Antarctic whaling’s dark history offers hope

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/12/2023 (706 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s a bit of a trend in non-fiction writing these days for an author to weave his or her personal experience into a historical tale, coaxing parallel structures out of seemingly disparate narrative strands.

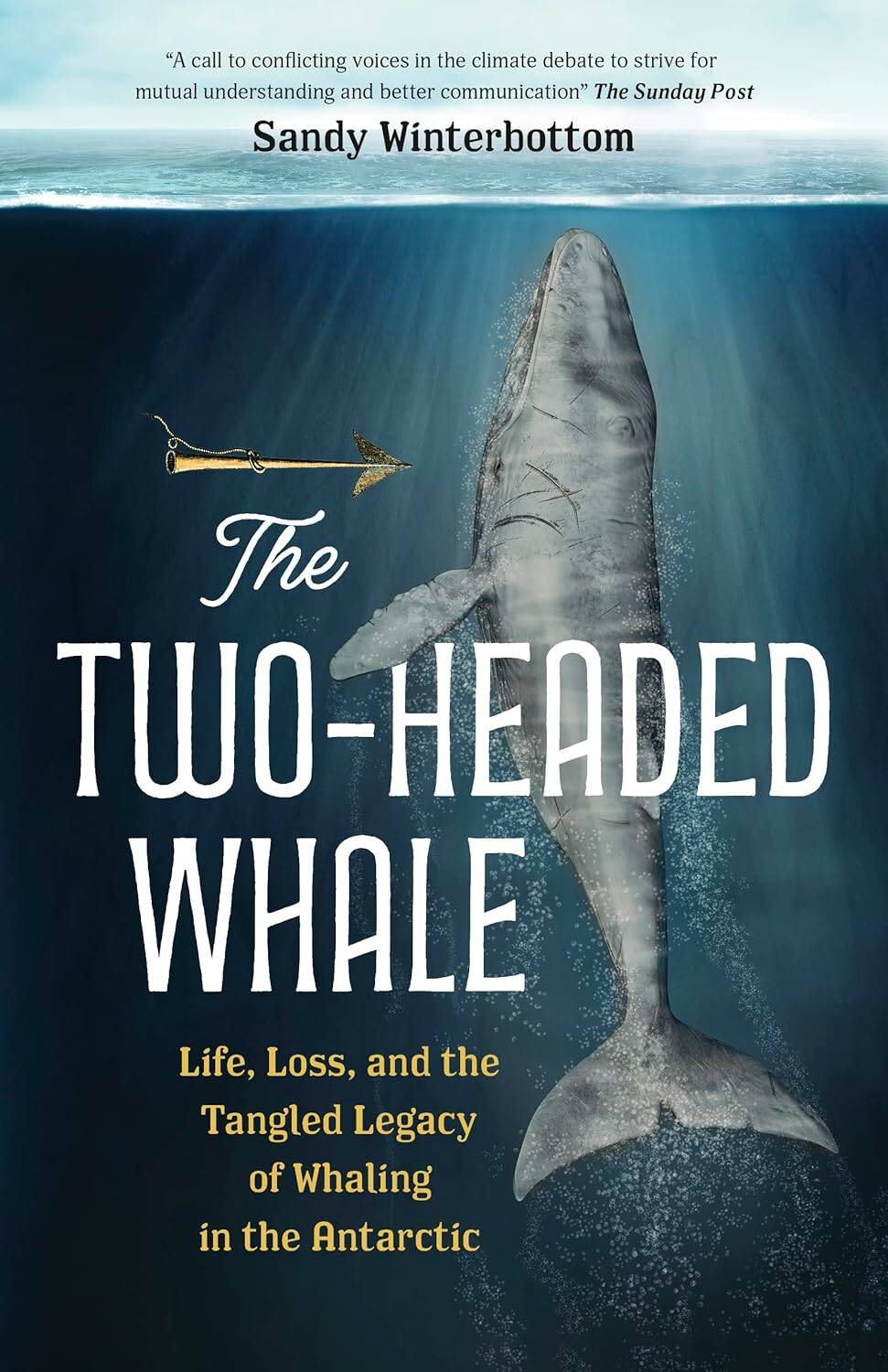

It’s tricky to pull off without veering into navel-gazing or narcissism. At first, Scottish academic Sandy Winterbottom’s debut book, which combines an exploration of the prewar whaling industry with a recounting of her own sailing trip to Antarctica, feels as if it might fall into those traps: it’s a takedown of a barbaric practice that led to the near extinction of a species, twinned with a tenuously connected climate-change polemic, her own struggles with eco-anxiety and her partner’s general anxiety.

But although the chapters detailing Winterbottom’s journey aboard the tall ship Europa sometimes read like a travelogue, larded with too many poetic similes and adjectives, the alternating chapters are downright gripping, a richly detailed, you-are-there recounting of a teenager’s time in the employ of Salvesen’s, a firm out of Scotland that fed the world’s “need” for whale oil and ambergris.

And as The Two-Headed Whale progresses, the author’s braiding of the two narratives results in a remarkably moving and effective story. It humanizes the whale hunters while exposing the vast and ongoing harm they caused, acts as an ode to the brutal and beautiful allure of Antarctica (which draws explorers and exploiters alike) and exposes the roles of colonialism and capitalism in causing environmental damage.

When one thinks of whaling, the era of Moby-Dick springs to mind, but widespread commercial whaling continued well into the 1960s, with crews from the U.K., Norway and Japan competing fiercely on factory ships in the South Atlantic to edge each other out before the staggering yearly quota of blue, fin, humpback and minke whales was caught.

Between 325,000 and 360,000 blue whales were killed in the Southern Ocean in the 20th century; as few as 5,000 remain today.

Despite its incredibly remote location (1,400 kilometres off the coast of the Falkland Islands), South Georgia Island has a storied history. Ernest Shackleton paddled his men 1,300 kilometres in a lifeboat to reach her shores after his ship, the Endeavour, was crushed by pack ice; the British explorer is buried there. (It’s also where the Falkland War technically began.)

This frigid island, populated by an incredibly diverse collection of wildlife, was the seat of the mid-century whaling empire, operated out of whaling stations that resembled frontier towns in the Old West — ramshackle, wild, filthy — with a smell “pungent as chloroform” and a “soup of stinking whale intestines rotting in the bay.”

Anthony Commisky Ford was one of the young men — boys, really — who were lured to the life of whaling by the promise of astronomical wages and adventure on the high seas. His death at age 18 was commemorated only by a simple tombstone on South Georgia. When Winterbottom visits the island in 2016, his youth catches her eye and launches her investigation into his all-too-short life.

Winterbottom’s vivid, touching portrayal of the lad, who joined up in 1952, is somewhat fictionalized. He’s an amalgam character based on her extensive research, including letters from other boys who worked the same gruelling shifts at sea, who experienced the same homesickness, cold, and drudgery, interrupted only by moments of high peril.

They also may have felt the horror of watching hundreds of magnificent creatures flensed, their blubber harvested and hauled into the boilers of the factory ship to be rendered into oil, their innards dumped into the sea.

The Two-Headed Whale is a grim reminder that our actions have long-lived consequences, but Winterbottom does give us some hope that healing can happen, whether it’s in Antarctica or closer to home.

Jill Wilson is the Free Press Arts & Life editor.

Jill Wilson is the editor of the Arts & Life section. A born and bred Winnipegger, she graduated from the University of Winnipeg and worked at Stylus magazine, the Winnipeg Sun and Uptown before joining the Free Press in 2003. Read more about Jill.

Jill oversees the team that publishes news and analysis about art, entertainment and culture in Manitoba. It’s part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.