Rural Manitoba lacking mental-health services for youth

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/10/2023 (734 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

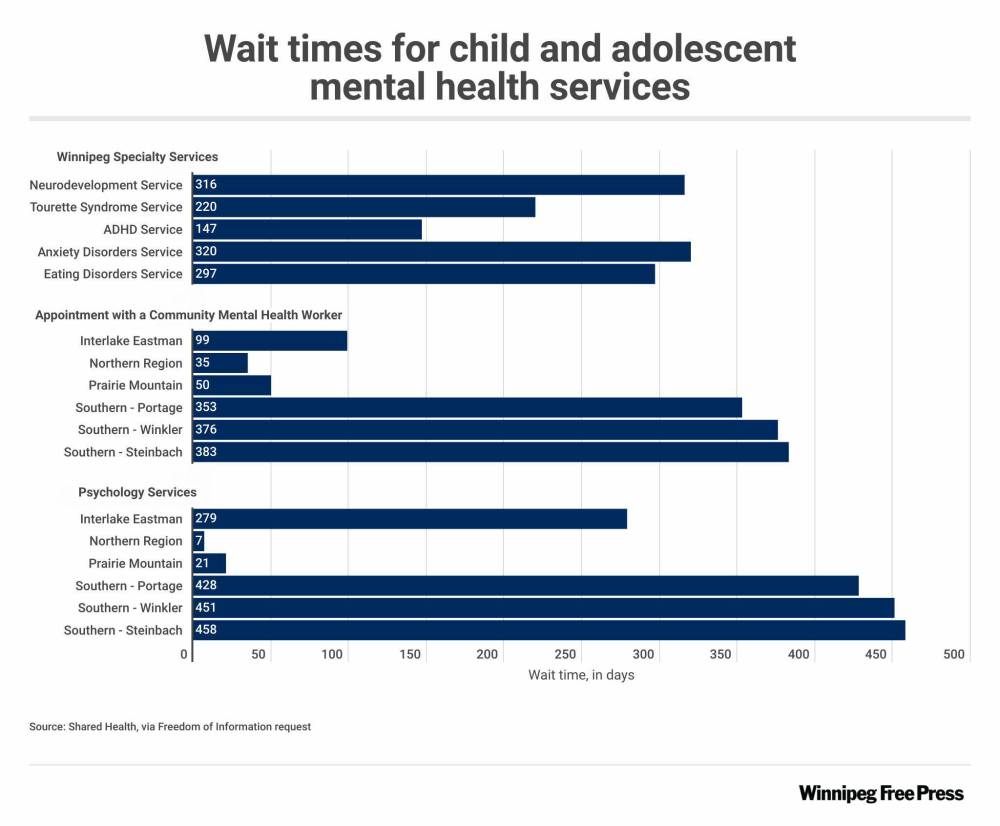

Youth in rural Manitoba are lingering more than a year for access to mental-health care, as wait times continue to grow for psychology and community appointments.

The wait for the province’s publicly funded Psychology Services program is more than 400 days for youth in Portage la Prairie, Winkler and Steinbach, recent data show.

Where individuals live plays a big part in the ability to access timely care. Getting an appointment with a community mental-health worker takes 35 days in the Northern Health region, 50 days in the Prairie Mountain (which includes Brandon) and 383 days in Steinbach.

Specialty child and adolescent mental-health services in Winnipeg all have wait-lists several months to more than a year long. (The WRHA’s ADHD service has the shortest wait list, at 147 days. The 316- and 320-day respective wait lists for the child and adolescent neurodevelopment and anxiety disorders services are the highest.)

The figures were collected this summer via a freedom of information request and provided to the Free Press by advocates working on the Disability Matters Vote campaign.

Members had voiced concern about long waits for services that had ballooned during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The statistics reflect what Kirsten Drybrough hears from families who are trying to get their children mental-health appointments.

Drybrough, a family peer support worker and co-founder of local non-profit All in Family, said some of the clients she works with have reported waiting upwards of a year to get a brief psychiatric appointment, even when that young person is considered to be in crisis and experiencing suicidal thoughts.

“That just doesn’t even make sense. It lacks compassion and logic, in my opinion, but sadly, the wait times are disgusting,” Drybrough said Monday.

During its three years in operation, the peer-support non-profit has assisted about 1,500 families while they wait for mental-health care.

The long waits are causing harm and signs of post-traumatic stress disorder in caregivers, Drybrough said.

“It just takes its toll on everyone’s well-being, both their physical and mental health of everybody in that home, and the services to support family members are absolutely non-existent in our traditional setting of our mental-health systems for youth,” she said.

All in Family runs a support group and relies on donations.

A mother in the Interlake-Eastern health region said her two-year fight to get proper mental-health care for her young teens involved a near-two-year wait for a youth psychological assessment, repeated trips to the Children’s Hospital ER in Winnipeg, and turning to private providers.

Along the way, she said doctors suggested the process could be sped up if the family was involved with Child and Family Services or even the criminal justice system. The mother spoke on the condition of anonymity because her family lives in a small community and did turn to CFS for help after her child showed severe mental-health symptoms and “unmanageable violent behaviour.”

“We had to work very hard to try to disentangle ourselves (from CFS), and we still are. This is not finished,” she said.

The woman said her family found out first-hand about the disparity accessing services depending on where you are physically located outside of Winnipeg.

The stress on her family “is horrific,” she said. “You can’t sleep, you don’t know, ‘Do I have to drive to Winnipeg at 4 a.m. in a blizzard’ (to get emergency treatment) — and the stress doesn’t go away.”

Manitoba needs dedicated mental-health facilities for youth outside of Winnipeg who are in crisis, and more streamlined navigation of the existing system, she said.

“There’s zero support for the patient and family. Everything that we have found, we have found through fighting and digging, requesting documentation, countless hours of phone calls trying to find places doing intake.”

katie.may@winnipegfreepress.com

Katie May is a multimedia producer for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.