The art of war Prints of paintings by some of Canada’s most acclaimed artists were shipped to Second World War troops to lift their spirits and provide physical reminders of what they were fighting for

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/11/2023 (763 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Canada’s artists didn’t leap from landing craft onto Juno Beach nor did they incur heavy casualties at Ortona or on supply ships during the Battle of the Atlantic.

Like many Canadians who were not on the front lines during the Second World War though, artists found ways to do their part in the war effort that went beyond purchasing Victory Bonds or rationing sugar and flour.

One such plan that almost faded away in eight decades of history is getting a revival this month in Winnipeg.

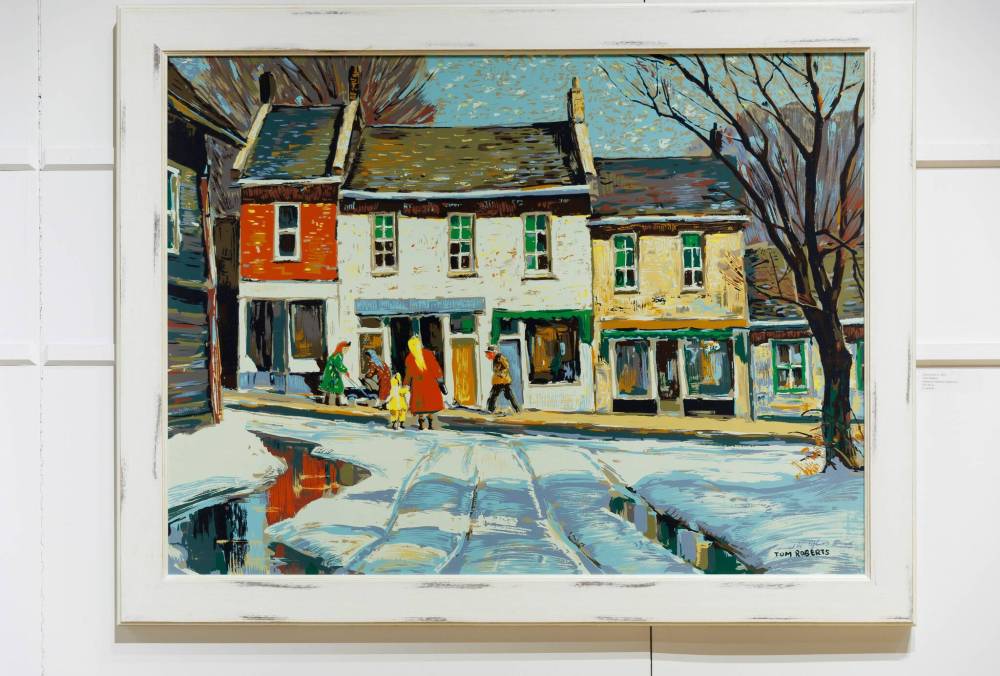

The Sampson-Matthews Print Program brought oil-silkscreen pictures of Canada to army barracks, air-force bases, mess halls and training camps in Canada and Europe to remind servicemen and women of home.

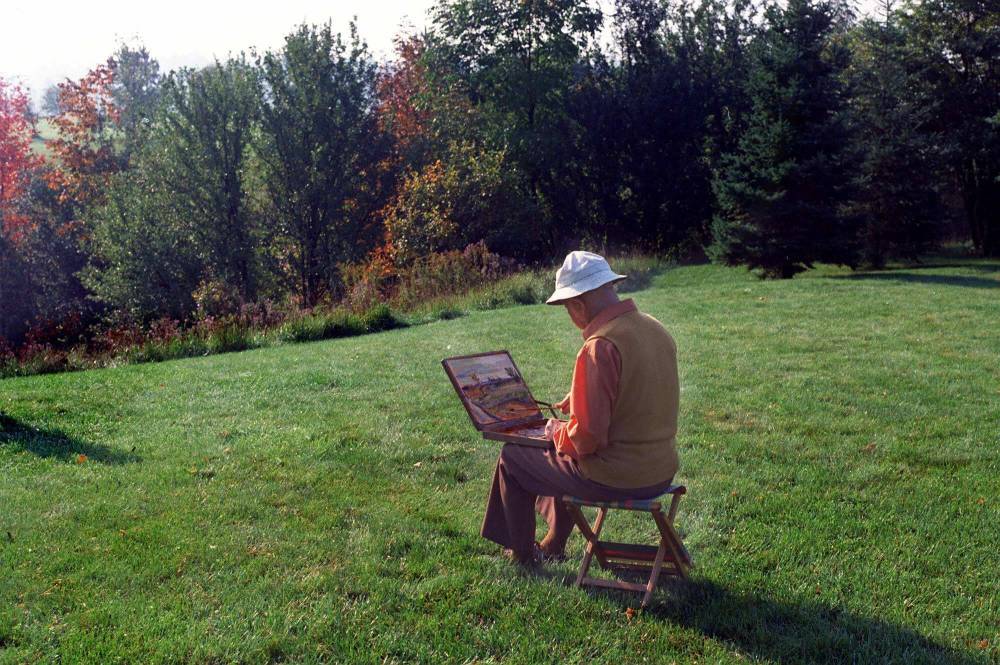

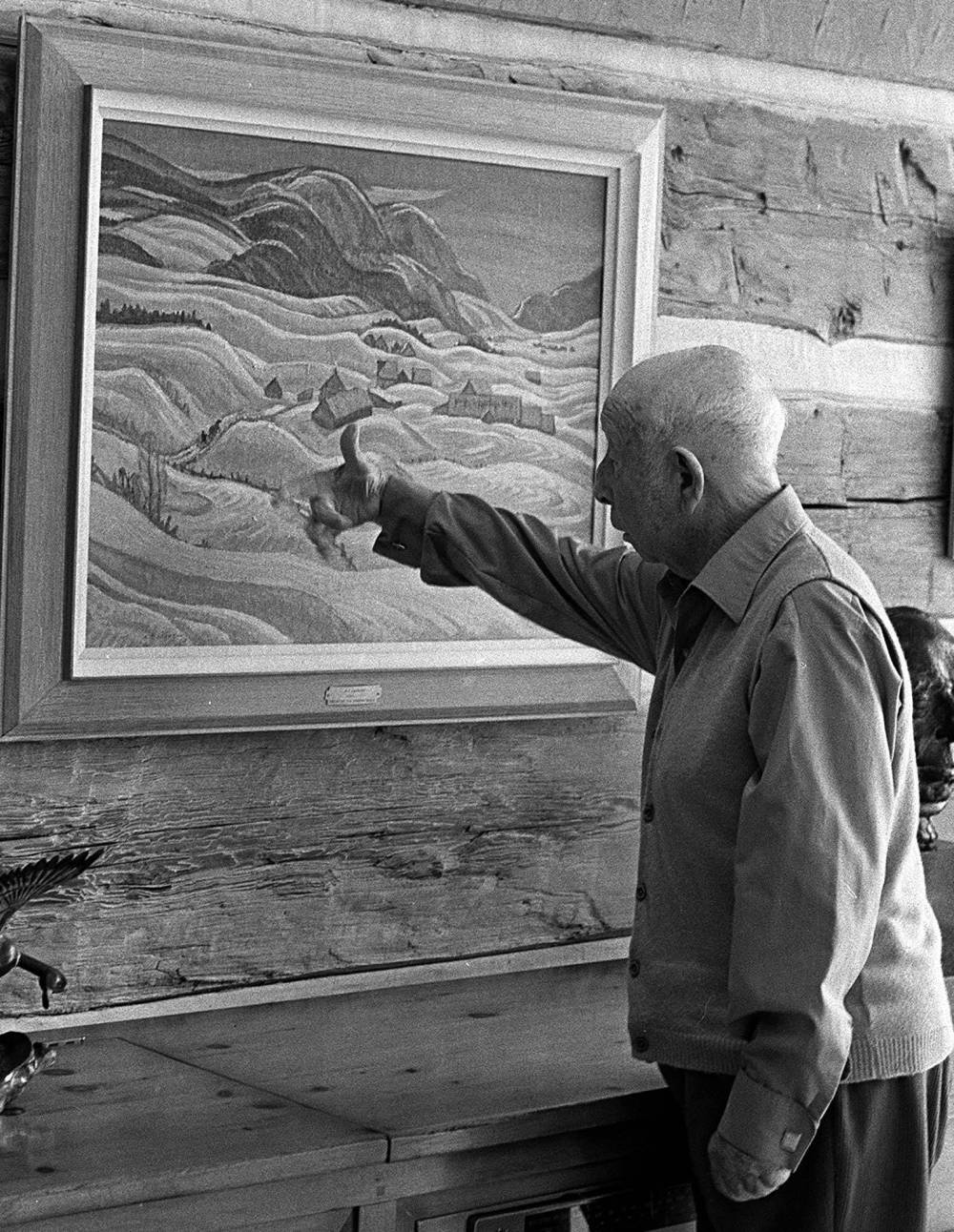

A.Y. Jackson, a founding member of the Group of Seven Canadian landscape painters who also created some of the most striking paintings from Flanders during the First World War, likened it to a New Deal-style jobs program for Canada’s struggling artists in the 1930s and ’40s.

“If we can get twenty or thirty typical examples of Canadian art scattered through all the camps in Canada we will have accomplished a lot — cheered up the camps and made the boys familiar with our work for the first time in their lives,” he writes in a letter to Harry McCurry, the director of the National Gallery of Canada at the time, which is cited in the 2015 book Art for War and Peace: How a Great Art Project Helped Canada Discover Itself by Ian Sigvaldason and Scott Steedman.

The print program went far beyond Jackson’s imagination. It would become Canada’s largest public-art project and a post-war symbol of a country building a new identity forged by millions of Canadian soldiers, sailors, air crews and medical personnel during the war.

”(Jackson) remembered how dismal the armed forces barracks were and how there was really nothing Canadian,” says Bill Mayberry, president of Mayberry Fine Art, which is hosting Art for War and Peace, an exhibition of 25 of the Sampson-Matthews Print Program works at its McDermot Avenue location until Nov. 24.

“It was so successful, they toured full sets throughout Europe… Europeans had never seen anything like this. There had no exposure to Canadian art to speak of at all.”

Silkscreened prints using oil paint were made between 1942 and 1963 at Sampson-Matthews’ printmaking company in Toronto, which before the war made posters, billboards and other advertising material.

Jackson was put in charge of selecting the initial 36 paintings to be screened, some of which were from the National Gallery of Canada’s permanent collection.

A.J. Casson, a fellow Group of Seven artist who was a silkscreening expert with Sampson-Matthews, supervised the screenings, which was a painstaking process that likely took more time than it did to paint the originals, and certainly more faithful to the originals than digital re-creations made in the 21st century with laser printers.

“You couldn’t even begin to think about doing a project like this today,” Mayberry says. “There was between 10 to 20 screens into making every print, and those screens would have to be constantly remade because the pigment would always gum them up.

“They had a team of people constantly remaking the screens.”

The program continued after the war and the prints became commonplace in government departments, embassies, post offices, schools and libraries.

Eaton’s sold them for $5 each at one point — $4 for schools, Mayberry says — so they became “art for the common man,” Ian Sigvaldason and Scott Steedman write in Art for War and Peace, from which the Mayberry exhibition takes its name.

The pictures became so ubiquitous in government offices and ambassadors’ residences they were included in a movie set in the Oscar-winning film Argo, a fictionalized account of the 1979 rescue of six Americans from Iran led by the Canadian embassy in Tehran and ambassador Ken Taylor.

Tens of thousands of the prints were made during the war, and many more thousands afterward but relatively few remain today, especially those printed during the war years.

Some of the 117 different works are so rare they are rarely seen, let alone exhibited in public. The national gallery has only 99 of them.

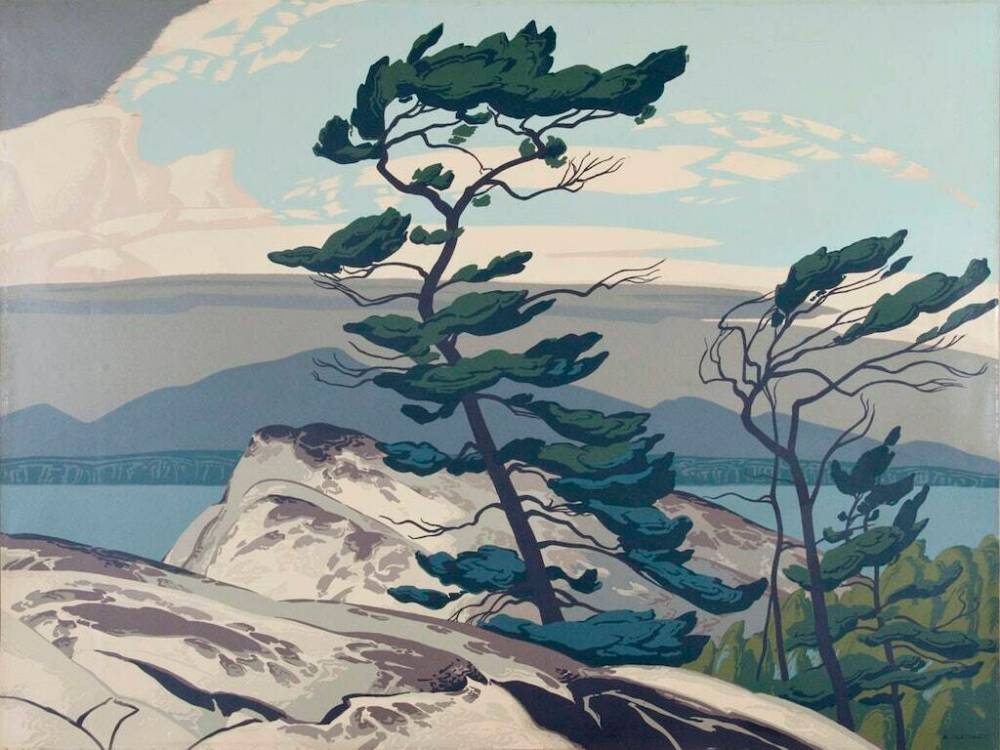

Among the rare ones are Casson’s White Pine, which is one of the highlights of the Mayberry exhibition.

The 1957 original is part of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Vaughn, Ont., but its silkscreen version has become almost as valuable, and is on the cover of Art for War and Peace.

Once the war ended in 1945, army barracks and mess halls were taken down and everything within them — including the prints — became needless rubble.

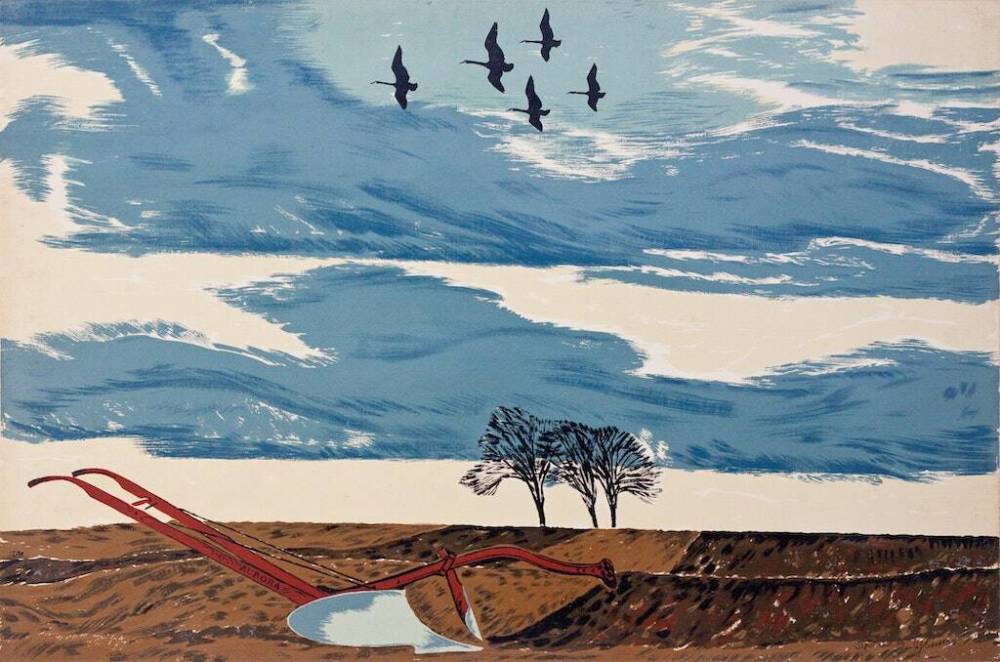

Others in government offices were discarded during renovations, adding to the prints’ rarity and value, which range from about $1,500 for a print of The Plough by Toronto illustrator Thoreau MacDonald to almost $8,000 for Emily Carr’s Indian Church (White Church).

That’s another highlight of the exhibition, and her fame is only part of the reason why it’s the most valuable in the exhibition.

“It was made at the end of the war and as the story goes there were 80 of them produced and 40 of them went overseas and the ship went down,” Mayberry says. “As the story goes.”

Like most collectibles that have become contemporary antiquities, such as sports cards or old children’s toys, the condition of the print plays a large part in its value.

Sampson-Matthews used paperboard for the oil screens, the same material used for shoeboxes, and they are susceptible to moisture damage, which leads to the paint peeling from the paperboard.

People believe prints are less valuable than originals, even if some of the prints in the exhibition are 80 years old.

“If people don’t think something is worth anything, they won’t take care of it,” Mayberry says.

Mayberry Fine Art, which purchased one Sampson Matthews print earlier this year, has sent some of the pictures from the exhibition to professional restorers.

Casson’s choice of using oil paint for the silkscreens has given the works a far longer lifespan than prints made with ink. The vivid colours of those in the exhibition have withstood the test of time, once years of dust had been carefully brushed away.

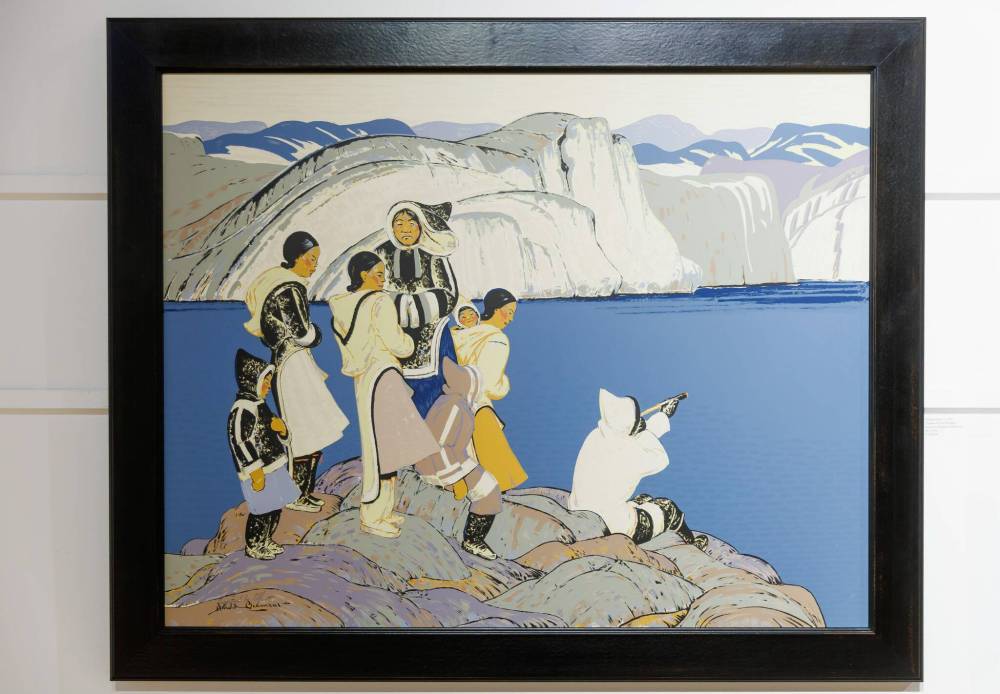

Many of the prints, which are all 76 centimetres by 101 centimetres (30 inches by 40 inches) in size, are scenes from Ontario and Quebec. Jackson, Casson and the National Gallery tried to include ones from across the country, and some are Arctic scenes.

Among the Prairie landscapes is Assiniboia Valley by Frederick H. Brigden, which is of an unnamed town west of Winnipeg, where he had opened a branch of Brigdens Limited, a Toronto-based graphic-arts business.

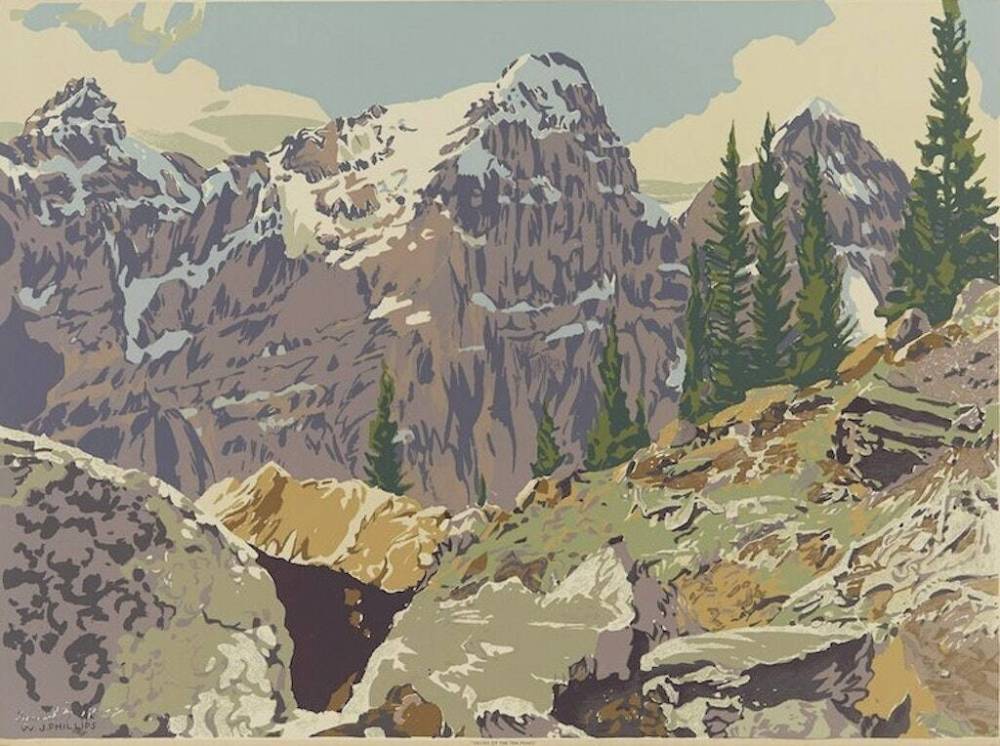

Walter J. Phillips, the Winnipeg artist who created many woodcuts of scenes near Lake of the Woods in the 1910s and ’20s, has two of his works in the Sampson-Matthews collection, and a screen of his Valley of Ten Peaks hangs in the Mayberry show.

It also includes Algoma Country by the Group of Seven’s Lawren Harris, whose paintings have risen in popularity recently after a Toronto art show of his works was curated by actor Steve Martin, an avid collector of Harris’s paintings.

Mayberry has his own history with the prints that took place when he moved to Canada from Northern Ireland in 1970, long before his art business started buying and selling them.

He has dreamed of putting together an exhibition of them that would coincide with Remembrance Day. This year is his year.

“In 1971, I started working for a gallery in Winnipeg as a picture framer, and in the window of this little gallery on Selkirk Avenue were two Sampson-Matthews prints,” he says. “What did I know about art in 1971? I was 21 years old but I was fascinated with them and the memory stayed with me.”

Alan.Small@winnipegfreepress.com X: @AlanDSmall

Alan Small

Reporter

Alan Small was a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the last being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.