the New York Times — although many names and details were incorrect, including the number of victims.

The missing killer prompted a massive manhunt. Hreczkosy eluded police for five days until he was discovered, cold and hungry, along the railroad near Contour, a speck on the map 15 kilometres west of Elma.

Martin Sitar followed his older brothers from Poland to eastern Manitoba in 1900. He was an aggressive farmer, according to a local history website, who owned the area’s first steam engine and threshing machine. Josephine was Martin’s third wife; he was survived by five adult children, some of whom carried on the farming business.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS The Stony Hill Cemetery near Elma.

The Sitars are buried in Stony Hill Cemetery, a small, well-kept graveyard down a quiet country road and a few hundred metres from the site of the family’s former farmhouse.

Mass murder isn’t the only grim chapter in Elma’s history.

A decade earlier, the village was ravaged by a massive fire that wiped out the entire business section and left dozens of residents, including 27 children, destitute and homeless.

An account of the fire published in the Manitoba Free Press described the disaster as a total loss with damages nearing $60,000. The proprietor of the local general store was awoken by an explosion at a vacant house adjoining his property.

Within minutes, 10 buildings along the town’s main strip — including the post office, a boarding house, three warehouses and two stables — were engulfed in flames. The speed at which the flames spread gave the Deputy Fire Commissioner reason to believe coal oil or gasoline had been poured on two of the structures.

There were no local firefighting services at the time.

Four years later, in 1926, six people died and two were injured when a pair of freight trains collided head-on at the bridge over the Whitemouth River near Elma. One engine was carrying livestock, the other grain.

The crash was the worst CN accident to date and left injured cows, pigs and train cars scattered throughout the area. Several Elma residents were arrested for allegedly pilfering the wreck.

A new wave of pioneers

Al Capone was mentioned at least three different times during the Free Press’s recent trip to Elma.

While the infamous Chicago gangster likely has no tangible connection to the hamlet in eastern Manitoba, the town harbours odd relics rife with mystery.

For Noel Martin and Randa Jag, prohibition-era bootlegging is only one possible explanation for the more than 60 metres of concrete tunnels running underneath their property.

“There was a rumour linking it to Al Capone,” Jag says. “And then you see the building and it spikes your interest.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Noel Martin shows a capped entrance to underground tunnels on his property in Elma.

The couple purchased the historic pool hall and castle-like residence on Railway Avenue (Elma’s main drag) seven years ago and have been slowly unearthing its secrets ever since.

Martin has crawled through a dozen metres of the dank, claustrophobic passageways, which appear to branch out from beneath the home’s basement coal chute towards the Whitemouth River and the CN line across the road. Peering into the curious cranny, suddenly a hooch smuggling circuit from the United States seems entirely within the realm of possibilities. It’s also rumoured that the tunnels were used by draft dodgers during the Second World War.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Martin has explored the network of tunnels that begins underneath his property.

The original pool hall was destroyed by fire in 1922 and later rebuilt by Peter Kolega, although it’s unclear if the former owner had anything to do with the tunnels. Adding to the oddity is Kolega’s choice of building materials — the thick walls of the pool room, basement confectionery and detached home are made of flattened tin cans smeared with concrete.

Martin and Jag are the most recent caretakers of the designated historic site. Learning about its past has become something of an obsession.

“It’s like finding your pyramid in the sand,” says Martin, who has spent countless hours sifting through online archives and chatting with informed residents. “There’s more to what’s being told and there are still things that are unanswered. Until I find out everything about it, then maybe I’ll relax.”

Jag is ready to relax. Living in a museum can distract from building a future.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Noel Martin and Randa Jag purchased the old pool hall and castle-like residence seven years ago.

Both originally from Winnipeg, the couple found each other at the fateful crossroads of Elma. Martin purchased a property in the heart of the Agassiz Forest in 2006, after driving down the Old 15 highway on a whim. Jag, a self-described gypsy, followed a vision in a dream and “crash-landed” in town several years later.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Martin shows balls they found in the old pool hall.

“It was just so destined and lined in the cards that we were meant to be here,” she says, speaking literally about the result of tarot readings.

In addition to fixing up the pool hall, the pair are raising four daughters and operating a homestead on Martin’s rural property. Prior to the pandemic, they ran a farmer’s market that capitalized on the influx of weekend lakebound traffic. They enjoy the peace and quiet of the area — which they characterize as insular, but welcoming — and see ample opportunity to thrive in Elma.

“I love it here,” says Jag, who regularly updates the hall’s street-facing window display with artwork and positive messaging. “Maybe we can get the market going again and that can be a port of trade and people can spend more time building community.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Realtor Stacey Harron at the old hotel, now for sale.

Realtor Stacey Harron describes Elma’s population as stable.

“Which is important,” she says. “Some small towns in Manitoba lose their main industry and then they’re hooped and their populations decline.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS The hotel, now up for sale, comes with mismatched furniture and other odds and ends.

Many who live in the village commute elsewhere for work. While freight trains still barrel through town every few hours, the local rail industry has waned significantly — making businesses like the Elma Hotel obsolete.

Still, when the six-room, two-storey hotel and restaurant closed down in 2007 it was the village’s main gathering place and a “booming establishment,” says Harron.

Re-constructed in the 1920s, the beverage room was open to men only, forcing women to imbibe separately up the street at the pool hall. Today, the vacant building is a mix of wood panelling, retro green carpeting and mismatched furniture. A smudged chalkboard menu advertises fries for $5 and poutine for $8.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS The old hotel, which closed in 2007, was once a booming establishment.

Harron is hopeful about finding a new owner who can bring the place back to its former glory.

“These little small-town bars and restaurants, they do really well,” she says. “Because there really isn’t anything else in the area.”

After the town signs, the second thing you’ll see on your way into Elma is a handsome little shed boasting iced coffee, sandwiches and chicken strips. Andrew Goossen opened the Trail’s End Coffee shop last year as an expansion of his coffee roasting business.

Originally from Missouri, Goossen moved to the area in 2012 after marrying a local. They currently live on a farm south of town, where he operates a small roastery and packages coffee blends for distribution across Eastman — including a Whiteshell Blend designed to pair well with the area’s drinking water.

The midwestern transplant now considers Elma his hometown and the empty plot along Highway 15 seemed like the perfect spot to court new customers. A cabinet maker by trade, he retrofitted the prefabricated shed to house a small kitchen, café counter and retail space. Wednesday through Saturday, visitors can dig into snacks and specialty beverages at a pair of picnic tables outside.

So far, business has been sporadic.

“Sales have been up and down,” Goossen says in a thoughtful drawl. “(The locals) like having it here… but the population out here alone cannot support a business because that would take them comin’ here every day and I don’t expect them to do that.”

Like everything in Elma, the location for Goossen’s venture seems to have been preordained. His business name, Trail’s End Coffee, is a nod to the farm he grew up on in Missouri. Of course his new home would be at the terminus of a very different trail.

“It fit really well with up here,” he says. “We’re at the end of the 15, right at the shield’s edge and on the edge of the boreal forest.”

Goossen isn’t the only new business owner in town. Last month, Jen Lee and her husband took over operations at the Elma Country Store. Her parents ran the busy grocery, liquor and hardware shop for more than a decade and she spent many summers helping out behind the till.

“We know everybody, pretty much,” she says. “They’ve all welcomed (us).”

Lee’s parents convinced the previous owners to sell after falling in love with the shop during a road trip. The second-generation owners jumped on the opportunity to run the corner store after being forced to close their sushi restaurant in downtown Winnipeg amid the pandemic.

“Destiny? I don’t know,” Lee posits, unprompted.

Elma is easy to miss, but those who live here recognize its significance. As a place with a strange law of attraction. As a place full of serendipity, for better or worse.

Thanks to the “Elma Grapevine,” which proved invaluable in helping this reporter make many local connections. And thanks to Thelma Findlay and resident historian Jim Castle who freely shared much of their own research.

eva.wasney@winnipegfreepress.com

Twitter: @evawasney

Free Press Field Trips

Snowflake preserves and celebrates its history, from homestead and rail hub to nostalgic vestige of the Prairies’ past

Posted:

SNOWFLAKE, Man. — This southern Manitoba community’s two grain elevators tower on the horizon while driving south along bumpy Highway 242.

Eva Wasney has been a reporter with the Free Press Arts & Life department since 2019. Read more about Eva.

Every piece of reporting Eva produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.