Little latitude for objective evaluation Inquests into fatal shootings involving police routinely avoid examining systemic issues; instead rely heavily on a narrative driven by law enforcement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/09/2023 (814 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Under Canadian law, officers must believe their own life, or that of another, is fundamentally at risk — or at risk of “grievous bodily harm” — to use lethal force.

The Inquest Files

A Free Press investigation into judicial oversight of fatal shootings by police

Part 1: Plagued by delays

Part 2: A mother’s anguish

Part 3: On the witness stand

Coming soon: Part 4: Case closed

That scenario has played out 29 times in Manitoba since 2003, with Winnipeg Police Service responsible for 21 deaths, RCMP for seven and the Manitoba First Nations Police Service for one.

The number of fatal shootings involving law enforcement, both in Manitoba and across Canada, has increased in recent years.

The trend has intensified public scrutiny of police conduct and raises questions about whether mandatory inquests are achieving their goal of exploring ways to prevent future deaths.

To find out, the Free Press put two decades of inquests examining deadly encounters with a police bullet under the microscope. Part 3 of our four-part series looks at the narrow scope of expert testimony.

Seven years and five months after Lance Muir was killed by a Winnipeg police officer in a narrow West Broadway alley, the inquest into his death finally began.

Thirteen witnesses were called to testify — each a police officer. One took the stand as an expert witness: Const. Colin Anderson, a use-of-force instructor with the Winnipeg Police Service.

Shortly before 9 a.m. on May 9, 2010, two officers found themselves in the alley, with Muir — who had just broken into a home — behind the wheel of a stolen car. Muir accelerated first towards Const. David Macki, before turning on Const. Tyler Lintick. Hemmed in, Lintick fired four times as Muir drove toward him, hitting the 42-year-old through the car’s windshield.

The whole incident played out in a matter of 28 seconds.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Lance Muir was killed when he drove a stolen car at two police officers in a narrow alley.

At the inquest, Anderson was questioned by the Crown attorney running the proceeding and the Winnipeg police’s longtime lawyer about the tactics the officers had used, as well as the service’s use-of-force policies and training.

Muir’s mother, Lora Schultz, also had a chance to cross-examine the expert.

Schultz, who did not have a lawyer representing her, had just one question: “If he had shot the car, the tires or whatever, would that have made any difference?”

“Based on my training, it wouldn’t have,” Anderson replied, according to a transcript of his testimony.

“Why we’re taught to fire, is to shoot to stop the threat.”–Const. Colin Anderson

“Why we’re taught to fire, is to shoot to stop the threat … And so that means shooting at — if it’s a person — aiming at the centre mass of their body. The intention is not to kill.”

“So, in this situation with Const. Lintick,” he continued, “the threat itself was the way the vehicle was being operated towards him, so he was shooting to stop the threat.”

And shooting at a car’s tire was not going to stop its forward momentum, the instructor added.

“OK,” Schultz replied. Her turn was over.

Next up was Kimberly Carswell, the lawyer for the Winnipeg police. By that point, in 2017, she’d represented the service in at least a dozen other inquests.

“In analyzing this incident and going through it both in paper and here in court, what is your conclusion about the use of force?” Carswell asked.

“That it was reasonable and necessary for the situation,” Anderson responded.

Use-of-force instructors often witnesses

Lance Muir was one of 29 people shot and killed by police in Manitoba over the last two decades. Like Muir, roughly 60 per cent of the victims were Indigenous, according to a Free Press analysis.

Yet lengthy delays in the inquest process — exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic — have meant just 14 inquests have been completed into the 29 deaths. (One completed inquest examined two deaths.)

While the mandatory inquests are prohibited from assigning blame, they do tell a story. A four-month Free Press investigation has found that the story tends to be narrated by police lawyers, police officers and police use-of-force instructors.

It goes like this: police officers in Manitoba, who have the best possible training, encountered people who did not listen, did not comply, did not drop the weapon, leaving officers with no choice but to pull the trigger.

A powerful source of this narrative comes from expert witnesses, who provide their opinions, acting as unbiased helpers for the court.

A police use-of-force instructor has taken the stand in every fatal shooting case where the court heard from an expert witness in the last 20 years. In several of the cases, including Muir’s, the instructor was employed by the same service that shot the victim.

No experts were called in five inquests. In a handful of cases, a pathologist also testified as an expert witness. There’s only been one expert witness who had neither a pathology nor policing background. That witness addressed systemic racism in policing.

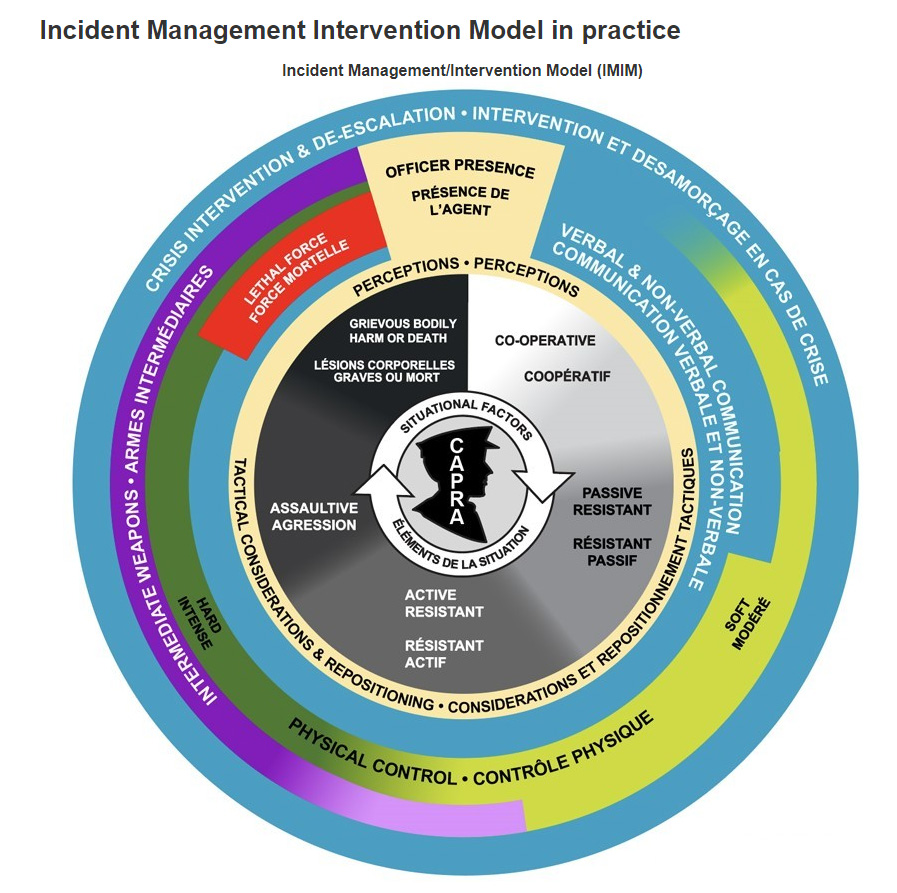

In court, the use-of-force instructors explained jargony concepts like the RCMP’s “Incident Management Intervention Model” or the Winnipeg Police Service’s “one-plus-one doctrine.”

And they made determinations about whether a victim was shot in accordance with a service’s policies and training. In each case, they affirmed the officers’ decision to use lethal force.

In a few cases, experts raised instances where an officer could have improved their tactics, though did not question the ultimate decision to fire.

Focus on moment gun is fired

Determining whether an officer was justified in firing a fatal gunshot is a legitimate line of inquiry at an inquest, said Emma Cunliffe. But it’s far from the only question that needs to be asked.

However, inquests in Manitoba appear to be focused on the “very fine moment” that a gun was fired, said Cunliffe, a professor in the Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia who studies expert witness testimony.

And Manitoba’s heavy reliance on police officers as expert witnesses plays into that, Cunliffe said, reducing an inquest to a single question — was the officer’s decision reasonable?

“In a sense, the problem lies less with the experts — although certainly there’s an issue with only calling those sorts of experts in these cases — than it does with the decisions that have been made about how these cases should be framed,” Cunliffe said.

To consider if anything can be done to prevent similar deaths in the future, which is one of the stated goals of inquests in Manitoba, is “clearly a broader question than that,” she said.

SUPPLIED Emma Cunliffe: broader questions not examined

“It’s an invitation to engage with systemic issues,” she added, noting that those could include an assessment of the adequacy of mental-health services in the province or whether police should always be considered appropriate first-responders.

Ahead of an interview with the Free Press, Cunliffe reviewed four inquest reports and nearly 300 pages of testimony from two: Muir’s and Paul Duck’s. She also drew on her role as the director of research and policy for the Mass Casualty Commission, which examined the 2020 mass shooting in rural Nova Scotia as well as broader issues in Canadian policing, including use of force.

Duck, a 52-year-old Swampy Cree man, was killed by RCMP Const. Shawn Steele in God’s Lake First Nation in 2011 as he walked toward two RCMP officers while carrying a shotgun.

A few minutes earlier, Duck had fired the shotgun into the air to scatter a group breaking into his sister’s house, located in the fly-in community about 1,000 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg.

At the 2015 inquest, RCMP Sgt. Robert Bell, who was then responsible for overseeing the RCMP’s use-of-force program across Manitoba, was an expert witness.

He called the lethal force used against Duck “consistent with training and RCMP policy and legislation.”

Asked if he had any recommendations to improve that training, Bell said he couldn’t think of anything. Judge Murray Thompson ultimately made no recommendations.

Bell also told the court, in extensive detail, about his 19 years with the RCMP, including in general-duty policing in Leaf Rapids, Shoal Lake and Minnedosa; instructing cadets at the training depot in Regina on use of force and firearms; and as a watch commander in Selkirk.

Cunliffe said Bell’s professional background means he could give “expert and impartial evidence” about what the RCMP does to train its cadets, what continuing training it offers police working in the field, or what might happen if an officer fails that training.

A use-of-force instructor from the same service implicated in a case — as in the Duck and Muir inquests — could even testify about whether an officer followed their training, she added.

“But what they can’t do is testify about whether that training is adequate,” she said.

As for Bell specifically, Cunliffe said she saw no evidence to conclude he could testify “authoritatively to the adequacy of the RCMP’s training or to whether it’s consistent with best practices internationally, or with, for example, the insights that might be given by academics.”

“But what they can’t do is testify about whether that training is adequate.”–Emma Cunliffe

Cunliffe also flagged a similar issue in WPS Const. Anderson’s testimony when he took the stand as the only expert in the Muir inquest.

During his testimony, Anderson went largely unchallenged by the inquest counsel, before being guided to certain key points by the WPS lawyer.

Carswell, the police lawyer, asked Anderson about the service’s “use-of-force continuum,” referring to the model that guides the level of force Winnipeg officers should use in different scenarios.

The model is based on a “number of things,” the lawyer said. “Experience, obviously,”

“Yes,” Anderson replied.

“Scientific study and research,” Carswell continued.

“Yes.”

“By independent agencies?”

“Yes.”

“And those studies provide you with information on things that happen to an officer psychologically and physiologically in an incident?” Carswell asked.

“That’s correct,” Anderson said.

To Cunliffe, the interaction was a clear example of an expert who’s testifying outside the scope of their qualification.

“That should be a huge red flag for courts, when you have a use-of-force expert — whose training is limited to the training they’ve received from the service and to the professional experience they have by virtue of being an instructor in use-of-force — claiming that things are based on research,” she said.

When police services make reference to research, it is typically not in an academic sense, she said, but to information gathered and applied — often “unsystematically” — by police.

Earlier this year, for instance, the Mass Casualty Commission criticized the RCMP for its resistance to independent research, as well as its “failure” to embrace a science-based approach to police education.

As Anderson’s testimony progressed about the use-of-force continuum, the inquest counsel — Crown attorney Jay Funke — objected, pointing to the vagueness of the research being cited. Carswell said she did not have the research in front of her.

“I was speaking generally about the fact that the policy isn’t developed by three officers sitting in a back room,” the police lawyer said.

“That should be a huge red flag for courts, when you have a use-of-force expert… claiming that things are based on research.”–Emma Cunliffe

Winnipeg police declined a request to interview Chief Danny Smyth for this series, instead providing written answers to about half of the questions the Free Press submitted. Among the questions not answered was a request for the research referenced by Anderson and Carswell.

Asked about concerns related to Anderson’s testimony, the service said: “The Crown decides who is to be called as witnesses in an Inquest, (and) the presiding Judge, as in all matters before them, decides whether the witness is qualified to testify.”

And those steps were followed in the Muir inquest, the service added.

In her report into Muir’s death, Judge Cynthia Devine noted Anderson did not identify any deficiencies with his service’s training or use-of-force policies. She opted to make no recommendations.

“Judges aren’t meant to play the role of a rubber stamp.”–Brandon Trask

Brandon Trask, an assistant professor of law at the University of Manitoba who specializes in criminal law and evidence, said the Fatality Inquiries Act — which governs inquests in Manitoba — allows for some relaxation in how evidence is presented. But this shouldn’t mean the rules get thrown out, he said.

“If someone were to take this relaxation of rules of evidence to extremes, then the process would risk turning into a free-for-all, with people just expressing opinions and hoping that the court essentially latches onto one perspective,” he said, speaking generally, and not about a particular case.

Failing to uphold standards of evidence in an inquest could lead to less helpful recommendations, Trask said, noting it is up to the judge to assess expert testimony and decide how much weight to give it.

“Judges aren’t meant to play the role of a rubber stamp,” he said.

Resistance to changing use-of-force models

Judith Andersen is an associate professor in the department of psychology at the University of Toronto who researches how to train police officers to make better use-of-force decisions.

She has studied the issue in both North America and Europe, in particular, with the Police University College in Finland, and has spent hundreds of hours watching use-of-force training. The conclusion she’s drawn is that while not every shooting can be prevented, the rate can be reduced with research-based training and policies.

“My research has specialized in showing that officers have physiological stress reactivity to those high-threat situations and acute stress. And that’s related to making lethal-force errors,” said Andersen, who served on the research advisory board for the Mass Casualty Commission.

“It’s not a question of if they’re having stress reactivity that results in errors in decision-making and the use of force, it is a matter of what do we do about it? And the current policies do not speak to that, they do not train to that,” she added.

ANDREW VAUGHAN / THE CANADIAN PRESS Judith Andersen says use-of-force models in Canada tend to emphasize escalation, not de-escalation.

Andersen said the use-of-force models typically employed need to be reinvented since they tend to emphasize escalation.

In 2018, she and other researchers created a “decision model” as an alternative. The model, which focuses on de-escalation and having officers recognize their internal stress levels, was published in a peer-reviewed journal article assessing different police responses to people experiencing mental-health crises.

But, Andersen noted, there is strong resistance in Canada to changing existing models.

The researchers’ model also makes it clear using lethal force is a “last resort” — a message Andersen said is strenuously enforced in Finland.

The training and mindset in Finland, she said, is that all calls “will be de-escalated non-violently and safely — even if the person does have a knife or a gun.”

Between 2000 and 2018, Finnish police fatally shot eight people in the country of around 5.5 million people, according to Yle News, a branch of Finland’s public broadcaster.

“We’re giving life or death tools and options — weapons — to people who have very limited training.”–Judith Andersen

As for training, it needs to be overhauled, not just tinkered with, Andersen said, noting existing “scenario-based training” — which involves actors or other officers acting out short examples of confrontations — tends to emphasize the need to use force.

It also comes down to time, she said. In Finland, basic police training takes three years. RCMP cadets, by comparison, undergo about six months of pre-employment training followed by on-the-job instruction. In Winnipeg, police training runs for nine months.

“Think of it from a model of training surgeons. Nobody would give them a knife and say go into cardiovascular surgery. You could kill somebody,” she said.

“And yet, we’re giving life or death tools and options — weapons — to people who have very limited training.”

‘Disappointing’ revisions to RCMP use-of-force model

At the 2015 inquest into Paul Duck’s death, Sgt. Bell raised changes that had been made to the RCMP’s use-of-force model in 2009, according to a transcript of his testimony.

Two underpinning principles were removed — that “the best strategy for police officers was to use the least amount of intervention possible” and “the best intervention caused the least amount of harm,” Bell testified, noting he was paraphrasing.

“There was nothing in the legislation or case law that supported either of those underlying principles,” he added.

Andersen, the psychology professor, called the RCMP’s decision “disappointing” but not surprising.

“They’d rather remove than actually address it,” she said.

Asked why the RCMP has eliminated its principle to use the least amount of force, Simon Baldwin, the manager of the RCMP’s Operational Research Unit, said in an interview it was not “a realistic threshold.”

Baldwin, who has a PhD in psychology from Carleton University, said situations can be escalated if officers are required to use the least amount of force — rather than the “right amount of force at the onset.”

RCMP Sgt. Nick Widdershoven, a senior policy analyst with the National Police Intervention Unit, who’s been designated as an expert in use of force by the service, added one of the primary principles of police officers is to “preserve and protect life.” This includes both the lives of the public, as well as officers, he said. Baldwin and Widdershoven were jointly interviewed by the Free Press in early August.

“We don’t have the intention to cause harm, we have intention to resolve situations in the best way we can,” Widdershoven said.

Widdershoven also said the RCMP revised its visual use-of-force model in 2021 to put more emphasis on crisis intervention and de-escalation. (The updated graphic is virtually identical to the previous iteration, except that now the words “crisis intervention & de-escalation” encircle it.)

“(This reflects) the fact that we’re at a 99.9 per cent interaction with the public that doesn’t result in any reportable use of force,” Widdershoven said.

“We don’t have the intention to cause harm, we have intention to resolve situations in the best way we can.”–RCMP Sgt. Nick Widdershoven

At the inquest into Duck’s death, Bell was questioned by Martin Pollock, one of the lawyers for the victim’s family. The lawyer pressed Bell on whether the officer who shot Duck could have continued to give commands for a few seconds longer than he had.

Bell said it may not have been possible. He explained RCMP cadets are taught “the average gunfight lasts 2.5 seconds.” And based on that, five seconds of dialogue would present an issue, he said.

The notion was recently backed by RCMP spokesperson Robin Percival. She wrote in an email that “use of force incidents occur in seconds, and in some cases, fractions of seconds” and cited two studies. One study, published in the Journal of Forensic Biomechanics, found the average time for a potential assailant to shoot an officer was 1.13 seconds, she noted.

That study was funded by the Minnesota-based company Force Science Ltd., which is led by police psychologist William Lewinski. A former Minnesota State University professor, Lewinski is controversial for his voluminous expert testimony across the U.S., defending the actions of officers who shot citizens in “questionable circumstances,” according to a New York Times investigation. His police training urges officers not to delay when making lethal-force decisions.

Lewinski co-authored both studies the RCMP cited.

One-plus-one: police respond with higher force

Winnipeg police’s use-of-force policy includes a concept known as “one-plus-one doctrine.” Instead of responding with the same level of force as a combative or resistant member of the public, according to the doctrine, officers have the option to respond with one level higher of force.

An officer must “be able to articulate that they did not have the skill, or time, to safely engage and control a person using equal force,” states a version of the WPS policy, which was filed as an exhibit in a 2019 inquest into two fatal shootings.

In its written statement, Winnipeg police noted the doctrine is an option, not a requirement.

“WPS Use of Force policy has been examined by the Court in many of the Inquests as well as reviewed by experts in use of force. The policy has been determined to be appropriate and in line with Canadian police standards,” the service’s statement continued.

One of those experts was RCMP Sgt. Robert Bell.

“The policy has been determined to be appropriate and in line with Canadian police standards.”–Winnipeg Police Service statement

In 2016, a year and a half after his testimony in the Duck inquest, Bell was called as an expert witness into the fatal shooting of 26-year-old Craig McDougall by Winnipeg Patrol Sgt. Curtis Beyak.

McDougall, who was from Wasagamack First Nation, was shot in 2008 while holding a knife and advancing on several officers, outside a West End home where he lived with his father.

Bell also provided the inquest with a written report, a copy of which was viewed by the Free Press. In his report, Bell seemed to carefully critique Winnipeg’s one-plus-one doctrine.

“This is the one area of WPS use of force policy that I would consider to be somewhat inconsistent with the philosophy behind the NUFF,” the sergeant wrote, referring to the National Use of Force Framework, a guiding approach initiated in the late 1990s by the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police.

The latter framework, he’d noted, “does not make provisions for an officer to specifically utilize a level of intervention (or control) that is higher than the identified behaviour.”

Bell said, however, the differences between the two frameworks were “minor.” He concluded the actions of the Winnipeg officers involved in McDougall’s death were “consistent with law, WPS policy and best practices in tactical training available at the time of the incident.”

His language closely mirrored the wording he’d used when testifying at the Duck inquest.

‘Uneven’ access to expert witnesses

When it comes to the testimony of expert witnesses, it should be a question of fairness. In reality, it isn’t.

Martin Pollock, the lawyer who represented the Duck family, along with his late father, Harvey Pollock, said the “playing field is uneven” as families face an uphill battle obtaining their own expert.

Pollock is currently representing the family of 22-year-old Stewart Andrews, who, like Duck, was from God’s Lake First Nation. Andrews was killed by a Winnipeg police officer in 2020.

“I represent people who are disenfranchised. I represent people who do not have funds to hire experts,” Pollock said, speaking generally, and not about a particular case.

“Of course, when you have the police, there’s a financial machinery, which they avail themselves (of).”

Pollock argued a pool of funds should be set aside for judges to allot — to enable families to hire a particular expert.

Craig McDougall inquest

The inquest into the death of 26-year-old Craig McDougall was unusual in a few ways.

For one, four expert witnesses testified.

Among them was Jonathan Rudin, then the program director at Aboriginal Legal Services, who wrote a report ahead of the inquest — then testified — about the possible role of systemic racism in McDougall’s death.

The inquest into the death of 26-year-old Craig McDougall was unusual in a few ways.

For one, four expert witnesses testified.

Among them was Jonathan Rudin, then the program director at Aboriginal Legal Services, who wrote a report ahead of the inquest — then testified — about the possible role of systemic racism in McDougall’s death.

In his 2016 report, Rudin wrote that with the information available to him, it would be difficult to determine whether systemic discrimination played any role in McDougall being shot.

Rudin did, however, raise serious concerns about how McDougall’s family was treated immediately afterward, referencing the handcuffing of his father, uncle and father’s girlfriend.

“That Aboriginal people are thrown to the ground and handcuffed following a shooting seemed, in some way, appropriate (or at least not inappropriate) to all the officers involved,” Rudin wrote.

“It is easy to see how those individuals might conclude that they were treated the way they were because they were Aboriginal people,” he added.

“It appears, certainly on the surface, to be the only possible explanation for their treatment.”

Inquest judge: Anne Krahn

Time from Craig’s death to the inquest report’s release: eight years, nine months and 10 days

Expert witnesses:

- Jonathan Rudin;

- RCMP Sgt. Robert Bell;

- Michael Brave, litigation counsel with TASER International, Inc. and a law enforcement officer;

- Howard Williams, lecturer at Texas State University and former police chief of the San Marcos Police Department.

Number of recommendations made: 16

This dynamic unfolded in the inquest into McDougall’s death. His father, Brian McDougall, and lawyer Corey Shefman argued for the judge to expand the inquest’s scope to examine the role structural racism may have played in the shooting — and to that end, to have an expert testify on the topic.

Both inquest counsel and Carswell, the Winnipeg police lawyer, argued there was “no factual basis for a claim of racism” because the entire incident took less than 100 seconds.

“Ms. Carswell argued that if the evidence established racism of any type, we would not miss it,” Judge Anne Krahn wrote in her decision.

“I am not so sure. It is a matter of perspective. And I accept that systemic racism is subtle, sometimes hidden and not obvious.”

Ultimately, Krahn approved the request, which opened the door for Jonathan Rudin, then the program director at Aboriginal Legal Services in Toronto, to take the stand.

“We had to fight every single step of the way to get the court to let Jonathan Rudin testify, yet the police’s own use-of-force experts got to testify automatically,” Shefman wrote in an email.

Yet examining the “social and cultural causes and consequences” of Craig’s death was critical, Shefman said, both in understanding what had happened, as well as in making recommendations.

An unnamed provincial spokesperson refused the Free Press’s request to interview an official with the Manitoba Prosecution Service about its inquest procedures, and instead provided written responses.

“If a party other than inquest counsel seeks to have an area examined/evidence presented, that would be discussed with the judge who would make the ultimate decision,” the spokesperson said, adding “nothing precludes” a party with standing from applying to present their own expert.

When asked about the narrow range of the expert witnesses, the spokesperson replied: “In inquests that examine police conduct, normally experts are called who come from a law enforcement background.”

Breaking that pattern proves difficult.

Sen. Kim Pate was previously the executive director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies. She has appeared as an expert witness in a number of inquests but was blocked from testifying in one, when a Saskatchewan judge questioned her ability to be independent “in light of her three-and-a-half-decade-old advocacy role.”

“The test of objectivity, or ability to provide helpful advice, favours those who already work within the system — over those who may work at trying to change or challenge the system,” Pate told the Free Press.

Yet, she added, judges should “not accept, without question, testimony that comes from police or correctional authorities — when it is their behaviour being examined.”

Lack of confidence in inquest system

More than 30 years ago, the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry examined the treatment of Indigenous people by police and courts in Manitoba, after John Joseph “J.J.” Harper, a 37-year-old man from Wasagamack First Nation and the executive director of the Island Lake Tribal Council, was killed on a Winnipeg street by Const. Robert Cross. (Harper was Craig McDougall’s uncle.)

In their final report, inquiry commissioners Alvin Hamilton and Murray Sinclair issued a clear warning about the inadequacy of the province’s inquest system.

“(Without changes), there is every reason to believe this kind of ordeal — a complete lack of confidence in inquest procedures by members of the deceased’s family and the affected community, and a resulting sense of injustice and alienation, with subsequent demands for a public inquiry to clear up the problem — will happen again,” the commissioners wrote.

The commissioners made eight recommendations to strengthen the inquest process, but few have been implemented.

Today, their prediction is prophetic.

In April 2020, a Winnipeg police officer shot Eishia Hudson, a 16- year-old girl from Berens River First Nation, through the window of the stolen Jeep she was driving. It followed a robbery from a liquor store and a car chase.

About nine months later, the Independent Investigation Unit of Manitoba — which investigates “serious incidents” involving police — later determined no charges were warranted. The officer, who has yet to be named, declined to be interviewed by the IIU.

At a 2021 press conference responding to the lack of charges, Eishia’s parents — William Hudson and Christie Zebrasky — called for a public inquiry into police use of force against Indigenous people in Manitoba. While an inquest into Eishia’s death is mandatory, a public inquiry can only be called by the premier and is meant to be a broader examination of issues.

“It was whitewashed, (it was) very, very racist towards all Indigenous peoples. It was bullshit, that’s what it was,” William Hudson told the media.

“When a young officer that just came on the force could get away with something like this? What does that show for our people?”

WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Eishia’s parents, William Hudson and Christie Zebrasky, have called for a public inquiry into police use of force against Indigenous people. While an inquest is mandatory, an inquiry can only be called by the premier.

Danielle Morrison, an associate lawyer at Cochrane Saxberg, is one of the lawyers representing Eishia’s family, both in the inquest and a civil lawsuit.

Morrison, who is from Anishinaabeg of Naongashiing in Treaty 3 territory, said in an interview that the circumstances for Indigenous people in Manitoba have become worse — not better — since the AJI concluded decades ago.

“You just hear so much about police brutality in our communities, that doesn’t make the news because it happens so often — where people are afraid to speak out,” she said.

After Eishia was killed, the need for a public inquiry was immediately apparent, she said.

“What the family hopes for is that a public inquiry will follow up on what the AJI started,” Morrison said.

“There has to be some report card on whether any meaningful progress has been made with the justice system and how it treats Indigenous people.”

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Danielle Morrison, one of the lawyers representing Eishia Hudson’s family, says inquests need to examine the role systemic racism may have played in shootings.

In the meantime, Morrison and the rest of the legal team for Eishia’s family are pushing to expand the scope of the inquest to allow for an examination of whether systemic racism contributed to the teen’s death. The team is set to make a motion in October.

But the notion that racism is beyond the scope of an inquest — and must be argued to be included — is frustrating for Morrison.

The purpose of an inquest, she pointed out, is to find out as much as possible about what contributed to a community member’s death.

“If something like systemic racism contributed to that, then we need to go down that avenue.”

The Free Press is interested in hearing about your experiences with the inquest system. If you have something you’d like to share, please contact us at marsha.mcleod@freepress.mb.ca

Marsha McLeod

Investigative reporter

Signal

Marsha is an investigative reporter. She joined the Free Press in 2023.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.